100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (8 page)

Read 100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die Online

Authors: Jon Weisman

15. Walter Alston

For most, Walter Alston presents a stoic if upbeat memory; a solemn but avuncular gent surrounded by an aura of 2,040 victories as Dodgers manager from 1954â1976. The Dodgers won four World Series under Alston, including their first. In his second season in Brooklyn

and

his second season in Los Angeles, Alston piloted the team to World Series titles. Publicly, Alston projected the manner of the schoolteacher he used to be before his managerial career. A Hall of Famer with relatively little fame, his Cooperstown plaque calls him the “soft-spoken, low-profile organization man.”

Further review reveals a more complicated existence because the stately Alston, the man who worked under 23 one-year contracts, was steadily under the gun. He was second-guessed from the moment he was hired when a headline shouted “Walter Who?” He would only be thankful he didn't work in today's media-saturated age. In

The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers

, James studied Alston's career in detail. His style of managing, which at times involved extreme use of stolen bases, sacrifice bunts, pinch-hitters, pitching changes, defensive changes, intentional walks, and the hit-and-run would have come under even more intense scrutiny.

The attacks on Alston peaked in October 1962, when the Dodgers, who led the NL by four games with seven to play, surrendered the pennant in the final inning of a three-game playoff to the San Francisco Giants. Alston was blistered by fans, by the press, and by his coach (well, not really

his

coach, but a Dodger coach) Leo Durocher, who directly told reporters that he blamed Alston for the Dodgers' failure to make the World Series. Not only was Durocher the Dodgers manager from 1939â46 and also part of '48, and back as a coach in 1963, the team also hired the man Alston replaced, Charlie Dressen, in the front office.

Â

Â

Â

The path from obscure major league player to minor league manager to manager of the Dodgers eventually led Walter Alston directly to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1983. Alston, who played one game for the St. Louis Cardinals in the majors, was hired by Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley to skipper the team in the 1954 season, and he successfully remained at the post for 23 seasons, winning 2,040 games and world championships in 1955, 1959, 1963, and 1965.

Photo courtesy of www.walteromalley.com. All rights reserved.

Â

“Throughout his career in the majors,” Robert Creamer wrote in a 1963

Sports Illustrated

story, “Alston has been jeered, booed, mocked, hooted, taunted, derided, maligned, criticized, satirized, ridiculed, hung in effigy, and generally made out to be an incompetent boob holding his job only because of the incredible patience or shortsightedness of the Dodger front office.” Yet Alston not only survived, he won three pennants and two World Series in the next four seasons.

After the retirement of Sandy Koufax following the 1966 season, however, the best of times were over for Alston. In his 10 remaining seasons, the Dodgers made the postseason once.

In retrospect, Alston was anything but an emotionless presence with the Dodgers. Though he was renowned for not showing up his players in public, stories of fierce confrontations with his players, including Jackie Robinson and Don Newcombe, have become part of the backroom Alston legend. A chapter could be written on the Robinson-Alston dynamic, which began with Robinson's dim view of Alston's savvy and culminated with Alston's benching of the 36-year-old Robinson for Game 7 of the 1955 World Series. If there's a quintessential Alston story, it's the tale of him challenging any and all members of the '63 Dodgers to step off the team bus and fight him.

Alston's successor, Tommy Lasorda, quickly gained his reputation as the piss-and-vinegar manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers, but Alston, a man whose major league career was limited to one single strikeout, still burned. He may have burned on a low flame, but he burned.

Â

Â

Â

16. The Two Tommys

The Dodgers' biggest cheerleader had the mouth of a sailor. He was a Dodgers Blue carnival barker who could give you the greatest show on earth, even as his insides churned like a freight train.

It is no disservice to Tommy Lasorda to point out that he, like Walter Alston before him, was more coiled than his popular image (in this case, his famous exuberance) would suggest. Lasorda was born with aggression. In front of a camera, where the kids or the True Blue fans might see him, he was just a big ol' bear. In more private arenas, he was, well, a

big old bear.

Either way, he channeled that agita into crazy, indelible memories for the Dodgers, and you can hardly talk about the team without talking about him.

Lasorda spoiled for fights long before he won 1,599 regular season games, eight division titles, four league pennants, and two World Series as a Dodgers manager from the end of 1976 through the middle of 1996. After Wally Moon slashed Lasorda's leg in a home-plate collision during his first major league start with Brooklyn (as Lasorda wrote with David Fisher in

The Artful Dodger

), Lasorda had to be dragged away from staying in the game to pitch. Later with the Kansas City A's, Lasorda decided he was going to throw at every batter he saw in retaliation for the way New York Yankee pitcher Tom Sturdivant was knocking his teammates downâand he did, until Billy Martin charged out for a fight.

The methods at times might have bordered on madness, but never was there a doubtâpush; push himself, push the team, push the sport. Fatigue and fear were irrelevant. Twenty years passed between Lasorda's last major league game as a pitcher and his first major league game as a manager. Fight and spirit together got him there; one without the other would have stranded him.

That's how a man who was all business when it came to winning could also find time to dress Don Rickles up in a Dodgers uniform and send him out to the mound to pull Elias Sosa from a game after the Dodgers had clinched the NL West title in Lasorda's first season. If Lasorda heard a kid say he was a fan of another team, he could proselytize on behalf the Dodgers until heaven's blue gates opened. If Lasorda heard a reporter ask what he thought of Dave Kingman's three-homer performance, he could profanitize until the Apocalypse.

And so, as appealingly or menacingly cocksure Lasorda could be at times, when he asked his players for that something extra, they couldn't argue that he wasn't giving it himself. When it came to winning, you could never say a Lasorda opponent wanted it more.

This included strategy. When it came to the mind games of baseball, Lasorda was anything but passive. Not only was he always looking for opportunities to squeeze, steal, or hit-and-run, he was also looking for opportunities not to. Lasorda was all too happy to have home run hitters who could put runs on the board in a hurry. He just didn't always have them. He truly does deserve credit for his guidance in the improbable 1988 World Series upset over the A's. Between Kirk Gibson's homer and Orel Hershiser's pitching mastery were numerous decisions in which Lasorda out-maneuvered his Oakland rival, Tony LaRussaâand that could only be pulled off if his team were prepared to execute his maneuvers.

Not surprisingly, Lasorda did not go gently into that good night. It took a heart attack to wrestle the managerial reins away from him and, even after that, he remained a figure determined to be heard, whether as general manager or special advisor. In significant ways, Lasorda represents the evolution of the Dodgers from the relatively genteel organization of Koufax and Alston to the multifaceted behemoth they are today. Lasorda has a little bit of Brooklyn bum in him, which became a chip on his shoulder that sometimes could be self-defeating but every so often became the means to some very good ends.

“Nobody thought we could win the division!” Lasorda shouted in 1988's postgame celebration. “Nobody thought we could beat the mighty Mets! Nobody thought we could beat the team that won 104 games!

“But WE BELIEVED IT!”

Or at least two people did. The two-and-only Tommys.

Â

Â

Pitching to Jack Clark

Tommy Lasorda has not been criticized more for a single managerial decision than his choice to let Tom Niedenfuer pitch to Jack Clark with runners on second and third for St. Louis, two out in the top of the ninth inning of Game 6 of the 1985 NL Championship Series, and the Dodgers one out away from a 5â4 victory. Clark had an outstanding season (.322 TAv) for the Cardinals; the next Cardinals batter Andy Van Slyke was a rising talent at age 24, but not yet in Clark's class overall.

However, in the 1986 Baseball Abstract, Bill James makes a powerful argument in favor of Lasorda, noting that the Dodgers had a greater chance of preserving their lead by pitching to Clark with two on than loading the bases for Van Slyke, who had higher on-base and slugging percentages then Clark against right-handed pitching. Wrote James:

“If you walk Clark: 1) You're bringing a better hitter to the plate facing a right-hander, 2) You're allowing the Cardinals to tie the game with a walk, 3) You're using up the margin of error for the pitcher, and, 4) You're making an extra-base hit as damaging as a home run.

“Against this you have one advantageâthe fact that the veteran Clark has a well-deserved reputation as a clutch terror, while the young Van Slyke does not⦠Lasorda made the only reasonable move in the circumstances. It just didn't work.”

Nope, not at all, as Pedro Guerrero slamming his glove to the left-field ground can attest. Clark's homer over Guerrero's headâthe second game-winning blast off Niedenfuer in as many games for St. Louis, following Ozzie Smith's first career homer as a left-handed batter in Game 5âended the Series, the Cardinals winning four straight games after the Dodgers had taken a 2â0 lead.

One more option for the Dodgers would have been to walk Clark and bring in a left-hander like Jerry Reuss, who was warming up in the bullpen, to face a pinch-hitter for Van Slyke, but Reuss himself had been struggling, which made that matchup less desirable as well. It won't end the debate, but you can make a very strong case that Niedenfuer was the right guy, in the right situationâwith the wrong result.

17. Newk

I want to write a book about Don Newcombe. I want to because apparently no one has yet, and that seems incredible.

The Dodgers signed him out of the Negro Leagues before his 20

th

birthday, making him a teammate of Roy Campanella in Nashua, New Hampshire, in 1946. Three years later, Newcombe followed Campy and Jackie Robinson into the majors as the youngest black player of his time.

And like Robinson, Newk's impression was immediate. Shutting out Cincinnati in his first major league start, he pitched 244

1/3

innings with an ERA of 3.17 (130 ERA+) for the pennant-winning Dodgers, led the league in strikeouts per nine innings, won the NL Rookie of the Year award, and finished eighth in the voting for NL MVP (Robinson won). The Newcombe book-to-be would talk about him being a sensation.

The World Series began a run of dramatic late-season appearances for Newcombe. For example, in his first World Series startâthe black rookie taking the mound in Game 1, only 2

1/2

years after Robinson broke the color lineâhe took a scoreless duel into the ninth inning before allowing a homer to Tommy Henrich and losing 1â0. And then, following a solid second year (3.70 ERA, 111 ERA+), he gave up a three-run homer in the 10

th

inning of a game the Dodgers needed to win to force a playoff with Philadelphia. His next year he was worked to the bone, pitching often on rest of two days or less, including 16 innings in a doubleheader against those same Phillies. To cap his third year (3.28 ERA, 120 ERA+, NL-high 164 strikeouts), he found redemption with a critical shutout overâ¦what, the Phillies again?⦠followed by four shutout innings the next day to help get the Dodgers into a playoff with the Giants. And after just two more days of rest, another 8

1/3

innings in the final game of the playoffs, leaving with a two-run ninth-inning lead for Ralph Branca. The book would talk about the relentless heat of these moments.

Â

Â

Â

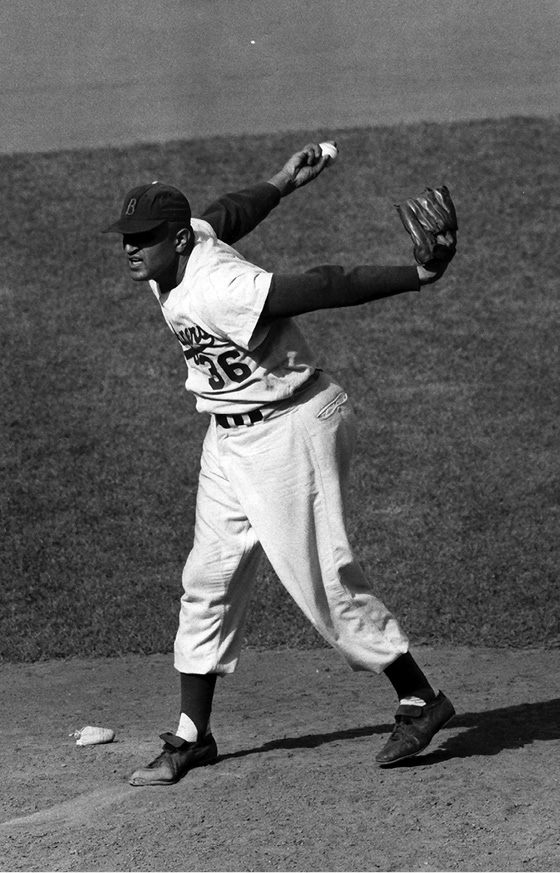

Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe is the only man to win the three major awards in baseballâthe Cy Young Award, Most Valuable Player, and Rookie of the Year. Newcombe was also the first African American to start a World Series game, in 1949.

Photo courtesy of www.walteromalley.com. All rights reserved.

Â

Newcombe didn't get another chance to pitch in the majors until 1954. In the interim, he was on military duty. The book would talk about his experiences as a black man in the service, and how that affected the rest of his life in and out of baseball.

After initially struggling during a partial season in '54, Newcombe fully flowered in the next two years, the ace pitcher of the '55 World Series champions (233

2/3

innings, 3.20 ERA, 128 ERA+)ânot to mention batting .359 in 117 at-bats with seven homers and a steal of home before winning the 1956 MVP and Cy Young Awards with a 3.06 ERA (132 ERA+). The book would talk about his reign as baseball's most dominant player.

And then the book would talk about his stumbles. About his battle with alcoholismâ¦

“In 1956 I was the best pitcher in baseball. Four years later, I was out of the major leagues,” he once said. “It must have been the drinking. When you're young, you can handle it, but the older you get, the more it bothers you.”

â¦And about how, for the second half of his lifeâhis life after baseballâhe maintained his sobriety and helped others do the same.

“I'm glad to be anywhere when I think about my life back then,” Newcombe told Ben Platt of MLB.com. “What I have done after my baseball career and being able to help people with their lives and getting their lives back on track and they become human beings againâmeans more to me than all the things I did in baseball.”

In my book-to-be, this would be put into context within the world Newcombe lived in, into the 21

st

century, and how that world evolved from his childhood and earliest playing days.

“We'd finally get a cab that would take us to a substandard hotel with no air-conditioning,” Newcombe is quoted as saying in Cal Fussman's

After Jackie: Pride, Prejudice and Baseball's Forgotten Heroes

, “while the white players went on their air-conditioned bus from Union Station to the Chase Hotel and didn't have to even so much as touch their shaving kits until they got to their rooms. Not one of themânot one of the white guys on the Brooklyn Dodgersâever got off that bus and said, âI'm going to go with Jackie, Don, and Roy just to see how they have to live, just to find out.'

“The first St. Louis hotel Jackie had to stay in back in 1947, then Roy in 1948, and me in 1949, was called the Princess. It was a slum. We moved to the Adams Hotel after a friend of ours bought it, but he couldn't afford air-conditioning. Many nights, we had to soak our sheets in ice water and put them on the bed just to get a little relief from the heat and humidity. Try that sometime. We kept our windows open even with the trolleys running up and down the street below, because in that heat, you needed to get some air.

“There we were, members of the great Brooklyn Dodgers.”

And there he is, the great Don Newcombe. If I don't write a book about him, someone should.

Â

Â

Â