Resident Readiness General Surgery (36 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

3.

When you walk into any surgical ICU today, you have access to machines that can support almost all failing organ systems. The oldest, and arguably the best, of these devices is the ventilator. There are both hard and soft rules relating to when you breathe for your patient and when you can safely cut the patient loose (and the indices for starting and stopping are really the same criteria):

A. Most importantly, the patient’s mental status must be adequate to protect his/her own airway.

B. Respiratory rate below 25 to 30. Again, breathing is a high priority for all of us. Although you and I are currently expending only 3% of our energy on “breathing,” a big burn can exert 25% of energy expenditure on the “work of breathing” and leave little residual energy for “getting better.”

C. Your patient’s lungs have got to be “working.” Carbon dioxide excretion is a linear function of alveolar ventilation, so if patients can “breathe harder,” they can rid themselves of CO

2

. Oxygenation is not so simple. By the time

hemoglobin crosses halfway across a ventilated alveolus, it is already fully saturated with oxygen. So, increasing the inhaled oxygen (in a patient with a shunt) won’t help at all.

D. Strength is important, but it is hard to measure unless the patient is intubated. Negative inspiratory force (NIF) is an extubation parameter only. You and I can comfortably generate 100 mm Hg NIF. A patient who can only pull −25 mm Hg is solidly in the gray zone.

Putting It All Together

For the surgical intensivist, the following guidelines apply:

Intubation: After examining the aforementioned parameters, when

you

get frightened, intubate.

Extubation: After examining the aforementioned extubation criteria, when

you

are comfortable, extubate.

Tracheostomy: After living with your patient for 10 days, if you don’t “feel” that he can fly, trach him.

Does anyone think this is science? It is art!

TIPS TO REMEMBER

“Agitation” in the SICU/PACU represents a hypoxemic patient until proven otherwise.

The “driver” of minute ventilation in the vast majority of patients is CSF pH—not oxygen.

“Dyspnea” is a feeling—not a blood gas.

Most inhalational anesthetics inhibit healthy hypoxic pulmonary arteriolar vasoconstriction.

Increasing the inspired oxygen concentration in a patient with a shunt doesn’t help.

COMPREHENSION QUESTION

1.

You are called about an elderly patient who is in the PACU. He is extremely agitated and is trying to hit the staff. Which of the following is the correct answer(s)?

A. Sedate him with a benzodiazepine (eg, lorazepam).

B. Check his vitals.

C. Check an ABG.

D. Check an EKG.

Answer

1.

B, C, and D

. The important point is that answer A is wrong. In the acute postoperative period this patient’s agitation most likely represents cerebral hypoxia. This could be due to several factors, including inadequate cardiac output or inadequate respiration. The vital signs are quick and easy to obtain and can help guide further workup. If they reflect inadequate oxygenation or are normal, then an ABG is indicated. An EKG is indicated if you suspect inadequate cardiac output, since this could be caused by a myocardial infarction or arrhythmia.

A Patient Who Is Postoperative Day 2 With New-onset Chest Pain

A Patient Who Is Postoperative Day 2 With New-onset Chest Pain

Alden H. Harken, MD and Brian C. George, MD

You are in the middle of running the labs for all of your patients when you get a page. It says: Mr. Roberts is complaining of chest pain.—Pat MacDonald RN, phone 5-1234.

You remember that Mr. Roberts is on the exact other side of the hospital from where you are now. You pull out your cell phone and return the page as you are walking to the elevator. While you are on hold, you look at your list and see that Mr. Roberts is a vasculopath who is postoperative day 2 from a right below-the-knee amputation.

You get the nurse on the phone as you push the button for the elevator.

1.

What is your first question to the nurse?

2.

What diagnostic tests should you order over the phone?

3.

Name 6 causes of chest pain that you must not miss.

CHEST PAIN

With disconcerting frequency you are going to be called to the emergency department, the recovery room (PACU), or the floor to see a patient who claims to have new-onset “chest pain.” Frequently this will be “nothing.” Sometimes it will be “something” and, occasionally, it will be “a really big deal.”

Answers

1.

“What are the vital signs?”

This question determines your next response. Based on those vital signs you should initiate any needed supportive measures. Standard supportive measures include giving oxygen and pain control (both of which are protective if the patient is having an MI). If the patient is hypotensive, you should tell the nurse to call a code.

2.

As you are going to see the patient, you can get a couple of things going so they will be available as soon as possible. An EKG is mandatory. Unless you are confident that the cause of the chest pain can be explained by some other benign process, you should also order a CXR.

3.

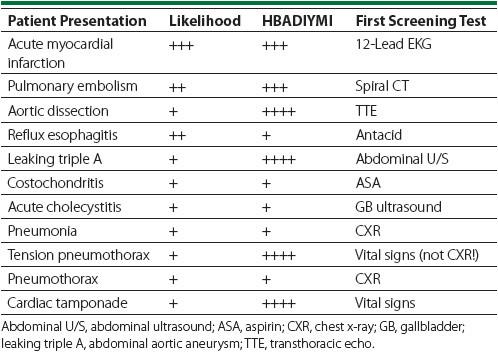

In evaluating patients with chest pain, it is useful to relate the likely epidemiological frequency of the problem to (most importantly)

How Big A Deal If You

Miss It

(HBADIYMI) (see

Table 27-1

). Note that there are 6 diagnoses with HBADIYMIs of 3+ or higher.

Table 27-1.

Causes of Chest Pain

Acute myocardial infarction

: In a 60-year-old cigar-chomping male, not only this happens, but also, in the perioperative period, the 30-day mortality increases by an order of magnitude (7% nonsurgical to 70% intraoperative in the Mayo Clinic series). Give an aspirin while obtaining a 12-lead ECG and cardiac enzymes.

Pulmonary embolism

: In a 60-year-old patient soon following a pelvic operation for cancer, this is a frequent problem. If the patient is hypotensive, call for help. If the patient is stable, obtain a spiral CT. These studies are now so sensitive that they often pick up tiny PEs that are clinically irrelevant (but this decision is above your pay grade). It is OK to give 5000 U of heparin to a patient more than 48 hours, and lytic agents more than 8 days, following thoracoabdominal surgery.