Ace of Spies (21 page)

Trusting that the above may be sufficient for the purpose you have in view.

I have the honour to be,

Sir

Your obedient servant

S.G. Reilly, 2/Lt RFC23

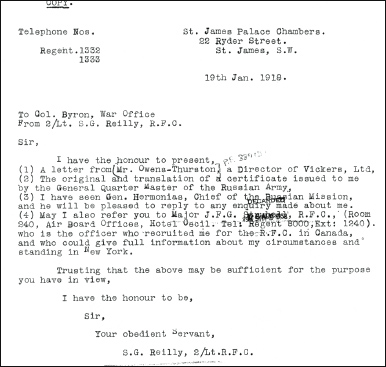

Attached, on Vickers headed notepaper, was the following testimonial:

To Whom it May Concern:

I have pleasure in stating that I have known Mr Sidney G. Reilly for thirteen years, and during that time I have had many opportunities of ascertaining his great abilities as a linguist. He was to my knowledge in Petrograd engaged in a great deal of Russian government business, and his knowledge of Russia always appeared to me to be extensive and accurate, and Russians of high official standing have testified to me as to the good work he did and his extensive knowledge of Russian affairs. I can only testify to his ability as a diplomatic businessman, whether the matter in hand is great or small, and during the thirteen years I have known Mr Reilly I have never heard anything disparaging to his character.

T.H. Owens-Thurston

24

If Owens-Thurston had really never heard anything disparaging about Reilly he must have been one of the few who had not. On the other hand, the letter does dispel the view ventured by Richard Deacon that Reilly was the great adversary of Vickers.

Whilst very much batting for Blohm & Voss, Reilly was careful to cultivate contacts and acquaintances wherever he could, particularly in rival firms such as Vickers.

The Russian military certificate Reilly enclosed was dated 8 August 1914 and issued by Maj.-Gen. Erdeli:

By order of the Chief of Staff of the Army, I request that the bearers of the present: the British subject Sidney George Reilly and the Russian subject I.T. Giratovsky be given assistance for the purpose of expeditious and unhindered passage over the frontier.

The above mentioned persons are commissioned by the Chief of the Artillery Department to acquire material and articles of armament for the needs of our Army.

25

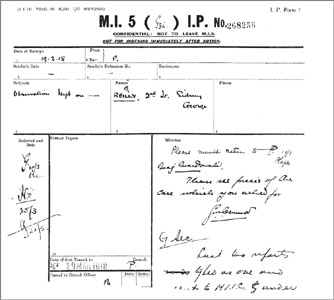

On 30 January SIS sent a standard enquiry form to MI5, with Reilly’s the only name listed:

Have you any objection to the following being employed by the Intelligence Department?

Sidney G. Reilly, RFC Club, Bruton Street and 22 Ryder Street, St James.

26

On 2 February MI5 likewise responded to SIS on their standard form of clearance:

We have nothing recorded against the above. Nothing is known to the prejudice of any of the above by the police.

27

There was one MI5 officer, however, who knew more than most about Reilly and would have been able to give chapter and verse about his mysterious background and clandestine activities – if only he had been able. Whether William Melville’s insight would have prejudiced Reilly’s application in any way was, by 2 February, of little or no consequence. Discharged from duty the previous September with kidney disease, Melville died in Bolingbroke

Hospital, Battersea, on 1 February 1918,

28

the day before the MI5 memo giving Reilly the all-clear was sent to SIS.

By March 1918, MI5’s investigation into Reilly’s background was making little headway.

As a result, an appointment was made for Reilly to attend an interview with C on 15 March at SIS headquarters. While MI5 found nothing detrimental on Reilly, C clearly felt that he needed to know more about the mysterious Mr Reilly. On 28 February he sent a telegram to the SIS station in New York,

29

informing them of the task he had in mind for Reilly and asking for full particulars on his reputation and background. None of these enquiries would, of course, have been necessary if Reilly had been a known quantity.

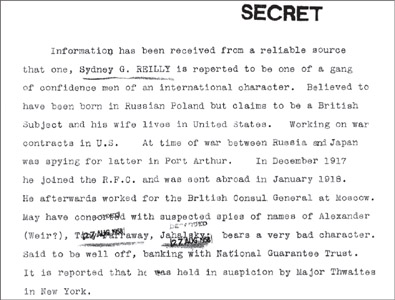

At 10.00 a.m. on 4 March a cable was received at SIS Headquarters from Norman G. Thwaites (NG) in New York, replying to C’s enquiry:

With reference to your telegram No. 206 of the 28th; SYDNEY REILLY is a British subject married to a RUSSIAN JEWESS who has made money since the beginning of the war through influence

with corrupted members of the Russian purchasing commissions. He is believed to have been in PORT ARTHUR in 1903 as a spy for Japan. We kept him under observation in 1916. We consider him untrustworthy and unsuitable to work suggested.

NG

30

Not to be deterred by this damning reply, C sent another telegram to New York the following day seeking further clarification. In the meantime, MI5 were also asked to keep a tab on Reilly pending the progress of his application. On 9 March they reported that despite placing him under surveillance for three days, ‘nothing was discovered about his movements, owing to the fact that he usually moved about in taxis and it was nearly always impossible to get another cab’.

31

Conjuring up visions of a Keystone Cops chase, the ‘tailers’ were reduced to catching buses to the destinations Reilly was thought to be heading for – usually the Savoy Hotel. On one occasion they did actually manage to hail down a cab, only to be told by the driver that Reilly’s cab had a more powerful engine and was not worth his while following!

MI5 received a wealth of reports on Reilly’s unsavoury past.

When Reilly made an application to the War Office for intelligence work in January 1918, he was careful to submit glowing testimonials and references.

The watch on his Ryder Street lodgings and interviews with others at the address led MI5 to report that he was ‘very respectable, pays bills quite regularly, lunches and dines at the Savoy and Berkeley Hotels and is always in by midnight’.

32

At 2.20 p.m. on 14 March, New York’s reply to C’s second cable was received at Whitehall Court:

Your telegram No. 210 of 5th:

Official of National Powder Bank has given us the following confidential statement on man in question whom he has known for several years: A shrewd businessman of undoubted ability but without patriotism or principles and therefore not to be recommended for

any position which requires loyalty as he would not hesitate to use it to further his own commercial interests. He has been connected with Government contracts in RUSSIAN–JAPANESE and present wars and has undeniably excellent knowledge of those countries.

Above opinion precisely confirmed by our own estimate of man.

NG

33

The following day, with no knowledge of the cables that had been criss-crossing the Atlantic on his behalf, Reilly presented himself at 2 Whitehall Court to keep his appointment with ‘C’.

34

Meeting ‘the Chief’ was a formality that all potential agents had to undertake, and Reilly was no exception. Paul Dukes, a future friend and SIS colleague of Reilly, gave a rare and unique account of this no doubt awesome experience in his book,

Red Dusk and the Morrow.

On arrival at Whitehall Court, Dukes was met by a nameless colonel and escorted to C’s office:

MI5’s surveillance of Reilly proved no easy task.

We entered the building and the lift whisked us up to the top floor. Leaving the lift my guide led me up one flight of steps so narrow a corpulent man would have stuck tight, round unexpected corners, and again up a flight of steps.

‘The sanctum of the Chief’ was ‘a low dark chamber at the extreme top of the building’. The colonel knocked, entered, and stood at attention. A nervous Dukes followed. He recalled:

The writing desk was so placed with the window behind it that on entering everything appeared only in silhouette. It was some seconds before I could distinguish things. A row of half a dozen extending telephones stood at the left of a big desk littered with papers. On a side table were numerous maps and drawings, with models of aeroplanes, submarines and mechanised devices, while a row of bottles of various colours and a distilling outfit with a rack of test tubes bore witness to chemical experiments and operations. These evidences of scientific investigation only served to intensify an already overpowering atmosphere of strangeness and mystery. But it was not these things that engaged my attention as I stood nervously waiting. My eyes fixed themselves on the figure at the writing table. This extraordinary man was short of stature, thick set, with grey hair covering a well-rounded head. His mouth was stern, an eagle eye, full of vivacity, glanced – or glared, as the case might be – piercingly through a gold-rimmed monocle. The coat that hung over the back of the chair was that of a naval officer.

35

Quite what impression C, Mansfield Cumming, made on Reilly is unknown. Cumming himself briefly recorded his impressions of Reilly in his diary for 15 March:

Scale introduced Mr Reilly who is willing to go to Russia for us. Very clever – very doubtful – has been everywhere and done everything. Will take out £500 in notes and £750 in diamonds which are at a premium. I must agree tho’ it is a great gamble as he will visit all our men in Vologda, Kief, Moscow etc.

36

The impression that Reilly was ‘very doubtful’ could only have been reinforced by the arrival of the final cable from New York at 2.25 p.m. on 21 March:

Further my telegram No. 201 of 13th:

MACROBERTS reports he likes Reilly personally but knows little of him. Another official of the bank gives me the following information from a man who has known REILLY for years: R is GREEK Jew: very clever: entirely unscrupulous. Present war has made about two million dollars on Russian contracts. Has connections in almost every country including Germany, Japan and Russia. ENDS. In connection with the above may I point out that there must be a strong motive for REILLY leaving profitable business here and wife of whom he is said to be very jealous, to work for you.

NG

37

C had a reputation as a risk taker who was willing to go against the grain. There could be no greater demonstration of this than his decision to give Reilly a chance in spite of the volumes of negative feedback he had so far received. The risk, in C’s mind, must have been far outweighed by the vital operational need for reliable Russian intelligence. Negotiations between the Bolsheviks and the Germans had been taking place at Brest Litovsk, on and off, since 22 December 1917, and it was becoming increasingly apparent that matters were now coming to a head. While C was still exchanging cables with New York, the two sides finally signed the Treaty of Brest Litovsk on 3 March. It was a bitter pill for the Russians to swallow, involving a great loss of land and swingeing reparation payments. Lenin, however, was determined to pull out of the war, as he knew his infant regime’s survival depended upon it. For the Germans it meant they could now throw their full weight against the Allies on the Western Front.