100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (10 page)

Read 100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die Online

Authors: Jon Weisman

21. Campy

“The old gentleman's roundness, like the outward geniality, was deceptive. When Campanella took off his uniform, there was no fat. His arms were short and huge up toward the shoulder. Fat housewives have arms like that, but Campy's arms were sinew. His thighs bulged with muscle and his belly was swollen, but firm. He was a little sumo wrestler of a man, a giant scaled down rather than a midget fleshed out. He had grown up in a Philadelphia ghetto called Nicetown and he made you laugh with his stories of barnstorming through Venezuela with colored teams where [he said] you always had to play doubleheaders and meal money was fifty cents a day. But he would second-guess a manager and then deny what he had said. He accepted no criticism and his amiability was punctuated by brief combative outbursts. Still, it was difficult to resist him.⦔

â Roger Kahn,

The Boys of Summer

Â

The accident happened on the road. It was January 1958. The Brooklyn Dodgers were heading for Los Angeles. Jackie Robinson had just retired, but Roy Campanella, 36 years old, would be part of the caravan and had grown optimistic about the trip. Though he had suffered through consecutive subpar seasons for the first time since becoming a major leaguer in 1948, everyone had heard by now about the peculiar dimensions of the Dodgers' West Coast lodgings, the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Barely 250 feet to left field. Even at his age, even after hitting only 13 home runs in his final Brooklyn seasonâtwo after July 1âLos Angeles would be easy pickings for Campy.

Campanella's road was taking him to the Hall of Fame. His 10 Dodgers seasons produced three NL Most Valuable Player awards, eight All-Star seasons, 242 home runs, and a .291 TAvânumbers that were limited by how tardy his big-league promotion was, seeing as he had been playing pro ball since he was 15 years old with the Baltimore Elite Giants of the Negro Leagues. In 1953, his most astonishing season, he had an on-base percentage of .395 and slugging percentage of .611 (.320 TAv), hitting 41 homers and driving in 142 runs. In his painstaking research, historian Bill James determined that Campanella was the sport's greatest catcher at his peak, adding that he also probably had “the best throwing arm of his generation.”

“The managers would say to the young pitchers, âIf you shake Campy off, you better have a darn good reason,'” Dodger pitcher Carl Erskine said in an interview. “Everyone who played with him agrees, he would have been the first black manager in the big leagues if he hadn't had his accident, because he was that style of player and thinker.”

The stature of his accomplishments was underscored by the way his baseball mortality occasionally emerged, such as when 1954's injuries and slumps held him to 111 games, a .207 batting average, and 19 homers (.230 TAv). Although Campanella looked forward to Los Angeles, he had been building his life outside of baseball by the time the move was happening. Roy Campanella's Choice Wines and Liquors stood on the corner of Seventh and 134

th

in Harlem, and it was from there that Campanella was driving home at 1:30 in the morning, January 28, 1958.

The Chevy hit a patch of ice, and Roy Campanella skidded off the road. Paralyzed below the shoulders, his upper arms capable of only the slightest movement, Campanella struggled mightily. His playing days were over, but not his life.

He lived for almost as long after the accident as he had lived before it: 35 more years. He lived to see more than 93,000 fans pay stirring, heartbreaking tribute to him at that Coliseum field on the other side of the country. He published a book,

It's Good To Be Alive

. He completed his journey to the Hall of Fame in 1969. Peter O'Malley hired Campanella to be a catching instructor, and he tutored three generations of Dodger backstops in Steve Yeager and Joe Ferguson, Mike Scioscia, and Mike Piazza.

This was his painful yet rewarding path.

“I've accepted the chair,” he told Kahn. “My family has accepted it. My wife has made a wonderful home. I'm not wanting many things. Sure, I'd love to walk. Sure I would. But I'm not gonna worry myself to death because I can't. I've accepted the chair, and I've accepted my life.”

And Kahn reflected:

“He pushed the lever and the wheelchair started bearing the broken body and leaving me, and perhaps Roxie Campanella as well, to marvel at the vaulting human spirit, imprisoned yet free, in the noble wreckage of the athlete, in the dazzling palace of the man.”

Â

Â

Â

22. Sweep!

What if the Dodgers overwhelmed the Yankees in a World Series the same way Sandy Koufax typically overwhelmed NL batters? It's a question that Dodgers fans of either coast could hardly have dared ask.

But in 1963, it happened. The Dodgers not only beat the Yankees in the '63 Series, they swept them. They not only swept them, they never trailed in any game. And of course, it had to start with Koufax.

The left-hander was 27 years old at the time and about to win his first Cy Young Award. He began the World Series by striking out the first five Yankees he faced: Tony Kubek, Bobby Richardson, Tom Tresh, Mickey Mantle, and Roger Maris. After five innings, he had 11 Ks, and when pinch-hitter Harry Bright went down in the bottom of the ninth, Koufax set a World Series record with his 15

th

.

A good sign for the Dodgers was that although Koufax was supreme in his success, he wasn't alone. Johnny Roseboro hit a three-run homer off future Hall of Famer Whitey Ford to cap a four-run second inning, and second baseman Dick Tracewski knocked down a low liner by Clete Boyer to keep the Yankees from scoring in the fifth after two earlier singles broke up Koufax's no-hit bid. Though the Yankees got a two-run homer from Tresh in the eighth and a single in the ninth, Koufax was resilient enough to put them away.

Oh, and by the wayâKoufax didn't feel good.

“I felt a little weak,” he told the press afterward. “I just felt a little tired in general early in the game. Then I felt a little weak in the middle of the game. Then I got some of my strength back, but I was a little weak again at the end.”

Â

Â

Â

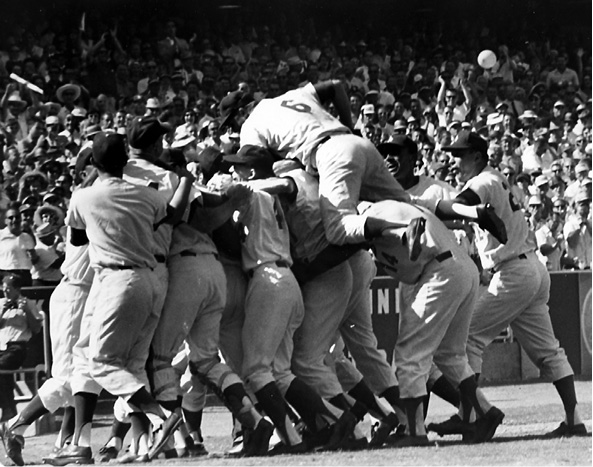

The celebration begins at Dodger Stadium after the Dodgers swept the New York Yankees in the 1963 World Series. Pitcher Sandy Koufax won two games in the four-game sweep, including the last game 2â1.

Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Dodgers, Inc. All rights reserved.

Â

Cautious in their optimism in the clubhouse after the initial victory, the Dodgers kept an all-business approach in Game 2. Willie Davis followed singles by Maury Wills and Jim Gilliam with a two-run double past a slipping Roger Maris in right field. Tommy Davis later added two triples, and Johnny Podres pitched 8

1/3

innings of shutout ball to send the Dodgers back to Los Angeles with a 4â1 victory and 2â0 series lead.

Despite getting only six hits in their next two games, the Dodgers closed out the series. Don Drysdale made a first-inning RBI single by Tommy Davis stand up for a 1â0 victory in Game 3. Then in Game 4, Frank Howard broke up a scoreless rematch between Koufax and Ford with the first-ever home run to the Loge level of Dodger Stadium. Mickey Mantle homered off Koufax in the seventh to give the Yankees their first tie of the postseason, but then came the final, fateful play of the Series. Gilliam grounded to Boyer at third base, but first baseman Joe Pepitone couldn't pick up the throw and let it get past him.

“I didn't see it,” Pepitone told John Hall of the

Los Angeles Times.

“It got lost in the shirts behind third base. It hit me on the side of the glove and the wrist and went on by.⦠Nothing like that happened to me all year.”

Gilliam zipped all the way to third base, and Willie Davis brought him home with a sacrifice fly for a 2â1 lead.

For those who didn't think the Yankees could ever be disposed of so easily, one play in the ninth gave pause. After Richardson singled off Koufax to open the inning, Tresh and Mantle struck out looking. But Elston Howard reached base on what was ruled an error by Tracewski catching a throw from Maury Wills, and suddenly the tying run was in scoring position. However, Koufax again was up to the task, inducing a 6â3 groundout from Hector Lopez.

Just like that, the Yankees, 104-game winners in the regular season, were swept away like yesteryear's dust, held to four runs in four games while striking out 37 times.

“For one of the few times since the electric light, the Bombers were forced to depart with a borrowed line that once belonged to the Dodgers,” Hall wrote. “Wait âtil next year.”

Â

Â

Dick Nen

Dick Nen's first major league at-bat came against St. Louis Cardinals ace Bob Gibson, which means that Dick Nen's first major league at-bat resulted in an out. The product of Banning High and Long Beach State had joined the major league roster of his now-local team earlier in the dayâSeptember 18, 1963âalthough Nen made his debut far from home and comfort. The host Cardinals led the Los Angeles Dodgers 5â1 in the top of the eighth behind four-hit, no-walk pitching by Gibson, and were six outs away from cutting the Dodgers' NL lead to two games with 11 days remaining in the regular season.

Nen did make solid contact against Gibson, lining out to center field, and if anything that might have been a sign that Gibson was tiringâletting a scrub get wood on him. Maury Wills and Jim Gilliam followed with singles, Wally Moon walked to load the bases, and then Tommy Davis singled to left field to cut the Cardinal lead in half. Bobby Shantz relieved Gibson and walked Frank Howard to load the bases, then gave up a sacrifice fly to Willie Davis. But a second reliever, Ron Taylor, retired Bill Skowron on a groundout, leaving the Dodgers down by a run. Nen stayed in the game at first as part of a triple switch, which meant that he would be due up again as the second batter of the ninth.

Dick Nen's second major league at-bat is still going on. When you mention unsung heroes in Dodgers history, Nen is one of the first names to enter the conversation because against Taylor, the left-handed Nen slugged a long drive over the right-field wall to tie the game. Dick Nen. Dick Nen! The Dodgers then rode Ron Perranoski's six innings of shutout relief to a 6â5, 13-inning victory, and ended up burying the Cardinals six games back.

Dick Nen's second major league hit would come nearly 21 months later with another team in another league and before a crowd of 4,294âat Dodger Stadium of all places, but as a member of the Washington Senators in a road game against the California Angels. Nen, the father of major league reliever Robb Nen, never had another moment like he had in St. Louis in his first major league game. Then again, most of us have never had a moment like that, period.

23. Piazza

The 1970s brought the Popeye arms of Steve Garvey and the 1980s had the majestic swing of Pedro Guerrero. But in the history of the Los Angeles Dodgers, there might not have been a hitter as startling, as eye-popping, as fall-back-in-your-seat-in-amazing as Mike Piazza.

His story as a Dodger was forever poisoned by his ungracious, day-the-music-died trade by the Dodgers to the Florida Marlins, shortly after the O'Malley family sold the team to News Corp.-owned Fox, and without the consent of general manager Fred Claire. Piazza's name evokes as much lament as wonder. Sandy Koufax retired young, but he retired as a Dodger. Garvey and Fernando Valenzuela gave Los Angeles their best years, Kirk Gibson his best moment. All had the time they needed to celebrate a World Series title.

Piazza was unique in Los Angeles history: a player firmly established as a future Hall of Famer that the Dodgers

aloha

'ed with several Cooperstown-caliber years remaining. That the hitter who replaced him, Gary Sheffield, was his measure with the bat (with a higher career Los Angeles Dodger OPS+ than Piazza) footnotes the shock but doesn't reduce it.

Piazza emerged from an obscurity quite differently from Valenzuela's, but from obscurity nonetheless. He began his professional career as an anecdote. He was the scion of a Tommy Lasorda boyhood chum named Vince Piazza, and the Dodgers selected him in the 62

nd

round of the June 1988 draft, after 1,389 other players and before only 43 others, as a favor. The ties between Lasorda and the elder Piazza were such that when Piazza briefly joined a group interested in purchasing the San Francisco Giants, reports stated Lasorda would leave Los Angeles and become manager of the Dodgers' archrivals.

Â

Â

Â

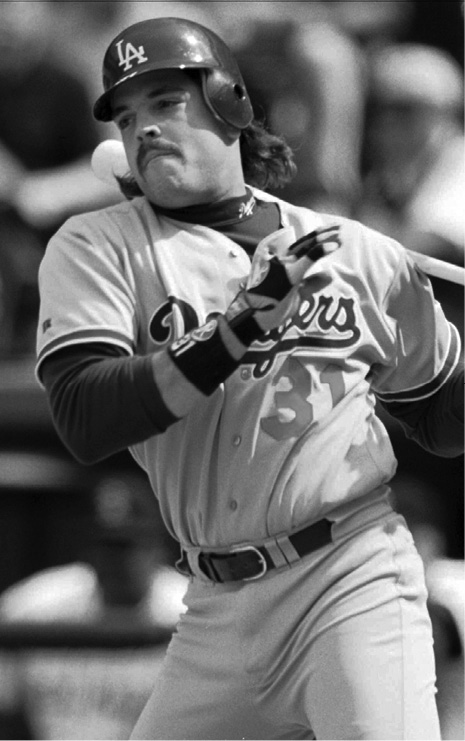

Mike Piazza may go down in history as the greatest hitting catcher of all time, but it's important to know that he first wore Dodger Blue. Piazza became the first Dodger ever to hit a ball out of Dodger Stadium.

Â

What few realized at the time was that the team had unwittingly acquired the ultimate late bloomer. When he was a teen, the Piazza family installed a batting cage in the backyard, and Mike developed a hitting stroke that even impressed Ted Williams, according to Maryann Hudson of the

Los Angeles Times

. That nascent skill was hidden by how unrefined the rest of his game was. Piazza went undrafted out of high school, and ended up walking on at the University of Miami before transferring to Miami-Dade Community College.

After the Dodgers drafted him, following Lasorda's encouragement to move from first base to catcher, he became the first U.S. ballplayer to attend the Dodgers' Dominican Republic academy. “After more than two months, he had lost 25 pounds and suffered prolonged bouts of homesickness,” wrote Bill Plaschke in the

Times. “

But he learned to catch.”

He got a September trial at the end of the Dodgers' lost 1992 season, going 3-for-3 with a walk in his major league debut. He presented such impressive potential that the Dodgers allowed 13-year vet Mike Scioscia to sign with San Diego. “He hits the ball so hard,” wrote Hudson during spring training 1993, “that even his teammates crowd around the cage to watch him during batting practice.”

So true. It's no surprise that Piazza became the first Dodger ever to hit a ball out of Dodger Stadium. He lashed the ball; he sledgehammered it. In his first full season, he set what was then a Los Angeles Dodgers record with 35 home runs, including two in the final game of the year to help knock the Giants out of a playoff berth. In a 1995 season limited by injury, he hit 32 in 112 games. In 1996, he broke his team record by hitting 36. A year later, he topped himself again with 40.

Never an all-or-nothing hitter, that '97 season represented the full flowering of Piazza as a batsman. He developed the plate discipline (or the awe of opposing pitchers) that gave him the greatest offensive season in Los Angeles Dodgers history. He batted .362 with a .431 on-base percentage and .638 slugging percentage, a 185 OPS+ never approached for the previous 40 years or the following 10 (except for Manny Ramirez's two months in 2008).

Thirty-seven games later, Piazza was wearing a Florida Marlins uniform. In 726 games as a Dodger, he batted .331, on-based .394 and slugged .572, hitting 177 homers, and averaging one every four games. That wasn't even the halfway point of the back of his baseball card. In his post-Dodgers career, he added 1,186 games and 250 homers, at a .293/.365/.528 pace. Overall, he will go down in history as the greatest hitting catcher of all time.

It wasn't that the Dodgers were robbed of talent. Sheffield was a tremendous hitter. It was that the Dodgers were robbed of half of a great novel. They got the

War

without the

Peace

.

That first half was a heck of a read, though.

Â

Â

Â