100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (13 page)

Read 100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die Online

Authors: Jon Weisman

30. Steve Garvey

There has never been another Steve Garvey. There has never been anyone to match his Popeye-sized forearms, his senatorial presence, and his 200-hit regimen straight out of Jack LaLanne. Never someone who was every bit the athleteâhe was a star college football player at Michigan State, after allâbut who wouldn't have seemed out of place heading to first base in briefcase, coat, and tie.

For Dodgers fans in the 1970s, underneath that metaphorical coat and tie was a big red

S

. Once Garvey moved over from third base to first and shed the need for his scattershot throwing arm, he became a legend straight out of baseball pulp fiction: a Dodger batboy and son of a team bus driver who rose up to become its conquering hero. He never missed a game. He could scoop an errant throw out of quicksand. Most of all, it always seemed, if you needed a hit, he got it for you. Starting in 1974, the year he became a write-in starter in fan balloting for the All-Star Game and later NL MVP, Garvey had at least 200 hits for six out of seven seasons, averaging 23 homers and 104 RBI. He was an All-Star every one of those seasons.

“He moves precisely, with a textbook stride, almost in slow motion,” wrote Pat Jordan in his renowned

Inside Sports

article on Garvey. “He is conscious of the way he runs and of the fact that he is being watched. His pumping arms are properly bent into L's at his sides, and held away from his body a bit, like wings, as if to keep his shirt from wrinkling. He resembles a man trotting to catch a bus in a new silk shirt on a hot day⦠His are the movements of a man with a single-focus concentration, a man for whom nothingârunning, picking up a ball, smilingâis natural and everything is learned.”

Separating his performance from his persona was nearly impossible. While still a player, Garvey got a junior high school named after him. It wasn't speculated, it was assumed that Garvey would run for public office after his playing career was over. Immortalization in bronze was invented for guys like Garvey.

“Steve Garvey is the only ballplayer I ever saw who, when he began to talk, you could almost feel the organ music and candlelight and incense,” Jim Murray wrote for the

Los Angeles Times

on December 23, 1982. “Who, when the choir struck up âAve Maria,' could turn to his date and murmur, âListen, darling, they're playing our song.'”

Murray wrote that column in the aftermath of Garvey's departure for San Diego and away from the Dodgers, who negotiated with Garvey but chose to go with touted minor league prospect Greg Brock rather than meet the demands of the soon-to-be 34-year-old. Garvey's consecutive game streak ended the following season at an NL record 1,207 games when he injured his thumb sliding into home, but he had one more World Series appearance and two more All-Star games with the Padres before retiring in 1987. So powerful was Garvey's presence in Southern California that even though he played only 645 games with San Diego, the team retired his number. That's something the Dodgers haven't done, because the Dodgers almost without exception require you to make it to Cooperstown first.

There has never been another Steve Garvey, in part because Steve Garvey wasn't really Steve Garvey. Time has not treated his legacy kindly. His ostensible political ambitions became the stuff of parody as revelations emerged of a troubled marriage, children fathered out of wedlock, and financial troubles. More relevantly for pure baseball fans, his on-field record has suffered as well. A closer look reveals that his on-base percentage was never all that high because of how rarely he walked (career high of 50). Not once was he the top hitter on a Dodger team, according to OPS+ or TAv. That's not at all to say he wasn't good; from 1974 through 1980, his TAv never fell below .283. But there was a time when the public considered Garvey to have the inside track to the Hall of Fame. The revelation that his numbers don't compare so well to other players, even on his own teamâRon Cey, Reggie Smith, and Davey Lopes all have arguably better statsâcombined with a certain

schadenfreude

among some about the decline of his public image, have left him on the outside looking in.

Garvey is best remembered if you place yourself back in the era in which he played. He was a winner, a rock, and he made you feel secure.

Â

Â

Â

31. Peanuts!

Playing catch with the greatest lefties in Dodgers history would have been something to remember. But while he might not be Sandy Koufax or Fernando Valenzuela, a catch with Roger Owens is a pretty great alternative.

Owens is the most famous peanut vendor in history, and for good reason. He came out to sling snacks at Dodgers games in their 1958 debut season at the Coliseum, working his way up the ballpark food chain starting when he was 15 years oldâfirst soft drinks, then ice creamâbefore cresting atop the exalted salted pinnacle. And then, like Raymond Chandler or Ray Charles, he reinvented the genre. Out of necessity when his path to a customer was blocked by some confused fans standing in front of him, Owens threw prudence and peanuts to the wind, flinging a bag behind his back and curving it around the clueless contingent right into the hands of his waiting patron.

Over time, Owens developed various circus throws such as under-the-legs and two-for-ones (two bags sent simultaneously to two different customers). He became first a legend locally and then nationally after he began appearing on

The Tonight Show

with Johnny Carson. With his infectious enthusiasm, Owens is the Magic Johnson (or, if you prefer, the Mickey Hatcher) of the eager-to-be-pleased Dodgers crowd.

And he's still thereâthough he won't be there forever. So while you still have the opportunity, get yourself some tickets in Owens' usual section on the left-field side of the Loge level, bring cash and an appetite, and call out “Peanuts!” And then prepare to have one of the quintessential Dodger Stadium experiences.

Â

Â

Â

The Cool-a-Coo

Of all the items that have ever been on the menu at Dodger Stadium, there might have been no departure more lamented than that of the Cool-a-Coo: a thick, generous dose of vanilla ice cream sandwiched between two oatmeal cookies, the entire amalgamation sealed in a chocolate covering. A similar dessert is the It's It, but is an It's It it? It isn't.

Cool-a-Coos vanished without warning from Dodger Stadium around the turn of the 21st century. Periodically a movement would begin to bring them back, to no avail.

But the new owners of the Dodgers, the Guggenheim Group, responded to the widely shared pleas of the fan base and negotiated its revival.

“Leo Politis, the South El Monte dairyman who made the original Cool-a-Coos, had sold his companyâand with it the Cool-a-Coo trademark,” wrote Bill Shaikin of the

Los Angeles Times

. “Sweety Novelty, the Monterey Park company that had acquired the trademark, did not make Cool-a-Coos.

“The Dodgers had to negotiate a contract with Sweety Novelty to manufacture the Cool-a-Coo and renegotiate deals with ice cream vendors who would now have a competitor at the concession stand.”

By September 2012, the Cool-a-Coo had made a triumphant return to Dodger Stadium.

32. Peter O'Malley

It was no accident that under the leadership of Peter O'Malley, the Dodgers had only six losing seasons in his nearly three decades as president, became the first team in the majors to break the 3 million barrier in season attendance, expanded their groundbreaking globalization of the game (a preoccupation that continued for O'Malley long after selling the Dodgers), and three times were the only sports franchise

Fortune

named as one of 1997's “100 Best Companies to work for in America.”

O'Malley could have chosen any field to work in. He could have forgone a work ethic. Instead, he showed constant diligence and vision. The Dodgers were lucky to have him.

He was a child when his father became a Dodgers vice president, and not quite a teenager when the family gained majority ownership of the team in 1950. In those days, after returning home from spring training in Florida, O'Malley would take one of Brooklyn's famous trolleys to Ebbets Field, mingle with the players, then cheer for the Dodgers from a seat behind the dugout before grabbing a ride home from Dad after the game.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Not quite a teenager when his family gained majority ownership of the Dodgers in 1950, Peter O'Malley (left) followed the successful steps of his father Walter (right). It was no accident that under the leadership of Peter O'Malley, the Dodgers had only six losing seasons in his nearly three decades as president.

Photo courtesy of www.walteromalley.com. All rights reserved.

Â

“Pete Reiser was a family favorite,” O'Malley recalled. “[Roy] Campanella was always talking to me about what's going on, fishing or something like that. Kirby Higbe, I identified with him for some reason. Rex Barney, who lived in Vero Beach later on after he played, was another family favorite. All the players, they were terrific. My memory is they were just nice to me, and I was never in their way.

“I remember washing Joe Black's car in Vero Beachâthat was the neatest thing. He gave me a dollar or whatever it was. I would say it was just a natural, comfortable feeling.”

Unsurprisingly, the Dodgers figured heavily in O'Malley's future. But what drew him most to a life in baseball wasn't a fascination with who was on the field, but what was happening off the field.

“I thought about law school when I was an undergraduate at Penn,” O'Malley said. “But then the move [of the Dodgers to Los Angeles] and the building of the stadium and all those issues convinced me, âDid I really want to go to school another couple of years?' So then I put aside the law school idea and just came and started working for the Dodgers.”

In 1962, O'Malley was named director of Dodgertown, then a January-April job, with the rest of the season spent rotating among the Dodgers' minor league teams. From 1965â66, O'Malley was president and general manager of the team's AAA franchise in Spokane, and then he came to Los Angeles in 1967 as vice president of stadium operations.

What laid the foundation for his ultimate success was not that he had the family name, but that he had a thirst for understanding the Dodgers business inside and out, alongside his interaction with people at every level.

“Looking back now, it was helpful because the people in the organizationâthe scouts, the managers, whoeverâthey all saw me summers along the way,” O'Malley said. “I didn't just arrive, whether they saw me in Vero Beach or a minor league city, or certainly those who came through Spokane. I met a lot of great people, not just in the organization, but umpires and managers of other teams in the [Pacific] Coast League in those days, owners of other teams, general managers, press people.”

Observers are often surprised if not skeptical when a young person takes over a ballclub, but O'Malley was an exception despite being only 32 when he started running the Dodgers in 1970. He had been around the franchise for so long that it was easy to accept him, and by the time he succeeded his father as president, he was in a comfort zone that enabled productive working relationships on all the off-field issues that so intrigued him when he was a Penn student.

Yet O'Malley never lost sight of on-field performance. When asked what his biggest challenge was as team president, he quickly mentioned when the Dodgers fell into last place in July 1979, and close behind recalled the devastating injury suffered by Pedro Guerrero, coming off his overpowering 1985 season at the end of spring training in 1986.

By those years, however, the Dodgers philosophyâone that could be summarized as patient decisivenessâhad become ingrained in him.

“Like a battleship,” O'Malley said, “rarely did we make a sharp right turn. It was usually an adjustmentâfine-tuning. We tried to make a decision with the long-term view of decisions you make every day. If we believed in the people who were there, and we did, and the strategy and the goal and everything else, you're going to have times you fall into last place or you get an injury.⦠âFire the manager, fire the pitching coach, fire the general manager, replace somebody else'âthat really didn't enter. We may have thought about it, but not seriously and for any length of time, because we believed in the people.”

Â

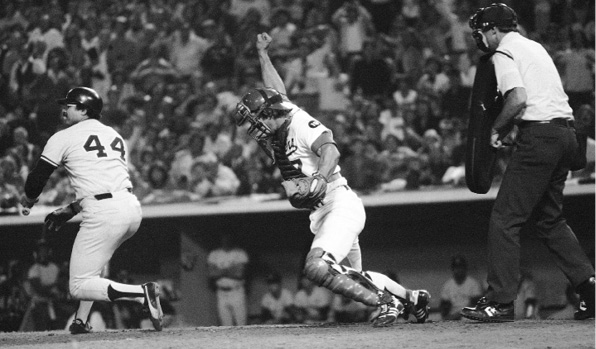

33. Down Goes Jackson

Perhaps even more than the pitch, people remember the reaction: Reggie Jackson untwisting himself from a swing that almost corkscrewed him into the ground. He grabbed his bat high on the barrel and violently thundered a furious curse.

David slew Goliath. Jack brought down the Giant. Bob Welchâall 21 babyfaced years of himâstruck out the Bronx Bomber on a 3â2 pitch in the ninth inning to save Game 2 of the 1978 World Series and bring on a deafening roar at Dodger Stadium.

The day the Series opened, rumors were spreading that fireballing Dodgers rookie Welch had an arm problem. Nonsense, insisted Tommy Lasorda. “Bob had a soreness in his side, down along his rib cage,” he told Scott Ostler of the

Los Angeles Times

. “Our trainer said he's fine.”

Apparently. Clinging to a 4â3 lead in the top of the ninth, the Dodgers sent out Terry Forster for his third inning of work. Yankees hero Bucky Dent opened the inning with a single to left field and moved to second on a groundout. A walk to Paul Blair put the go-ahead run on base, signaling that Forster had passed his expiration date.

Lasorda's do-or-die replacement had 24 career appearances, 11 in relief. The two batters he needed to get out, Thurman Munson and Jackson, had 465 career home runs between them, three of which were hit by Jackson in the last game of the previous year's World Series. Dodgers fans at the stadium and across the country waited for the roof to cave in.

Welch fed a strike in against Munson, who hit a sinking drive to right field that Reggie Smith caught at his knees.

Â

Â

Â

Powerhouse hitter Reggie Jackson is struck out by 21-year-old Bob Welch on a 3â2 pitch in the ninth inning. Welch saved Game 2 of the 1978 World Series and brought one of the most exhilarating victories over the Yankees ever imaginable.

Â

It was Jackson time. This wasn't just any slugger. This was the enemy personified, a man, though well-liked in his later years, considered perhaps the most egotistical, vilified ballplayer in the game.

Welch began by inducing Jackson to overswing and miss. With Drysdale-like flair, he then sent in a high, tight fastball that sent Jackson spinning into the dirt.

Jackson later told Earl Gustkey of the

Times

that he was expecting Welch to mix in some of his good offspeed pitches, but instead came three fastballs, each of which were fouled off. Then there was a fastball high and outside to even the count at 2â2.

After another foul ball, another high and outside fastball brought a full count. The runners would be moving. Short of another foul, this would be it.

As everyone sucked in their breath, in came the heat. Amped up, Jackson swung for the fencesânot the Dodger Stadium fences, but the fences all the way back in New York.

Only after Jackson missed the ball and nearly wrapped the bat around himself like a golf club, only through Jackson's rage, could Dodgers fans begin to comprehend what happened.

Jackson carried his fury into the dugout and clubhouse with him, pushing first a fan on his way to the dugout and then Yankees manager Bob Lemon once inside.

The only thing that could have made the event better for Dodgers fans would have been for them to have had longer to enjoy it. The Dodgers didn't win the World Series that year; they didn't win another game. Welch himself was the losing pitcher in Game 4, allowing a two-out, 10

th

-inning run in his third inning of work, and gave up a homer to Jackson in Game 6. But for a moment, the Dodgers and their fans enjoyed one of the most triumphant and exhilarating victories over the Yankees ever imaginable.

Hip To Be Tied

The Yankees were on the ropes. They had lost two of the first three games of the 1978 World Series and trailed 3â1 in the sixth inning of Game 4. New York had Reggie Jackson and Thurman Munson on first and second with one out, but Lou Piniella hit a sinking line drive to Dodger shortstop Bill Russell, who dropped it. Alertly, he stepped on second base to force Jackson out. Russell needed only to get the ball to Steve Garvey at first base to end the inning, but the action was thwarted. Jackson turned his hip into the ball, deflecting it toward the right-field stands, allowing Munson to score.

A furious debate ensuedâwith both sides accusing each other of intentionally mucking up the works (Did Russell intentionally drop the ball? Did Jackson intentionally interfere?)âbut the umpires let the play stand. The Yankees went on to beat the infuriated Dodgers in 10 innings 4â3 to even up the Series, then routed the Dodgers over Games 5 and 6.