Ace of Spies (20 page)

He first appears in US Immigration records on arrival in New York on 10 June 1903 aboard the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, which sailed from Bremen, Germany. Over the next two decades he, his first wife Susanne and second wife Corinne, crop up repeatedly, criss-crossing the Atlantic. Prior to the First World War, all journeys to New York began in Germany. Although he always described himself as a US citizen, as we have seen, he was never able to prove that he was born in the USA. While his general statements about Reilly’s character are very much along the lines of a good many other people who knew him, his claim about Reilly being born in Bendzine and allegedly deserting his family in 1916 are very different matters. Whether Rodkinson’s statements were true or not, he was certainly not an unblemished witness.

The result of the investigation was, to put it kindly, inconclusive. Roger Welles, the director of Naval Intelligence, who had initiated the enquiry back in April 1917, probably best summed it up, when, two months after the end of the war, he wrote to the director of the Bureau of Investigation, Bruce Bielaski, enclosing a copy of the file containing the results of the investigation:

While the investigation disclosed nothing definite, there is a mass of interesting data that might be of use to your department should any of the individuals in question come under your observation. This office believes that these men are international confidence men of the highest class.

54

On that rather resigned note, Welles signed off. In spite of everything he now knew about Reilly’s nefarious disposition, even he would have found it hard to comprehend that within months of joining the RFC, the ‘international confidence man’ would be walking into the London headquarters of SIS for a personal audience with C, the service’s legendary chief.

IGHT

C

ODE

N

AME

ST1

W

hen Col. Abbott of the British Mission in New York first heard that Reilly had been seen wearing the uniform of a British officer he was ‘astonished’.

1

Knowing of Reilly’s dubious form, he could not understand how such a blackguard had been permitted to join the British Army, let alone be awarded a commission. Another officer, Col. Gifford, had spoken with the equally incredulous Maj. Thwaites, who implied he would be making clear his views to London in no uncertain terms.

2

Gifford assumed from this that Reilly would be recalled and probably asked to resign. In fact, nothing of the sort happened. Thwaites’ attitude is somewhat strange to say the least in light of the following passage from his 1932 autobiography:

In 1917 as a man of about thirty-eight he [Reilly] came to me in New York with the request that I should get him into the service. He felt that he ought to be doing his bit in the war… Reilly expressed the desire to join the Royal Air Force. I sent him to Toronto to the officer in command and he was promptly given a commission. But he was too valuable a find to be wasted as an Equipment Officer, to which department he was assigned. I reported to HQ at home that here was a man who not only knew Russia and Germany, but could speak almost perfectly at least four languages. His German was indeed flawless, and his Russian hardly less fluent.

3

Thwaites goes on to relate how, as a result of his report to London, Reilly was summoned for an interview with C, ‘the mysterious chief of hush-hush work’, and then assigned work firstly in the Baltic and then East Prussia before being dispatched to Russia. It is no exaggeration to describe the comparison between this 1932 account and the reality of 1917 as breathtaking. Weinstein, who in 1932 is described as ‘one of the nicest Russians I know’,

4

was at the time referred to as an undesirable character and former brothel keeper who was fraternising with the enemy.

5

Reilly, who is also referred to in the most complimentary of terms in 1932 was, of course, given an even blacker report back in 1917.

Neither, it must be said, does Thwaites’ version of recruiting Reilly sit comfortably with the account given within the telegrams exchanged between SIS headquarters in London and the SIS New York station during February and March 1918. With Reilly dead and Thwaites’ original reports and telegrams safely out of the public domain, he probably saw little harm in taking credit for the recruitment of Reilly, who in 1932 was on the crest of a posthumous wave of celebrity as the great ‘Master Spy’, featured in strip cartoons and serials in England and on the continent.

Contrary to claims made by countless Reilly writers, there had been no relationship whatsoever between Reilly and SIS before 1918. This is made clear by C’s personal diary, which indicates that Reilly had been proposed as someone who could be helpful to the department by Maj. John Scale, latterly of the SIS station in Petrograd.

6

C’s diary further reveals Scale to have been liaising with the British Army in Canada and preparing agents with Russian backgrounds or experience for work in Russia.

7

Reilly had been brought to Scale’s attention shortly after his enlistment by Maj. Strubell, the officer who had dealt with his commission and to whom he had volunteered his services for work in Russia.

While it seems evident that Reilly offered his services as opposed to being approached, his motive for doing so is far from clear. To believe that he wished to leave his wife, his mistress and his comfortable life of prosperity in New York to ‘do his bit’

8

in

the war, as suggested by Thwaites, is naïve in the extreme. After all, Reilly had shown not the slightest interest in doing ‘his bit’ before. Time and again it has been demonstrated that he was not someone who was in any way motivated by patriotism or ideology, but was driven purely by greed and self-interest.

Richard Spence has suggested that Reilly’s departure from New York was a direct consequence of his supposed involvement in the sabotage campaign of Kurt Jahnke,

9

and that his subsequent RFC enlistment in Toronto was somewhat earlier than indicated by his Military Service Record.

10

From this, and Thwaites’ statement that Reilly ‘undertook work in Russia when Kerensky was dropping to his doom’,

11

Spence develops the theory that Reilly went to Russia before the Bolshevik Revolution not after it. He pinpoints Reilly’s arrival in Russia as being in early August 1917, when a special RFC training wing arrived there. Although unable to locate a personnel roster, he clearly believes that Reilly was a member of this unit:

Reilly’s disappearance [from New York] neatly coincides with the arrival in Russia during early August of a special RFC training wing. This unit was attached to the existing British military equipment mission under Gen. F.C. Poole. Reilly’s service record lists him as an equipment officer, and he and Poole were to cross paths in Russia in 1918 and 1919.

12

However, Air Mechanic Ibbertson recorded in his diary a full list of officers and other ranks who served with him in this unit and Reilly’s name is conspicuous by its absence.

13

Bearing in mind the fact that the Jahnke sabotage theory is at best built on a foundation of sand, it has to be said that the wider hypothesis put forward by Spence is not substantiated by hard evidence. On the contrary, recently discovered correspondence between Reilly and his mistress Beatrice Tremaine clearly indicates that during the period July–December 1917, Reilly was in fact resident in the city of Toronto, at the King Edward Hotel. Situated on King Street

East, the hotel was not only Toronto’s most luxurious, but was situated close to the Royal Flying Corps No. 4 School of Military Aeronautics at the University of Toronto, where Reilly trained prior to his departure for England in December 1917.

14

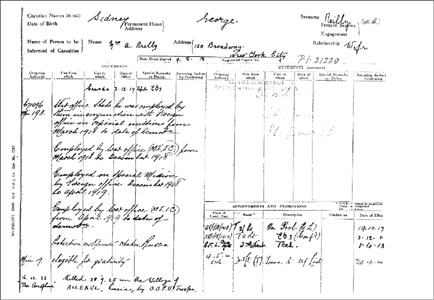

Reilly’s RAF service record (note next of kin ‘Mrs A. Reilly’).

If one is looking for persuasive coincidences, then surely the revolutionary events that were being played out in Russia during October and November 1917 are far worthier of consideration? Reilly initially enlisted with the RFC in Toronto on 19 October 1917, and was placed ‘on probation’ pending confirmation of a commission.

15

Several weeks before, the Bolsheviks had achieved majorities in both the Moscow and Petrograd Soviets, thus heightening speculation that an armed insurrection might be on the cards. When the Bolshevik takeover actually took place on 7 November that year,

16

Reilly was already undergoing training at the School of Military Aeronautics.

17

Bearing in mind what we already know of his motivations and priorities, what personal reasons might he have had for wanting

to return to Russia in such haste? Once the Bolsheviks had taken power it would not have been easy for a non-Russian civilian (as ‘Sidney Reilly’ officially was) to gain entry.

It is most likely that in 1914 Reilly’s plan was to go to New York to make as much money as he could from war contracts while the conflict lasted. Britain was not alone in thinking the war would be ‘over by Christmas’, and he no doubt wanted to make his mark before it ended. It is equally likely that most of his possessions and valuables remained behind in St Petersburg pending his return. The abdication of the Tsar in March 1917 would not have particularly unnerved him for the Provisional Government was resolved to continue the war against Germany as an ally of France and Britain, and many assumed that the Tsar’s overthrow would actually restore Russia’s fortunes on the battlefield. Furthermore, the Provisional Government’s assumption of power would not have had any adverse effects on his ability to re-enter the country or to retrieve money or property lodged there. The threat of a Bolshevik seizure of power was something entirely different. If successful, there was a strong possibility that they would seal off the country to foreigners, and there was no telling what might happen in such revolutionary upheaval to any valuables he had secreted away.

If he actually had a wife and children in Petrograd, as Rodkinson alleged, he may well have wanted to get out to them now that they were effectively trapped. In support of this theory it should be noted that when, in November 1911, Reilly had briefly been under surveillance from Russian counter-intelligence, letters addressed to him had been intercepted from his ‘wife’. She was referred to in the surveillance report as, ‘the daughter of a Russian general living abroad’.

18

This wife could not be Margaret, who, although living abroad, was not the daughter of a Russian general. Neither could she be Nadine, the daughter of a colonel, who in 1911 was living in St Petersburg with her husband Petr at 2 Admiralty Quay, several blocks away from Reilly’s apartment at 22 Novo Isaakievskaya. As another intriguing aside,

the

Alphabetical Directory of the Inhabitants of the City of St Petersburg,

contains the name of one Anna Reile, who appears in the editions for 1913, 1914 and 1916.

19

In addition, it has already been noted in Chapter Three that on enlistment Reilly had to declare the name of the person to be informed in the event of him becoming a casualty of war. That person is recorded as ‘Mrs A. Reilly of 120 Broadway, New York City’. The address was, of course, Reilly’s office, then managed by two reliable associates, Dale Upton Thomas and Alexandre Weinstein. Nadine was then living outside New York and was well provided for by bank accounts he had set up before departing. If Mrs A. Reilly was Anna, the reason she was to be specially taken care of may well have been the children. While his motives for volunteering remain somewhat open to question, the months between his enlistment in Toronto and his return to Russia are vividly, and at times amusingly, recounted in the annals of SIS and MI5.

Thirteen days after the confirmation of his commission as a second lieutenant in the RFC, Reilly’s name appears on a Canadian roster, dated 3 December 1917,

20

of officers who would shortly be posted overseas. In Reilly’s case this meant England, where he arrived on a chilly New Year’s Day and booked into suite 32 at the Savoy Hotel,

21

with lieutenants H.A. Kelly and M. Marks. After a week Kelly was posted to France and Marks to 39 Squadron in Shropshire. Reilly, though, ventured but a short distance to lodgings at 22 Ryder Street, St James.

On 13 January he met Maj. Scale, who had arrived in London from Petrograd on 9 January.

22

Scale briefed him on the formalities that must be dispensed with before his application could be taken further. These formalities clearly included the submission of testimonials and supporting documentation, for on 19 January he wrote to Col. Byron at the War Office, as directed by Scale:

Sir,

I have the honour to present:

1. A letter from Mr Owens-Thurston, a director of Vickers Ltd.

2. The original and translation of a certificate issued to me by the General Quarter Master of the Russian Army.

3. I have seen Gen. Germonius, chief of the Russian Mission and he will be pleased to reply to any enquiry made about me.

4. May I also refer you to Maj. J.F.G. Strubell RFC (Room 240, Air Board Offices, Hotel Cecil. Tel. Regent 8000, ext. 1240), who is the officer who recruited me for the RFC in Canada, and who could give full information about my circumstances and standing in New York.