A History of the World in 100 Objects (43 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

There’s a lot of mystery still to unravel about this grim but gripping material. The Moche stopped making these horror-movie pots and indeed pretty much everything else in the seventh century – roughly at about the time of the Sutton Hoo ship burial (see

Chapter 47

). There are no written records to tell us why, but the best bet seems to be climate change. There were several decades of intense rain followed by a drought that upset the delicate ecology of their agriculture and wrecked much of the infrastructure and farmlands of the Moche state. People did not entirely abandon the area, but their skills seem to have been used above all for the building of fortresses, which suggests a world splintering in a desperate competition for diminishing natural resources. Whatever the cause, in the decades around

AD

600, the Moche state and civilization collapsed.

To most of us in Europe today, the Moche and other South American cultures are unfamiliar and unnerving. In part, that’s because they belong to a cultural tradition that followed a very different pattern from Africa, Asia and Europe; for thousands of years, the Americas had a separate parallel history of their own. But, as excavation unearths more of their story, we can see that they are caught in exactly the same predicaments as everybody else – harnessing nature and resources, avoiding famine, placating the gods, waging war – and, as everywhere else, they addressed these problems by trying to construct coherent and enduring states. In the Americas, as all over the world, these ignored histories are now being recovered to shape modern identities, as Steve Bourget details:

One of the fascinating things that I am looking at when I look at Peru today is that they are in the process of doing what also happens in Mexico, perhaps in Egypt, and eventually I would believe China, where these countries who have a great ancient past build their identity through this past and it becomes part of their present. So the past of Peru will be its future. And eventually the Moche will I think become a name just as much as the Maya or the Inca, or the Aztec for that matter. Eventually it will become part of the world legacy.

The more we look at these American civilizations the more we can see that their story is part of a coherent and strikingly similar worldwide pattern; a story that seems destined to acquire an ever greater modern political significance. And next we’re going to see what events of 1,300 years ago meant in contemporary Korea.

Korean Roof Tile

700–800

AD

If you use a mobile phone, drive a car or watch a television, the chances are that at least one of those objects will have been made in Korea. Korea is one of Asia’s ‘tiger’ economies, a provider of high technology to the world. We tend to think of it as a new player on the global stage – but that is not how Koreans see themselves, for Korea has always been pivotal in relations between China and Japan, and it has a long tradition of technological innovation. It was Korea, for example, that pioneered movable metal type, and it did it well before it was developed in Europe. Besides its technology, the other thing which everybody knows about Korea today is that, since the end of the Korean War in 1953, it has been bitterly divided between a communist north and a capitalist south.

This roof tile comes from Korea around the year 700, when the newly unified state was enjoying great prosperity. It is a moment in Korea’s history that is now read differently by north and south, but it is still central to any modern definition of Korean identity.

By 700, Korea was already a rich, urbanized country, a major trade player at the end of the famous Silk Road. But this object isn’t made of precious silk; it’s cheap clay – but clay that tells us a great deal about Korea’s ‘golden age’.

One of the fascinating things about this period is that on both edges of the Eurasian landmass similar political developments were under way. Tribes and little kingdoms were coalescing into larger units that would eventually become some of the nation states that we know today: England and Denmark on one side, Japan and Korea on the other. For all these countries, these were the critical centuries.

Lying between north-east China and Japan, the Korean peninsula was, like England at the same date, fragmented into competing kingdoms. In 668 the southernmost kingdom, Silla, with the backing of Tang Dynasty China – then, as now, the regional superpower – conquered its neighbours and imposed its rule from the far south to somewhere well north of what is now Pyongyang. It never controlled the far north (the border with modern China), but for the next 300 years the unified Silla kingdom ruled most of what is now Korea from its imperial capital in the south, Kyongju, a city splendidly adorned with grand new buildings. The ceramic roof tile in the British Museum comes from one of those new buildings, in this case a temple, and it tells us a great deal about the achievements and apprehensions of the young Silla state around the year 700.

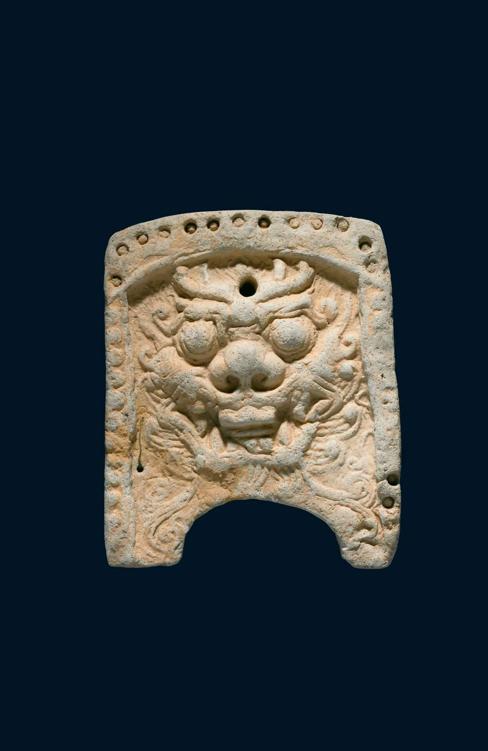

The tile is about the size of a large old-fashioned roof slate – just under 30 centimetres by 30 (12 inches by 12) – and it’s made of heavy cream-coloured clay. The top and the sides are edged with a roughly decorated border, and in the middle is a fearsome face looking straight out, with a squashed nose, bulging eyes, small horns and abundant whiskers. It looks like a cross between a Chinese dragon and a Pekinese dog. The tile is very similar to ones made in Tang China at the same time, but this is emphatically not a Chinese object. Unlike the broad grin of a Chinese dragon, the mouth here is small and aggressive – and the modelling of the tile has a rough vigour that is very un-Chinese.

It looks a bit like an oriental gargoyle – and that is pretty well what it was. It would have had a similar position to a gargoyle, high up on a temple or a grand house. The features of the face are quite rough, and it’s obvious that it has been made by pushing the wet clay into a fairly simple mould. This is clearly a mass-produced object, but that is why it’s so interesting; this is just one of tens of thousands of tiles designed to cover roofs that would once have been thatched but in prosperous Silla were now tiled with objects like this.

The Korean specialist Dr Jane Portal explains why the Silla wanted to build such a grand capital as Kyongju, and why they needed so many new houses:

The city of Kyongju was based on the Chinese capital Chang’an, which was at the time the biggest city in the world, and Kyongju developed hugely once Silla had unified most of the Korean peninsula. A lot of the aristocrats from the kingdoms which were defeated by Silla had to come and live in Kyongju, and they had magnificent houses with tiled roofs. This was a new thing, to have tiled roofs, so this tile would have been a sort of status symbol.

Tiles were sought after not only because they were expensive to make but, above all, because they didn’t catch fire like traditional thatch; burning thatch was the greatest physical threat to any ancient city. By contrast, a tiled city was a safe city, and so it is perfectly understandable that a ninth-century Korean commentator, singing the splendours of the city at the height of its prosperity, should dwell lyrically on its roofs:

The capital, Kyongju, consisted of 178,936 houses … There was a villa and pleasure garden for each of the four seasons, to which the aristocrats resorted. Houses with tiled roofs stood in rows in the capital, and not a thatched roof was to be seen. Gentle rain came with harmonious blessings and all the harvests were plentiful.

But this tile wasn’t intended merely to protect against the ‘gentle rain’. That was the job of the more prosaic, undecorated tiles covering the whole roof. Sitting at the decorated end of a ridge, glaring out across the city, our dragon tile was meant to ward off a teeming invisible army of hostile spirits and ghosts – protecting not just against the weather but against the forces of evil.

The dragon on our roof tile was, in a sense, just a humble foot soldier in the great battle of the spirits that was being perpetually fought out at roof level, high above the streets of Kyongju. It was only one of forty different classes of protective beings that formed a defensive shield against spirit missiles, which could be deployed at all times to protect the people and the state. But, at ground level, there were other threats: there were always potential rebels within the state – the aristocrats who had been forced to live in Kyongju, for example – and on the coast there were Japanese pirates. A dragon would provide security for the household, but every Silla king had to negotiate one great and ongoing political predicament that even dragon-faced house tiles could not deal with: how to maintain freedom of action in the looming shadow of his mighty neighbour, Tang China.

The Chinese had supported the Silla in their campaign to unify Korea, but only as an intended preliminary to China taking over the new kingdom itself, so the Silla king had to be both nimble and resolute in holding the Chinese emperor at bay while maintaining the political alliance. In cultural terms, the same subtle balancing act between dependence and autonomy has been going on for centuries and continues to this day to be a key element of Korean foreign policy.

In Korean history the united Silla kingdom, prosperous and secure at the end of the Silk Road, stands as one of the great periods of creativity and learning, a ‘golden age’ of architecture and literature, astronomy and mathematics. Fearsome dragon roof tiles like this one long continued to be a feature of the roofscape in Kyongju and beyond, and the legacy of the Silla is apparent in Korea even today, as Dr Choe Kwang-Shik, Director-General of the National Museum of Korea, tells us:

The cultural aspect of the roof tile still remains in Korean culture. If you go to the city of Kyongju now you can see in the streets that the patterns still remain on the road, for instance. So, in that aspect, the artefact has now become ancient, but it survives through the culture. In a sense, I think Koreans feel that it is an entity, as if it’s a mother figure. So in that sense Silla is one of the most important periods in Korean history.

But, in spite of surviving street patterns and strong cultural continuities, not everyone in Korea today will read the Silla legacy in the same way, or indeed claim the Silla as their mother culture. Jane Portal explains what it means now:

What Koreans think about Silla today depends on where they live. If they live in South Korea, the Silla represents this proud moment of repelling aggression from China, and it meant that the Korean peninsula could develop independently from China. But if they live in North Korea, they feel that Silla has been overemphasized historically, because actually Silla only unified the southern two thirds of the peninsula. What Silla means today depends on which side of the Demilitarized Zone you live.

Not least among the many questions at issue between North and South Korea today is what was really going on 1,300 years ago. As so often, how you read history depends on where you’re reading it from.

Silk Princess Painting

600–800

AD

Once upon a time, in the high and far off days of long ago, there was a beautiful princess who lived in the land of silk. One day her father, the emperor, told her she must marry the king of the distant land of jade. The jade king could not make silk, because the emperor kept the secret to himself. And so the princess decided to bring the gift of silk to her new people. She thought of a trick – she hid everything that was needed – the silk worms, the mulberry seeds – everything – in her royal headdress. She knew that her father’s guards would not dare to search her as she left for her new home. And that, my Best Beloved, is the story of how Khotan got its silk.