A History of the World in 100 Objects (48 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

The two judges of the Chinese Underworld

Chinese Tang Tomb Figures

AROUND

AD

728

It’s a sure sign of middle age, they say, if, when you pick up the newspaper, you turn first to the obituaries. But middle-aged or not, most of us, I suspect, would love to know what people will actually say about us when we die. In Tang China around

AD

700, powerful figures didn’t just wonder what would be said about them: eager to fix their place in posterity, they simply wrote or commissioned their own obituaries, so that the ancestors and the gods would know precisely how important and how admirable they were.

In the Asia gallery at the north of the British Museum stand two statues of the judges of the Chinese Underworld, recording the good and the bad deeds of those who had died. These judges were exactly the people whom the Tang elite wanted to impress. In front of them stand a gloriously lively troupe of ceramic figures. They’re all between 60 and 110 centimetres (25 and 40 inches) high, and there are twelve of them – human, animal and something in between. They’re from the tomb of one of the great figures of Tang China, Liu Tingxun, general of the Zhongwu army, lieutenant of Henan and Huinan district and Imperial Privy Councillor, who died at the advanced age of 72 in 728.

Liu Tingxun tells us this, and a great deal more besides, in a glowing obituary that he commissioned for himself and which was buried along with his ceramic entourage. Together, figures and text give us an intriguing glimpse of China 1,300 years ago; but, above all, they are a shamelessly barefaced bid for everlasting admiration and applause.

Wanting to control your own reputation after death isn’t unknown today, as Anthony Howard, former Obituaries Editor at

The Times

, recalls:

I used to get lots of letters saying, ‘I do not seem to be getting any younger and I thought it might be helpful to let you have a few notes on my life.’ They were unbelievable. People’s self-conceit – saying things like, ‘Though a man of unusual charm’, and this kind of thing. I couldn’t believe that people would write this about themselves. Of course no one nowadays commissions their own obituary, and those that were sent always ended up straight in the wastepaper basket.

I used to rather boast that on the obits page of

The Times

, ‘We are writing the first version of the history of our generation,’ and that is what I think it ought to be. It certainly isn’t for the family or even the friends of the deceased.

The Tang obituaries were not for family and friends, either; but nor were they the first version of history for their generation. The intended audience for the obituary of Liu Tingxun was not earthly readers but the judges of the Underworld, who would recognize his rank and his abilities and award him the prestigious place among the dead that was his due.

Liu’s obituary tablet is a model of colourful self-praise, and he aims a great deal higher than Anthony Howard’s ‘man of unusual charm’. He tells us that his behaviour set a standard that was destined to cause a revolution in popular manners. In public life he was an exemplar of ‘benevolence, justice, statesmanship, modesty, loyalty, truthfulness and deference’, and his military skills were comparable to those of the fabled heroes of the past. In one great feat, we are assured, he beat off invading troops ‘as a man brushes flies from his nose’.

Liu Tingxun pursued his illustrious, if turbulent, career in the high days of the Tang Dynasty, which ran from 618 to 906. The Tang era represents for many Chinese a golden age of achievement, both at home and abroad, a time when this great outward-looking empire, along with the Abbasid Islamic Empire in the Middle East, created what was effectively a huge single market for luxury goods that ran from Morocco to Japan. You won’t find it written in many European histories, but these two giants, the Tang and the Abbasid empires, shaped and dominated the early medieval world. By contrast, when Liu Tingxun died in 728 and our tomb figures were created, western Europe was a remote and underdeveloped backwater, an unstable patchwork of small kingdoms and precarious urban communities. The Tang ruled a unified state that stretched from Korea in the north to Vietnam in the south and far west, along the Silk Road, by then well established, into central Asia. The power and the structure of this state – along with its enormous cultural confidence – are vividly embodied in Liu Tingxun’s ceramic tomb figures.

A gloriously lively troupe of ceramic tomb figures

The figures are arranged in six pairs, and all of them are of just three colours: amber-yellow, green and brown. It’s a two-by-two procession. At the front is a pair of monsters, dramatic half-human creatures with clownish grimaces, spikes on their heads, wings and hoofed legs. They are fabulous figures heading up the line, guardians to protect the tomb’s occupant. Behind them comes another pair of protectors, these ones entirely human in shape, and their appearance clearly owes a great deal to India. Next in line, contained and austere, and definitely Chinese, are two civil servants, who stand, arms politely folded, braced for their specific job – to draft and to present the case for Liu Tingxun to the judges of the Underworld. The last human figures in this procession are two little grooms, but they are completely overwhelmed by the magnificent beasts in their charge that come behind them. First, two splendid horses, just under a metre high, one cream splashed with yellow and green and the other entirely brown, and then, bringing up the rear, a wonderful couple of Bactrian camels, each with two humps, their heads thrown back as though whinnying. Liu Tingxun was setting off for the next world magnificently accompanied.

The horses and the camels in the entourage show that Liu Tingxun was, as you might expect, seriously rich, but they also underline Tang China’s close commercial and trading links with central Asia and the lands beyond, through the Silk Road. The ceramic horses almost certainly represent a prized new breed, tall and muscular, brought to China from the west along what was then one of the great trade routes of the world. And if the horses are the glamorous end of Silk Road traffic, the Bentleys or the Porsches, so to speak

,

the two Bactrian camels are the heavy-goods vehicles, each capable of carrying up to 120 kilograms (260 lbs) of high-value goods – silk, perfumes, medicines, spices – over vast stretches of inhospitable terrain.

Ceramic figures like these were made in huge numbers for about fifty years, around

AD

700, their sole purpose being to be placed in high-status tombs. They have been found all around the great Tang cities of north-west China where Liu Tingxun held office. The ancient Chinese believed you needed to have in the grave all the things that were essential to you in life. So the figures were just one element in the contents of Liu Tingxun’s tomb, which would also have contained sumptuous burial objects of silk and lacquer, silver and gold. While the animal and human statues would serve and entertain him, the supernatural guardian figures warded off malevolent spirits.

Between their manufacture and their entombment, the ceramic figures would have been displayed to the living only once, when they were carried in the funeral cortège. They were not intended to be seen again. Once in the tomb, they took up their unchanging positions around the coffin, and then the stone door was firmly closed for eternity. A Tang poet of the time, Zhang Yue, commented:

All who come and go follow this road,

But living and dead do not return together

Like so much else in eighth-century China, the production of ceramic figures like these was controlled by an official bureau, just one small part of the enormous civil service that powered the Tang state. Liu Tingxun, as a very high-ranking official in that state, brought two ceramic bureaucrats with him into his tomb, presumably to take care of the everlasting admin. Dr Oliver Moore has studied this elite bureaucratic class, which has become so synonymous with the Chinese state that we still refer to senior civil servants as mandarins:

Administration combined very old aristocratic families with what we could call new men. They were divided into various ministries – public works, the economy, a military board; and the largest of all was ritual. They would organize recurrent annual or monthly rituals, celebrations of the emperor’s birthday, or princes’ and princesses’ birthdays, seasonal observances – things like the ploughing rite, where the emperor would open the agricultural season by symbolically ploughing a field somewhere in the palace. There was a very small group, whose significance grew throughout the dynasty, who took examinations and competed for state degrees. Later on, this system became magnified, so that by the year 1000, you had something like 15,000 men coming to the capital to take exams, of whom only around 1,500 would get a degree. This is a system in which the largest number, well over 90 per cent, will fail – repeatedly for the whole of their lives – and at the same time this is a system which fostered loyalty to the dynasty – which is quite remarkable.

Liu Tingxun was a loyal servant of the dynasty, and the whole assemblage of his tomb – figures, animals and obituary text – sums up many aspects of Tang China at its zenith, showing the close link between the military and the civil administration, the orderly prosperity that allowed, and controlled, such sophisticated artistic production, and the confidence with which power was exercised both at home and abroad.

Pilgrims, Raiders and Traders

AD

800–1300

Medieval Europe was not isolated from Africa and Asia: warriors, pilgrims and merchants regularly crossed the continents, carrying with them goods and ideas. The Scandinavian Vikings travelled and traded from Greenland to Central Asia. In the Indian Ocean a vast maritime economic network connected Africa, the Middle East, India and China. Buddhism and Hinduism spread along these trade routes from India to Indonesia. Even the Crusades did not prevent commerce flourishing between Christian Europe and the Islamic world. In contrast, Japan, lying at the end of all the great Asian trade routes, chose to cut itself off, even from its neighbour, China, for the next 300 years.

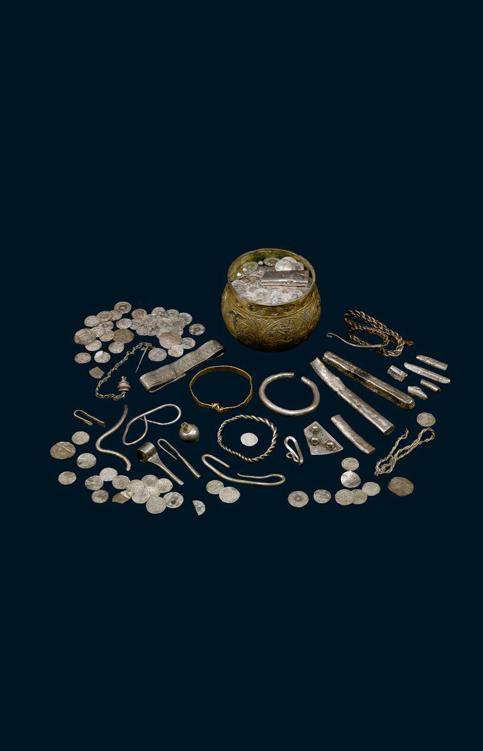

Vale of York Hoard

BURIED AROUND

AD

927

On the surface, everything is idyllic: a broad green field in Yorkshire, in the distance rolling hills, woods and a light morning mist. It’s the epitome of a peaceful, unchanging England, but scratch this surface or, more appropriately, wave a metal detector over it, and a different England emerges, a land of violence and panic, not at all secure behind its defending sea but terrifyingly vulnerable to invasion. It was in a field like this, 1,100 years ago, that a frightened man buried a great collection of silver, jewellery and coins that linked this part of England to what would then have seemed unimaginably distant parts of the world – to Russia, the Middle East and Asia. The man was a Viking and this was his treasure.

With the next five objects we’re sweeping across the huge expanse of Europe and Asia between the ninth and fourteenth centuries. We will be dealing with two great arcs of trade – one that begins in Iraq and Afghanistan, rises north into Russia and ends in Britain – and another in the south, spanning the Indian Ocean from Indonesia to Africa.