100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (16 page)

Read 100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die Online

Authors: Jon Weisman

40. “The Best Hitter God Has Made in a Long Time”

After each home run he hit, Pedro Guerrero would look up in the stands and wag his index finger like a little puppet to his wife. In June 1985, the puppet show practically became a daily event.

Though in his retirement Guerrero would generate a small bit of infamy for being acquitted on a drug conspiracy charge with a defense that his IQ was not high enough for him to have masterminded the deal, Pedro Guerrero was the thinking Dodgers fan's hitting hero in the 20

th

century. The genuine article.

Immediately before Guerrero, there was Steve Garvey and Ron Cey and Davey Lopes. There was Dusty Baker and the forever underrated Reggie Smith.

None of them quite swung the laser that Guerrero did.

“Pedro is the best hitter God has made in a long time,” wrote Bill James in the 1985 edition of his

Baseball Abstract

. “His stats, for Dodger Stadium, are as good as [George] Brett's or [Jim] Rice's or anybody else's in their own context.”

Born in 1956 in the Dominican Republic, Guerrero first reached the big leagues in 1978, Total Averaged .310 in 1980 while playing six positions, and shared the World Series MVP award with Cey and Steve Yeager in 1981. Always productive, Guerrero somehow topped himself in June 1985.

Â

Â

Â

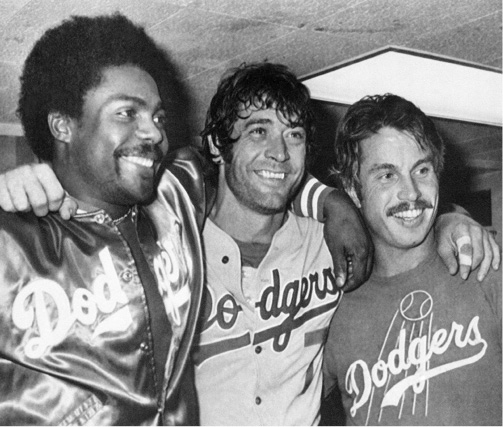

In June 1985, Pedro Guerrero (on left, shown here with catcher Steve Yeager and third baseman Ron Cey) slammed 15 home runs in one month, breaking the home-run record for June and second for all-time in a month. Guerrero slugged .860 and in the following month, reached base in 14 straight plate appearances.

Â

On the first day of the month, he hit a home run. Again on the fourth day, the seventh day, the eighth day. In a four-game stretch from June 10â16 (interrupted by rainouts), he hit five homers. He hit his 10

th

homer of the month on June 19, then homered again in four of his next six games.

He spent three days in pursuit of a 15

th

blast of the month, which at the time would give him the major league record for most homers in June and second-most for most homers in any month, behind Rudy York. In his final at-bat of a June 30 Sunday afternoon game at Dodger Stadium, Guerrero did itâwinning the game to boot with his two-run dinger.

For the month, Guerrero averaged nearly a base per plate appearance (including walks) and slugged .860. And he wasn't doneâat one point the following month, he reached base in 14 straight plate appearances. He finished the year with a .422 on-base percentage, .577 slugging percentage, and .360 TAv.

The Dodgers won the NL West in 1985 and had every expectation of repeating in 1986. But just before the end of spring training, Guerrero ruptured a tendon in his left knee. He came back strong in 1987 with a 154 OPS+, but he was traded in the middle of the Dodgers' championship season in 1988 for John Tudor. Still, for his Los Angeles Dodger career, Guerrero ranks fourth all-time in OPS+. In the 1980s, Guerrero was as good as there was.

Â

Â

Â

41. Steady as She Goes

The loneliest job in the world this side of the Maytag repairman used to be that of Dodger human resources director. With only three general managers, two managers, and one Vin Scully employed during a four-decade stretch under O'Malley team ownership, Rip Van Winkle could have applied for a position and had a full nap waiting to hear the news.

Even after the dawn of free agency, even after years of the Garvey-Lopes-Russell-Cey infield gave way to more frequent change, stability remained the Dodgers' calling card well into the 1990s. And even when names did change, there was continuity.

“There was a process, a system in place that didn't have to be reinvented every year or two years and yet was enhanced with improvement year by year,” former Dodger GM Fred Claire said in an interview.

“For example, if you take the critical role of pitching coach, at the time that I was fired, Glenn Gregson had been our pitching coachânot a name well known,” Claire recalled. “He had started with us in Bakersfield in 1990. He replaced Dave Wallace, who came out of our system. Dave Wallace replaced Ron Perranoski, who came out of our system. Ron Perranoski replaced Red Adams, who came out of our system.... And if you look at all of this depth, that's not a rarity. That was the system. You can look at hitting coaches, you can look at field coordinator.

“And this applies not only to the major league level, but to the minor league level and to the scouting. This system had gone back literally to [Branch] Rickey days.”

The flip side of stability and continuity, of course, is becoming so stuck in a rut, so addicted to formula, that you miss bolder chances for improvement and innovation. Surely, that happened to the Dodgers at times. But it wasn't as if changes never took place. In the meantime, the team's solid foundation worked as a security blanket, allowing the Dodgers to take a long-term view and, for the most part, avoid desperate, self-destructive decisions.

When Dodgers fans look back at life under the O'Malleys, they rarely lament the moves that weren't made, but rather those that were: namely, letting beloved team figures go. Stability wasn't a panacea for the Dodgers, but as a fail-safe, it was effective. Continuity with the humility to consider change seems like a pretty good model.

Â

Â

Foundation

As the 2008 regular season drew to a close, the Dodgers held their annual ceremony at Dodger Stadium honoring longtime employees. More than 50 had worked for at least a quarter-century at the ballpark. Some are well-known, such as Vin Scully, Tommy Lasorda, or Jamie JarrÃn, but many more toil behind the scenes in anonymity: ushers, grounds crew, accountants, vendors, ticket takers, batting practice pitchers, and administrative assistants. It's worth taking a moment to appreciate those who work, often from morning until well after the game ends, year after year.

42. 1980âThe Final Weekend

In the 1980 season, from April 26 on, the Dodgers never lagged nor led by more than three games in a taut NL West. Tied for first place with Houston on September 24 with 10 games remaining, they suffered back-to-back 3â2 defeats to San Francisco and San Diego to fall two back. A week later, yet another 3â2 loss to the Giants put the Dodgers three back with three to play. The saving grace was that the Dodgers would be hosting Houston for the final three games of the regular season. But facing starting pitchers Ken Forsch (3.20 ERA), Nolan Ryan (3.35), and Vern Ruhle (2.37), the Dodgers faced a tall task.

What followed was one of the most memorable series in franchise history.

On Friday, October 3, Alan Ashby's sacrifice fly off Dodger starter Don Sutton gave Houston a 2â1 lead and put the Astros within two innings of clinching the division. Forsch got four consecutive groundouts to move Houston within two outs of the title. But with one out in the ninth, Rick Monday singled, and Dusty Baker reached on an error by second baseman and ex-Dodger Rafael Landestoy. Steve Garvey flied out, but down to their final at-bat before elimination, Ron Cey singled to center field, scoring pinch-runner Rudy Law. Forsch retired Pedro Guerrero to send the game into extra innings.

Fernando Valenzuela, in his eighth career game, retired the side in order in the 10

th

inning, his second inning of work. And then, in the bottom of the 10

th

, Joe Ferguson homered off Forsch, frenzying the crowd. Flinging his helmet like a frisbee as he crossed home, Ferguson kept the Dodgers alive for one more day. Finally, an important 3â2 game went the Dodgers' way.

On Saturday, Garvey's fourth-inning homer off Ryan broke a 1â1 tie, and Dodger starter Jerry Reuss made the advantage stand up, though not without some nail-biters. With two out in the top of the ninth, Reuss gave up singles to Cesar Cedeno and Art Howe, putting the tying run at third base. But Gary Woods, with a .396 on-base percentage, grounded out, and just like that, the Dodgers were playing for a tie on Sunday.

For the second time in three days, Houston moved within six outs of clinching the division. The Astros scored two early runs off Burt Hooton, who was removed by desperate Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda after recording only three outs in eight batters. Bobby Castillo gave up a third run in the fourth inning to put Los Angeles behind by three. Pitching two shutout innings for the second time in three days, Valenzuela kept the Astros at bay while the Dodgers got on the scoreboard with a fifth-inning RBI single by Davey Lopes.

In the bottom of the seventh, with runners at second and third, 42-year-old Manny Mota pinch-hit for the 19-year-old Valenzuela. Mota's pinch singleâthe final hit of the beloved Dodger's careerâdrove in Guerrero to cut the lead to 3â2. But Baker later fouled out with the bases loaded, and the Dodgers entered the eighth inning still down by a run.

NL Rookie of the Year Steve Howe retired the Astros in the eighth. Then, once more, the Astros made a pivotal errorâEnos Cabell allowed Garvey to reach baseâand the next batter, Cey, sent Dodgers fans into delirium with a homer.

When Howe allowed two singles in the top of the ninth, Lasorda continued to manage within an inch of his life. He brought in Sutton, who had gone eight innings fewer than 48 hours earlier, to get the final out. Denny Walling grounded to Lopes, and the NL West season had gone overtime.

Lasorda chose Dave Goltz, a tremendous disappointment in 1980 after signing a free agent contract, to start the winner-take-all 163

rd

game. Subsequent legend has insisted Lasorda made a mistake hereâthat he should have instead started Valenzuela, who had yet to allow an earned run in his career and would go on to pitch that Opening Day shutout in 1981 to kick off Fernandomania. But, as indicated earlier, Valenzuela had pitched four innings in the past three days already, eliminating him from starting contention. Hooton had just been knocked out, Sutton and Reuss weren't available. Rick Sutcliffe, the 1979 NL Rookie of the Year, had been banished to the pen after posting a 7.51 ERA as a starting pitcher in 1980.

Though a disappointment, Goltz had a 2.56 ERA in 38

2/3

innings since September 2. It might have been his luckiest stretch of the season, but it made Goltz the best available option.

In the end, Lasorda might have been better off coming out of retirement to make the start himself. Two Dodger errors helped put Goltz in a 2â0 hole in the first inning, and a two-run homer by Howe made it 4â0 in the third. Pitching in relief in the fourth, Sutcliffe surrendered three runs, and the Dodgers were done.

It was a deflating end to an incredible weekend. If the Dodgers had completed that four-game sweep to the title, it would have been a topâ10 all-time moment. As it is, even in defeat, it was a weekend that the Dodgers could not forget.

Â

Â

Â

43. Black and Blue and Purple Heart

This is the what-might-have-been story of the greatest player in Dodgers history. This is the bone-breaking, heartbreaking, hide-your-eyes story of the man for whom baseball was a playground and a brick wall.

The should've been greatest player in Dodgers history was named Pete Reiser, and he began once upon a 1939 by reaching base the first 12 times he came to bat in spring training, the month of his 20

th

birthday. Having made an unwritten agreement with Branch Rickey, then running the Cardinals, to sell Reiser back to his original team in St. Louis (Reiser was one of numerous minor leaguers Kenesaw Mountain Landis set free after calling into question the Cardinals' minor league operations), Dodger general manager Larry MacPhail hid the young outfielder in the minors with the team in Elmira.

Reiser spent three months of that season with his right arm in a cast, teaching himself to throw left-handed so that he could get back on the field sooner. And after he did, after his potential became obvious to everyone in Dodgerland, MacPhail found it impossible to fulfill his end of the secret bargain with the Cards.

The tornado came in 1941. Twenty-two years old, reaching base at a .406 clip, Reiser led the league in total bases (299 in 137 games), batting average (.343), slugging percentage (.558), doubles (39, tied with Johnny Mize), triples (17), OPS+ (165), and, forebodingly, hit-by-pitches (11). From the outset of his career, his injuries warranted a revolving door at the hospitalâas quickly after a beanball sent Reiser to the hospital, he'd plot his escape. W.C. Heinz, in his incomparable if loose-with-the-details story on Reiser, chronicled how Dodgers manager Leo Durocher would have him put on his uniform even though he wasn't supposed to playâjust to buck up the spirit of his teammatesâthen find it impossible not to use him off the bench.

Twenty-two years old in 1941, a hero and a casualty, an emblem just in time for war.

Reiser had one more season before joining the service, and that was the season that did him in. July 19, 1942, bottom of the 11

th

inning, score tied at 6â6 in St. Louis. Enos Slaughter hits one over his head. “Out in center field, Pete Reiser tore back at top speed,” wrote Tommy Holmes for

The Sporting News.

“He caught the ball a split second before he crashed into the concrete wall. The round, white thing spurted out of his glove. Reiser picked himself off the turf and staggered after it. He threw it and a double relay made the play at the plate reasonably close.

“That was the ballgame and there wasn't anything to do except go out and pick up the pieces.”

He had again been leading the NL, batting .379. He was back at the hospitalâand then, just as soon out of itâon a train to Pittsburgh and back in action. Holmes wrote “just six days after he had rammed his skull against the center field wall at Sportsman's Park.”

Over the next three seasons, Reiser played ball for different squads in the Army, challenging the common-sense notion that the ballfield was safer than the battlefield. He made it back to Brooklyn for the 1946 season, stealing a league-high 34 basesâincluding seven swipes of home, an NL record. He finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting, despite missing 34 games. “Twice,” recalled Harold C. Burr of

The Sporting News,

“he went headlong into the concrete at Ebbets Field and near the end of the season broke his ankle, sliding back to first base against the Phillies, and watched the playoffs with the Cardinals with the limb in a plaster cast.”

In 1947, on the fourth of June occurred another brutal collision with a wall. “Mercifully, he came out of this one, groggy and mumbling, but without a cracked skull,” reported Burr. “Pete was taken to the Swedish Hospital with a wicked V-shaped cut along his hairline.... âI don't even remember making the catch,' Pete said in the dressing room, smoking a cigarette while awaiting the arrival of the hospital ambulance.” Within a week, Rickey, by this time reunited with his prize prospect in Brooklyn, put into work plans to rubberize the Ebbets Field outfield wall.

“The boy the fates delight in using as their plaything” was out for six weeks and still enduring dizzy spells when the Dodgers went into the 1947 Series against the Yankees. In Game 2, he misplayed three balls into triples, though he blamed it on the shadows at the Bronx ballpark. In the third game, he walked in the first inning, got the steal sign and, when he went into second, felt his right ankle snap, though no fracture was reported.

And yet, when Bill Bevens was in the ninth inning of his no-hit bid the next day, and Reiser pinch-hit, Yankees manager Bucky Harris walked him intentionally. He was still Pete Reiser, broken shell and all.

One more season in a Brooklyn uniform. Thirty more hits. The sensation at age 20 was traded away just before turning 30, struggling through four more campaigns before walking away from the playing field while he barely still could. He finished his major league career with a 128 career OPS+, but only 786 hits. Pete Reiser, the broken legend, the greatest Dodger that never was.

Â

Â

Roberto Clemente: What Happened?

Al Campanis saw a teenage Roberto Clemente while scouting for the Dodgers at a Puerto Rico tryout camp in 1952, and in February 1954, Brooklyn outbid the New York Giants and signed the 19-year-old to a $5,000 contract with a $10,000 bonus. However, the bonus required the Dodgers keep him on the major league roster or risk losing him at season's end. The Dodgers took the chance, assigning Clemente to their minor league affiliate in Montreal.

Clemente, writes Stew Thornley in his thoroughly researched piece for the Society of American Baseball Research's Baseball Biography Project, played only intermittently and not particularly well for Montreal much of the year, finishing with a .257 batting average and two home runs in 87 games, though he began to have success against lefties come July. And people recognized the talent. “You knew he was going to play in the big leagues,” teammate Jack Cassini said. “He had a great arm and he could run.”

The 1954 Rule 5 Draft, held in November, marked the occasion for major league teams to draft eligible minor leaguers from other organizations. Each franchise could lose at most one player, and the Pittsburgh Piratesâwho had the worst record in baseballâwould draft first. The Pirates were now Branch Rickey's club, and though he was still friendly with his replacement in Brooklyn, Buzzie Bavasi, he chose Clemente.

The rules of the time were simply not set up to allow the Dodgers to nurture a highly prized, highly priced minor leaguer without the peril of losing him. The right fielder's legendary, 3,000-hit, 266-assist Hall of Fame career would begin in Pittsburgh in 1955, and end only with his tragic death in a plane crash on an aid mission to Nicaraguan earthquake victims on December 31, 1972.