Ace of Spies (22 page)

The War Cabinet in London, and the Allies collectively, now had two potential choices; they could either make a renewed attempt to entice the Bolsheviks back into the war against Germany, or

they could intervene in Russia in the hope that the Bolsheviks could be toppled in favour of a pro-war government. Either way, the need for good intelligence sources in Russia was now more important than ever.

On 22 March, the day after the final cable from ‘NG’ was received, C and SIS colleague Col. Claude Dansey visited a diamond dealer in the City of London by the name of Schuyler and purchased diamonds to the value of £750

38

for Reilly to take to Moscow.

That same day MI5 were beginning what they thought would be a routine enquiry to confirm the biographical details Reilly had given on his application. Their memorandum, under Reilly’s name, addressed to the headquarters of Irish Command at Parkgate, Dublin, states:

We should be glad to know if a man of the above name is registered as having been born at Clonmel on 24 March 1874, and any partic-ulars you can let us have concerning his parents. Will you kindly let us have an answer as soon as possible, as the matter is urgent.

39

By 30 March, with no sign of a reply, MI5 sent a reminder memo. This clearly did the trick, for the following day Irish Command responded:

Reference your 267275/D of 22 and 30 March, the Police Department report that there is no record in the register of this man’s birth in Clonmel. Further enquiries are being made. (for) Major I.H. Price

40

It was a further three days before MI5 alerted Maj. Kendall of SIS to the fact that C’s new agent was not all that he claimed. By this point, the die had already been cast, for Reilly, or ST1

41

as he was now code-named, was aboard the Danish Merchant ship

Queen Mary,

steaming towards the Russian port of Archangel.

INE

T

HE

R

EILLY

P

LOT

F

our days after his departure, C sent a cable to the British mission in Vologda, alerting them of Reilly’s arrival:

On 25 March, Sydney George Reilli, lieutenant in the RFC, leaves for Archangel from England. Jewish-Jap type, brown eyes very protruding, deeply lined sallow face, may be bearded, height five foot nine inches. He will report during April. Carries code message of identification. On arrival will go to Consul and ask for British passport officer. Ask him what his business is and he will answer ‘Diamond Buying’. He has sixteen diamonds value £640 7s 2d as most useful currency. Should you be short of funds he has orders to divide with you. He will be at your disposal, utilise him to join up your organisation if necessary as he should travel freely. Return him to Stockholm end of June. More to follow.

1

Instead of following orders and disembarking at Archangel, Reilly left the ship at Murmansk. The port itself was in the hands of a company of British marines, who had been sent in on 6 March to guard Allied war materials thought to be at risk since the Bolshevik’s treaty with Germany. On leaving the merchant ship

Queen Mary,

Reilly was stopped for a routine inspection of documents and promptly arrested. He was confined aboard HMS

Glory,

where Maj. Stephen

Alley of SIS, who was on his way back to London, was summoned by Admiral Kemp to examine him. ‘His passport was very doubtful, and his name was spelt REILLI. This, together with the fact that he was obviously not an Irishman, caused his arrest’, said Alley.

2

Within days of his interview with C, Reilly had made contact with Litvinov, the Russian Plenipotentiary, who had a small office at 82 Victoria Street, Westminster. Making an appointment to see Litvinov proved easier said than done. After two unsuccessful attempts, Reilly’s third telegram finally managed to secure an interview on 23 March:

Regret not having heard from you in reply to my second wire. Will you kindly wire me when and where I can see you tomorrow Saturday morning. I shall wait for your telephone message to Regent 1332 from eight till ten thirty o’clock tomorrow morning.

3

As a result of the meeting, Reilly, or rather ‘Sidney George Reilli’, was issued with travel documents that permitted him to enter Soviet territory. Whether Litvinov had misspelled the name or whether this was the name by which Reilly identified himself to Litvinov is open to question.

4

A list of persons who had been issued with visas by Litvinov would certainly have been sent back to Russia on a regular basis, and Reilly may not have wished to encourage any comparison between himself and the Reilly of St Petersburg who had had such close connections with the Tsarist regime.

As soon as Alley appeared, Reilly produced a microscopic coded message from under the cork of a bottle of aspirins. Alley immediately recognised this as an SIS code and Reilly was quickly released.

5

Interestingly, Cumming’s telegram also reveals that it was originally intended that Reilly would return in late June, as indeed Beatrice Tremaine had told US investigators he would.

6

The reason Reilly was sent to Archangel seems quite clear, in that from there he could catch an express train directly to Moscow via Vologda. It seems equally apparent that he never had any intention of going straight to Moscow as ordered. One possible

reason for leaving the ship at Murmansk might have been the fact that he could get a direct rail connection to Petrograd from there, which he could not have done had he gone on to Archangel.

As it turned out, he spent the best part of four weeks in Petrograd before finally journeying to Moscow. If the purpose of his return to Russia had some connection with the family referred to by Norbert Rodkinson, or to possessions of his located somewhere in the city, this could well explain the delay.

7

Whatever it was that was occupying him in Petrograd, he found the time to send C a detailed report on 16 April, outlining his own home-grown solutions to the situation he found himself in the midst of:

Every source of information leads to definite conclusions that today BOLSHEVIKS only real power in RUSSIA. At the same time opposition in country constantly growing and if suitably supported will finally lead to overthrow of BOLSHEVIKS. Our action must therefore be in two parallel directions. Firstly with the BOLSHEVIKS for accomplishment of immediate practical objects; secondly with the opposition for gradual re-establishment of order and national defence.

Immediate definite aims are safeguarding MURMAN; securing ARCHANGEL; evacuation of enormous quantities of metals, ammunition and artillery from PETROGRAD which liable to fall to Germans within month; preventing Baltic Fleet from passing to Germans by their destruction or rendering it unserviceable; and possibly substitution of moratorium for final repudiation of foreign loans. All above objects can be accomplished only by immediate agreement with BOLSHEVIKS. For minor ones, such as MURMAN-ARCHANGEL a sort of semi-acknowledgement of their Government, better treatment of their ambassadors in Allied countries may be sufficient.

8

Building up to the point of his communication, Reilly states that the most potent factor in the equation is money. Only hard cash could effectively deliver all the other objects. Attributing German successes to their preparedness to use money, he coolly proposes to C that:

...this may mean an expenditure of possibly one million pounds and part of this may have to be expended without any real guarantee of ultimate success. Work must be commenced in this direction immediately and it is possibly already too late. If outlined policy should be agreed to, you must be prepared to meet obligations at any moment and at shortest notice. As regards opposition, imminent question is whether support to them comes from the Germans or from us.

9

Almost without batting an eyelid and with ten out of ten for sheer audacity, Reilly was effectively asking for at least one million pounds in cash, to be sent to him personally, post haste, without any guarantee that such action would actually achieve its objective. Needless to say, the canny C was having none it. Although Reilly was to be entrusted with funds later on, they were for specifically targeted objectives and certainly not in the region of the sums that Reilly was asking for here. What would have happened to the £1 million had C been gullible enough to agree is best left to the imagination.

In almost prophetic terms, Reilly concludes his report by saying that, ‘in any case, we have arrived at critical moment when we must either act or immediately and effectively abandon entire position for good and all’. As it would turn out, he took his own advice too literally.

On 7 May he arrived in Moscow in full dress uniform and headed immediately for the Kremlin. On reaching the main gates he informed the sentries that he was an emissary from the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, and demanded to see Lenin personally. Remarkably he was actually admitted, although he got no further than Lenin’s aide Vladimir Bonch Bruevich. Reilly explained that he had been sent to the Kremlin as the Prime Minister wanted first-hand news concerning the aims and objec-tives of the Bolshevik government. He also claimed that the British government was dissatisfied with the reports that he had been receiving from Robert Bruce Lockhart, the head of the British Mission in Moscow, and had instructed him with making good this defect. It would seem that Reilly’s interview was a very brief one. At 6 p.m. Robert Bruce

Lockhart received a telephone call ask-ing him to come over to the Kremlin.

10

On arrival he was asked if a man called ‘Relli’ was really a British officer or an impostor. Lockhart was incredulous when told the story of Relli’s visit that afternoon. He had never heard the name Relli, and diplomatically said that he would need to look into the matter and get back in due course.

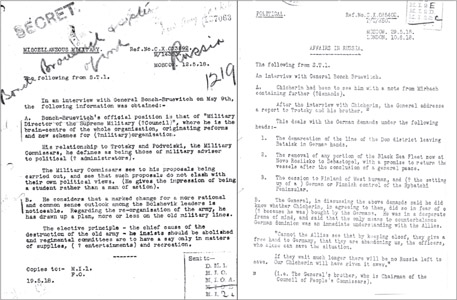

Two of Reilly’s ‘top secret’ reports from Moscow, commenting on Russia’s intentions towards Germany.

On leaving the Kremlin Lockhart immediately sent for Ernest Boyce, the head of SIS in Moscow, and angrily demanded an explanation.

11

Boyce confirmed that Reilly was a new agent sent out from London, but had no knowledge of his dramatic debut at the Kremlin. Boyce said he would send Reilly to Lockhart the following day to offer a personal explanation. Unsurprisingly, Reilly denied everything apart from the fact that he had been at the Kremlin on the afternoon of the seventh. Lockhart did not believe a word of Reilly’s account but said many years later that

his excuses were so ingenious that he had ended up laughing. It is unlikely that Reilly took any great heed of Lockhart’s threat to have him sent home and merrily carried on going his own way. It is also clear from this event that Lockhart had not had sight of Cumming’s telegram and was essentially in the dark about what was going on in London. Although Reilly’s story was a bold bluff, he was actually correct about London’s view of Lockhart, who the Foreign Office considered was providing inconsistent and ill-judged advice.

12

While the story of Reilly marching up to the Kremlin gates is vividly recited by several Reilly biographers,

13

the impression given is that this was his first and last attempt to deal directly with the Bolshevik authorities before going underground. A series of telegrams to London marked ‘Secret’ tell a very different story, however. They reveal that the day after his dressing down by Lockhart, he was, in fact, back at the Kremlin for what turned out to be one of several in-depth meetings with Vladimir Bonch Bruevich’s brother, Gen. Mikhail Bonch Bruevich. In a report headed ‘Miscellaneous Military’, Reilly referred in particular to two aspects of the meeting which had taken place on 9 May:

A. Bonch Bruevich’s official position is that of ‘Military Director of the Supreme Military (?Council)’, where he is the brain centre of the whole organisation, originating reforms and new schemes for (?military) organisation.

His relationship toTrotsky and Podvoiski, the Military Commissars, he defines as being those of military adviser to political (?administrator).

The Military Commissars see to his proposals being carried out, and see that such proposals do not clash with their own political views. (He gives the impression of being a student rather than a man of action.)

B. He considers that a marked change for a more rational and common sense outlook among Bolshevik leaders is noticeable. Regarding the reorganisation of the army, he has drawn up a plan, more or less on the old military lines.

The elective principle – the chief cause of the destruction of the old army – he insists should be abolished and regimental committees are to

have a say only in matters of supplies, (?entertainments) and recreation.

14

Despite the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, the report clearly confirms that all was not well between the Bolsheviks and the Germans. This is further amplified by Reilly’s report of 29 May in which he relates details of a meeting between Bonch Bruevich and Georgi Chicherin, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, at which new demands made by the German Ambassador Count Mirbach were discussed. The Germans wanted, in particular, three things: