Ace of Spies (15 page)

The general opinion among them is that the gr.Kr

56

project will be built after the Admiralty plans. I was strongly advised that you and Bisch should contact Georg often to keep him continuously informed about Putt and their suggestions. Georg is very interested in this and it is very important that his interest is maintained and that in the future

he is informed about us directly by you or Bisch and not from P or B. I am furthermore told (but I must have your word that this remains between you and I) that Jach is very unwelcome at Georg’s and that in our own interests we should not send him there. You know how dear this common friend is to me but I consider it my duty to tell you this. It is doubtful whether it is planned to build the gr.Kr in Germany, and indeed there are national and political reasons for this. In regard to the kl.Kr,

57

it is probable that no one except B and V would be considered.

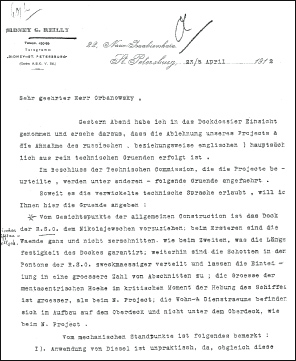

On 25 April 1912 Reilly hypocritically complained to Obanowsky of insider dealing.

It can be assumed that the programme will be settled in the Duma at the start of May; there is no doubt that money will be received. Serious work should get going immediately after Easter and the contracts will be allocated by the end of July. During the holidays I will have various opportunities to see my friends and will work with them on the aspects that interest you. For now and wishing you the most pleasant of holidays,

Your very loyal

Sidney G. Reilly

58

In reality, the letter is a subtle example of Reilly’s ‘divide and rule’ approach to life. He not only casts aspersions on the judgement of Count Lubiensky and his ability to get a more favourable verdict on the proposal, he also tries, in a very underhanded way, to drive a wedge between Orbanowsky and his ‘dear friend’, Lubiensky’s senior colleague Jachimowitz. Ironically, Reilly is the first to complain in this letter about the ‘insider-information’ swindles being perpetrated on Blohm & Voss, but his own hands were far from clean when it came to obtaining the particulars of rival tenders. In September of that year, Sir Charles Ottley, of the British shipbuilders Armstrongs, visited St Petersburg with a view to tendering for contracts.

59

Although Armstrongs had initially shown some reluctance to participate, they seem to have been persuaded to do so by Alexei Rastedt, who was ultimately appointed their Russian representative. Alexei Rastedt was no newcomer to the shipping business, and had, several years previously, been one of Reilly’s ‘background men’. When eventually Armstrongs did decide to enter a last-minute tender, this caused much friction between themselves and their Tyne- side neighbours, Vickers, which was gleefully picked up by the St Petersburg press. When the contracts were eventually awarded, there was a very strong suspicion that Armstrong’s bid had been reported to one of their rivals.

Vickers’ ruthless and unscrupulous representative Basil Zaharoff was the biggest player in the arms trade at this time, and it is hardly surprising that his name has been subsequently linked with the equally unsavoury Reilly. Zaharoff was featured as a prominent character in Troy Kennedy-Martin’s television adaptation of

Ace of Spies,

60

despite the wholesale lack of evidence linking the two. Richard Deacon, who also proffered the theory that Reilly was an Ochrana agent, believed that ‘one of the tasks which the Russian Secret Service set for Sidney Reilly was to build up a dossier on the notorious international arms salesman, Basil Zaharoff’.

61

Ochrana records at the Hoover Institute in California and in the State Archive of the Russian Federation in

Moscow contain no corroboration for this belief, nor for any kind of association between Reilly and Zaharoff.

Not unsurprisingly, Reilly was viewed with suspicion by many of those he came into contact with in St Petersburg. Some thought he was an English spy, others said he was spying for the Germans. In November 1911 the Suvorins had been concerned enough to make enquiries about Reilly and his activities. Boris Suvorin initially asked his associate Ivan Manasevich-Manuilov, a

Novoe Vremia

journalist, to check with Stephan Beletsky, the head of the St Petersburg Police Department. Beletsky referred the enquiry to Gen. Nicolai Mankewitz, head of counter-intelligence. As a result Reilly was briefly kept under close surveillance and had his mail intercepted. As with the previous year’s check initiated by the Interior Ministry, nothing that would give any cause for concern was found and Mankewitz called off the surveillance and closed the file.

62

Among the regular correspondents Reilly kept in touch with was his cousin Felitsia, now living in Warsaw. Their close relationship is evident from a verse from the 29th stanza of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam he sent her:

Into this universe, and why not knowing,

Nor whence, like water, willy-nilly flowing,

And out of it, as wind along the waste,

I know not whither, willy-nilly blowing

Ironically, Manasevich-Manuilov was himself an Ochrana agent and had supplied information on Boris Suvorin and his fellow directors to the Ochrana authorities.

63

As the storm clouds of the First World War approached, concern about German spies intensified and Manasevich-Manuilov turned his attention to supplying lists of suspects. With growing tensions between the two countries, naval contracts dwindled and eventually petered out altogether. Thankfully for Reilly, the clouds of war on the horizon were to have a substantial silver lining.

IX

T

HE

H

ONEY

P

OT

W

hile Reilly and Nadezhda Massino were holidaying at St Raphael on the French Riviera,

1

a Bosnian Serb student named Gabriel Princip assassinated the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Archduke Francis Ferdinand, in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. This set off a chain reaction that within six weeks would envelop the great powers in a world war. On 5 July Germany declared its support for Austria, who in turn issued an ultimatum to Serbia that was purposely designed to make acceptance impossible. As the great powers squared up to each other, Reilly hastily departed for St Petersburg, leaving Nadezhda to continue the holiday alone.

On his arrival back in the Russian capital, he soon learned from his contacts that Russia had resolved to take military action against Austria if Serbia was attacked. On 28 July Austria declared war on the Serbs and Tsar Nicholas mobilised Russian forces the following day. Germany’s declaration of war on Russia on 1 August found the Russians ill prepared. What would turn out to be a catastrophe for Russia, and the Tsar in particular, would provide Reilly’s big chance, not only to make the millions he dreamed of, but also to make his mark on history.

As the hostilities commenced, a small army of contractors and brokers set off to secure the guns, ammunition, powder and

general military equipment that the Russian war effort would need in abundance. Within days of war being declared, Reilly had been commissioned by Abram L. Zhivotovsky of the Russo-Asiatic Bank and the Russian Army to acquire munitions for the Russian Army.

2

Before departing for Tokyo in early August he wrote to both Margaret and Nadezhda.

3

For Margaret it would be the last letter she would receive from him until the war was over. Once in Tokyo, Reilly successfully secured a large powder deal with Taka Kawada and Todoa Kamiya of Aboshi Powder Company,

4

and the contract was then put in the hands of Reilly’s agent in Japan, William Gill.

While Reilly was in Tokyo, Samuel M. Vauclain, vice president of the Baldwin Locomotive Works of Philadelphia, arrived in St Petersburg seeking contracts for narrow gauge locomotives and munitions.

5

Although Reilly was absent from St Petersburg, Vauclain found that his main competitor for the munitions contract was Reilly. It was obvious to him that Reilly had tremendous political backing in Russia which emanated from the office of the Tsar’s cousin, the Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, a contact Reilly had made at the time of the Russo-Japanese War through Moisei Ginsburg. The grand duke showed Vauclain a telegram from Reilly, sent through his London office, in which he had cut his contract price.

6

However, on this occasion, Vauclain won the contract, and took back an order for 100,000 military rifles, converted to use Russian cartridges, to be manufactured by the Remington Arms Company. Not long after, Vauclain shrewdly converted the Baldwin plant at Eddystone, Pennsylvania, which was running two thirds below capacity, to manufacture arms and munitions.

Before the war was over, the United States would manufacture over a third of all Russia’s war munitions and equipment. American industry quickly saw the opportunity that beckoned, as indeed did brokers such as Reilly. Having concluded the powder deal in Tokyo, Reilly booked a passage on the SS

Persia,

which sailed from Yokohama Docks bound for San Francisco on 29 December

1914. It arrived in San Francisco on 13 January 1915.

7

On arrival he declared to US Immigration that he was a forty-one-year-old merchant of British nationality, born in Clonmel, Ireland. He further declared that this was his first visit to the United States, that his journey had started in St Petersburg and that he had a through ticket to his final destination, New York City.

8

Apart from his claim to have been born in Clonmel, the rest of the informa-tion he gave was true. From San Francisco he travelled to New York by train, where he took an apartment at 260 West 76 Street.

9

Through the Russo-Asiatic Bank he was introduced to Hoyt A. Moore, an attorney specialising in import and export matters. Moore not only provided advice to the new arrival but also recommended an acquaintance, thirty-year-old Dale Upton Thomas, whom Reilly took on as his office manager. Hays, Hershfield and Wolf, at 115 Broadway, another Moore introduction, became Reilly’s legal representatives. A short walk away, with its classical arched entrance and grand marbled lobby, was the Equitable Building, at 120 Broadway, which Reilly chose as his New York base. He took 2722, a prestigious high-floor suite overlooking the downtown financial district of Manhattan, from where he and Thomas were to operate for the next three years.

10

The Equitable Insurance Company was well established in Russia

11

and its Broadway building was already home to a number of Russian tenants, a good number of whom were dealing in wartime munitions contracts in America. It was also through Hoyt Moore that Reilly met Samuel McRoberts, vice president of the National City Bank, who was also keen to profit from the honey pot that the war in Europe promised to deliver. To this end he procured Reilly’s appointment as managing officer of the Allied Machinery Company, which was also based at 120 Broadway.

12

It has been suggested that Allied Machinery was a Reilly front company, when in fact it had been established since 1911. McRoberts was elected to the board of directors the following year, from which position he was able to introduce Reilly into the company. Company records indicate that Reilly was neither

a shareholder nor a director, and was purely an employee, albeit a senior one.

13

The purpose of the company was to ‘manufacture, produce, buy, sell, export, lease, exchange, hire, let, invest in, mortgage, pledge, trade and deal in, and otherwise acquire and dispose of machinery, machine-tools and accessories, machinery products and parts and goods, wares and merchandise of every kind and description’. In other words, it had an extremely wide remit and was ideal for trading within the new munitions marketplace.

While it is clear that Reilly used his exceptional networking skills to their full advantage and no doubt made the acquaintance of a large number of businessmen in NewYork, these often tenuous relationships have been used to associate Reilly with a range of events with which he had no connection whatsoever. His rivalry with J. Pierpont Morgan, the Anglophile American financial magnate, is a prime example. Morgan, best remembered today for his ownership of the White Star Line and its ill-fated flagship the RMS

Titanic,

was the main player in the allied quest for munitions in the United States. His desire to monopolise the arms trade on behalf of the Allied powers alienated him from the small army of independent brokers, like Reilly, who sensed they would be squeezed out of the munitions marketplace if Morgan succeeded in his aims. The very month that Reilly arrived in New York, Morgan had signed an agreement with the British Commercial Agency that made him the sole agent in the USA for munitions purchases. As part of this deal, Morgan made his ambitions clear so far as the Russian market was concerned, by offering Russia a $12 million credit on the proviso that his company acted as agent for all contracts signed as a result.

14

On 3 February 1915 an explosion rocked the DuPont Powder Plant in DuPont, near Tacoma, Washington. According to the

Tacoma Daily News

(an afternoon publication):

With a detonation that was heard for miles, the black powder plant of the DuPont company at DuPont, near Tacoma, exploded at 9.30

this morning, demolishing the building, killing Henry P. Wilson, thirty- five, unmarried, and seriously injuring Harry West, married. As Wilson and West were the only men in the vicinity at the time officers of the company said the exact cause could not be given. The roof was lifted off the building and the sides blown to pieces, corrugated iron being scattered for a radius of 200ft. The building was one of a chain and was known as the ‘press’ building, where the powder is pressed into cakes. Wilson’s body was blown about 50ft from the building. West was thrown about 150ft.

15