Resident Readiness General Surgery (75 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

If there is widespread cellulitis or signs of systemic infection, the use of empiric intravenous antibiotics should be strongly considered. Empiric antibiotics should target the microorganisms most likely responsible for the infection, yet not be so narrow as to miss other less likely but still potential pathogens. If broad-spectrum antibiotics are initiated, it is important to obtain a culture and Gram stain of the wound prior to the initiation of antibiotic therapy so that coverage can be tailored to the sensitivities as soon as they become available.

6.

Seroma formation can lead to delays in healing and increase the risk of wound infection. The best method for managing seromas is prevention. This can be done by leaving closed-suction drains in surgical wounds at particular risk for seroma formation. By placing drains in the at-risk wounds, serous fluid passes into the drain, where it travels to a suction device (ie, a bulb). Drawing this fluid out of the body prevents its accumulation in the potential space created through tissue resection, thus preventing seroma formation. It is important that these drains are not pulled prematurely, as a seroma may subsequently develop. Applying pressure dressings to at-risk wounds is another technique to decrease the likelihood of seroma formation. This works by compressing damaged lymphatic channels and minimizing leakage of lymphatic fluid.

Once a seroma has formed, there are several management options available. If the seroma is small and not infected, one can simply observe it and wait for reabsorption. Another option is aspirating with a needle and a syringe. The benefit to the latter is that this is both diagnostic and therapeutic. Aspiration should be done under sterile conditions in order to avoid introducing any pathogens into an uninfected fluid collection. Aspiration may be repeated, but after several aspirations, the wound should be reopened and allowed to heal by secondary intention. If drainage is heavy, it may be necessary to take the patient to the operating room to explore the wound and ligate any leaking lymphatic channels. As with any superficial wound infection, when seromas become infected they should be reopened and allowed to heal by secondary intention. An example you are likely to encounter on a vascular surgery rotation, a seroma that develops following a dissection of the groin and subsequently becomes infected.

The management of postoperative wound hematomas is similar to seromas. Small hematomas can be observed and will likely reabsorb. Larger hematomas may need sterile aspiration. If they recur or show signs of expansion, the patient may need to be taken back to the operating room to look for any ongoing bleeding. Importantly, decisions regarding observing or draining seromas and hematomas should always involve discussions with senior members of the surgical team.

7.

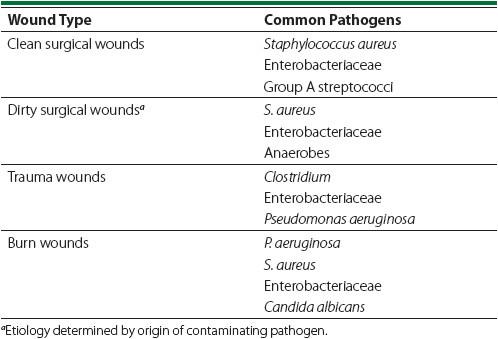

In general, clean cases are associated with infections due to skin flora. Infections after a clean-contaminated case can be due to both skin flora and the flora associated with the viscera on which you operated. Contaminated and dirty wounds are almost always infected by pathogens from the source of contamination. In this patient the most likely culprit is

Staphylococcus aureus

. See

Table 57-2

for an abbreviated list of the most common pathogens for different types of wounds.

Table 57-2.

The Most Common Inciting Pathogens for Wound Infections Based on Wound Classification

TIPS TO REMEMBER

Wounds are classified into four major groups: clean, clean-contaminated, contaminated, and dirty/infected—each with a progressively higher risk of SSI.

The presence of a seroma or hematoma increases the risk for developing postoperative wound infections.

Ultrasound may be useful in identifying or characterizing superficial or deep incisional SSIs. CT may be useful in identifying organ/space SSIs.

The key to managing postoperative wound infections is to assess the wound, consider initiating antibiotics, and consider opening the wound to permit drainage of infected fluid.

When persistent drainage of serous fluid from an abdominal wound is appreciated, fascial dehiscence must be considered. This warrants evaluation by a senior member of the surgical team.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.

An exploratory laparotomy is performed for a gunshot wound to the abdomen. The patient is found to have an enterotomy with spillage of fecal contents. What is the class of the wound?

A. Clean

B. Clean-contaminated

C. Contaminated

D. Dirty/infected

2.

Which of the following are risk factors for the development of postoperative wound infections?

A. Seromas

B. Hematomas

C. Gross spillage of GI tract contents during surgery

D. B and C

E. A, B, and C

3.

A patient who underwent a laparoscopic appendectomy for perforated appendicitis presents to the ED on POD #8 with abdominal pain, distention, and no bowel movements or flatus for 2 days. He had been having normal bowel movements since POD #2. He has had no nausea or vomiting. He continues to have lingering RLQ abdominal pain and is found to have a mild leukocytosis. This presentation is most consistent with which of the following?

A. A normal postoperative course

B. Adhesive small bowel obstruction

C. Urinary tract infection

D. Organ/space SSI

E. Stump appendicitis

Answers

1.

C

. Contaminated surgical wounds are defined as those resulting from a case where there is poor sterility secondary to gross spillage from the GI tract, GU

tract, or respiratory tract or by the presence of foreign debris—and without an established infection. Although this patient has fecal contamination, it is an acute process and is unlikely to have resulted in surrounding soft tissue infection or abscess formation.

2.

E

. Seromas, hematomas, and contaminated wounds are all risk factors for postoperative wound infection. Patients with contaminated wounds have a 20% to 25% risk for developing a postoperative wound infection.

3.

D

. Organ/space SSIs involve organs or spaces that were opened at the time of surgery. In perforated appendicitis, patients are at a particularly high risk for SSIs, given the local (or sometimes even diffuse) contamination of the normally sterile peritoneal cavity. An abscess is the likely diagnosis, manifested by recurrent ileus, abdominal tenderness, and a leukocytosis. Adhesive SBO is less likely than organ/space infections as it often takes weeks for adhesions to develop. Focal RLQ tenderness is not characteristic of UTIs. Stump appendicitis is the case in which residual appendix tissue remains unresected and becomes inflamed. Although this is possible, it is very rare and quite unlikely.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Ryan KJ, Ray CG, Sherris JC.

Sherris Medical Microbiology

. 5th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Medical; 2010. <

http://www.accessmedicine.com/resourceTOC.aspx?resourceID=656

>.

Sabiston DC, Townsend CM.

Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: the Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice

. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2008.

A 35-year-old Woman Who Needs a Lipoma Removed in Clinic

A 35-year-old Woman Who Needs a Lipoma Removed in Clinic

Other books

The Armchair Bride by Mo Fanning

A Taste for Blood by Erin Lark

Vegas Miracle by Crowe, Liz

The Mansion of Happiness by Jill Lepore

Monday Mornings: A Novel by Sanjay Gupta

El Ultimo Narco: Chapo by Malcolm Beith

Seductions (Alpha City Book 4) by Bryce Evans

Capitol Offense by William Bernhardt

Evolution by Kate Wrath

Current by Abby McCarthy