A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (15 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

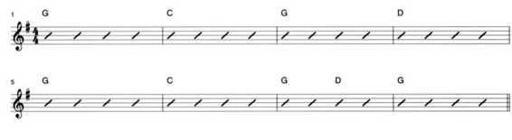

Figure 4-11. This eight-bar progression, used in many country and bluegrass tunes, consists of two four-bar phrases. The first phrase ends on the dominant (D in the key of G), making it a half cadence. The second phrase ends with a V-1 progression. Because the last chord in the phrase is a 1, the phrase ends with a full cadence.

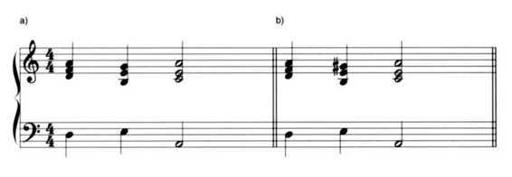

Figure 4-12. In a deceptive cadence, a I chord is expected, as in (a), but instead a different chord is substituted for the I, most often a minor VI. A deceptive cadence using the minor VI is shown in (b). The deceptive cadence in (c) uses a technique we'll look at more closely in Chapter Five: The E major triad is not part of the key of C major, but instead is a secondary dominant leading to the A minor triad. In other words, although this progression is in C major, it contains a V-I progression in the key of A minor.

MAJOR & MINOR KEYS

Up to now, we've been talking about major scales and mostly using progressions in major keys as examples. Many pieces of music are written, however, in which a minor chord is used as the tonic. Such pieces are said to be in a minor key.

Each of the 12 key signatures can be used either for a major key or for the minor key that uses (mostly) the same set of accidentals. The minor key in this case is the one whose scale starts on the VI of the major scale. For instance, A minor corresponds to C major (because A is the VI in the key of C major), D minor corresponds to F major, and so on. The key of A minor is said to be the relative minor of the key of C major. In the same way, E minor is the relative minor of G major, F# minor the relative minor of A major, and so on.

We can use the same terminology when referring to notes and chords in a minor key that we would use in a major. Figure 4-13 shows how the basic terms would be applied to the key of A minor. As you play this example, you should notice one or two important things. First, because the diatonic triads in A minor are exactly the same as those in C major, it's a little difficult to tell, simply by listening, which key you're in. Your ear may tend to drift back toward hearing the music in C major, because the major scale exerts a kind of magnetic pull. Second, the dominant and subdominant triads in the minor key are minor triads. Because of this, the dominant-tonic progression in particular isn't very forceful.

Figure 4-13. Diatonic triads in the key of A minor. As noted in the text the term "leading tone" is usually used to refer to the note below the tonic, not to an entire triad built on that note.

The solution to both of these difficulties, which has been commonly used by composers since before the time of Bach, is to alter the 3rd of the dominant when the music is in a minor key. In the key of A minor, more often than not a composer will use an E major chord as the dominant. Once in a while, the subdominant may also have a raised 3rd, but most often this harmony is the result of voice-leading considerations. An altered dominant in A minor is shown in Figure 4-14.

Figure 4-14. Two IV-V-1 progressions in A minor. In (a), the V chord is strictly diatonic; it uses the Gq in the key signature. In (b), the V chord has been altered to E major, providing a G# leading tone. This provides a much stronger cadence.

At this point, however, our harmonic system has developed a new ambiguity. Looking again at Figure 4-13, what happens to the III chord if we sharp the 3rd of the V chord? In place of a C major III in A minor, we suddenly have a Caug III. This may or may not be desirable at any given spot in the chord progression.

In practice, composers deal with this ambiguity by freely altering the 6th and 7th steps of the minor scale, or not doing so, based on what's needed at the moment. Both the 6th and 7th steps of the minor scale are heard in two different ver sions, altered or unaltered, sometimes within the same measure. Most often, the 7th step is raised to form a leading tone for harmonic reasons - that is, to provide a major dominant triad - while the 6th step is raised for melodic reasons in a line that is moving upward from the 5th to the 7th. The inherent instability of the 6th and 7th steps of the minor scale gives music in minor keys a kind of chromatic richness not found in the major keys. This fact, in combination with the darker color of the minor I chord itself, is what causes music written in minor keys to be more emotion-laden or plaintive than similar music written in a major key.

When we turn our attention, in Chapter Seven, to scales, we'll take a closer look at the variations in the minor scale.

As noted above, the relative minor of a major key has its root on the 6th step of the major scale. To look at it another way, the tonic of the relative minor is a minor 3rd below the tonic of the major. Each major key also has a parallel minor key. The tonic of the parallel minor is the same as the tonic of the major. G minor, for instance, is the parallel minor of G major.

OTHER DIATONIC PROGRESSIONS

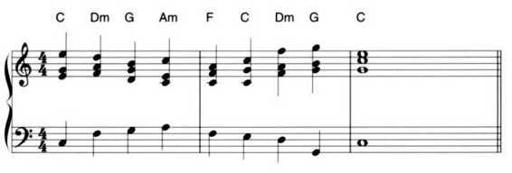

Even with the limited resources provided by diatonic triads, we can create a number of usable, interesting progressions. One possible example is shown in Figure 4-15. Also, many rock songs use progressions that involve only diatonic triads. Whole songs have been written using nothing but an endlessly repeated I-IV-I-IV progression. And you probably learned to play the music in Figure 4-16 (a I-VI-IVV progression) when you were eight or nine years old.

This figure illustrates an important property of chord progressions, especially as they're used in pop music. Some progressions have a natural tendency to repeat. The end of the progression tends to lead the ear back to the beginning. A repeating progression - or, for that matter, a repeating bass line, rhythm, or melody - is called a riff. The word can also be used as a verb: "Then you riff on the I-VI for 32 bars'

Figure 4-15. A simple but musical progression that uses only diatonic chords.

Figure 4-16. A familiar diatonic progression that repeats. Rather than stick with boring block chords, I've notated this example using a bouncy rhythm. From time to time, the examples in this book will be given with rhythms. Please feel free to try any of the block chord examples using any rhythm pattern that appeals to you.

QUIZ

1. Define the following terms: changes, harmonic rhythm, relative minor, deceptive cadence, riff.

2. What is the diatonic III chord in the key of A major? The V chord in F major? The II chord in B minor? In each case, identify the type of triad (major, minor, augmented, or diminished).

3. What chord follows the dominant in an authentic cadence?

4. Which diatonic triad or triads are most often altered in a minor key? Which note in each triad is altered, and how is it altered?

5. Identify all of the chords in Figure 4-15 as I, II, III, IV, etc. Also, indicate which of the chords are inverted. Which inversions are used?

6. Which of the diatonic triads in the major scale is used least often, and why is it not used?