Resident Readiness General Surgery (63 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

6.

On what postoperative day should you restart her antiplatelet and anticoagulation medications?

PERIOPERATIVE ANTICOAGULATION AND ANTIPLATELET DRUGS

Perioperative management of anticoagulation and antiplatelet drugs can often be overwhelming for the junior resident since improper decision making can have serious consequences. Moreover, this area of perioperative medicine has been involved in the highest number of litigation events. These facts are only stated to emphasize that a multidisciplinary approach should be encouraged in dealing with perioperative anticoagulation. Typically, the decision should at a minimum include the patient, the surgeon, and the patient’s primary care physician or

cardiologist. That being said, there is no reason for this subject to cause intimidation as there is an algorithmic and methodical way to go about dealing with it.

The first question that should always be considered is whether or not the procedure is elective or emergent, and if elective, whether the procedure should be delayed. Regardless of whether or not anticoagulants will be held, the timing of an operation can have a significant impact on the risk of postoperative thrombotic complications. For example, patients who have experienced venous thromboembolism are at the highest risk for recurrence within the first three months. Likewise, patients who have experienced an arterial embolic event from a cardiac source have a risk of recurrence of 0.5% per day in the first month. Finally, in the case of antiplatelet agents that were started for coronary stent placement, it is recommended that these medications be continued through the perioperative period if the stent was placed less than six weeks prior for bare metal stents, or less than 12 months prior for drug-eluting stents. Stopping antiplatelet agents within these windows may otherwise lead to a devastating stent thrombosis. Given these considerations, sometimes the best option is to simply delay an elective operation.

Answers

1.

The patient underwent coronary stent placement one month ago. Because of this, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association guidelines recommend that her antiplatelet therapy not be discontinued for a minimum of six weeks in the case of a bare metal stent, and a minimum of 12 months for a drug-eluting stent. In general, patients who undergo placement of a drug-eluting stent will be started on two antiplatelet agents. (This patient was only started on Plavix because she was already taking warfarin.) Current guidelines advise continuing both agents for a minimum of 12 months. In very rare cases, it is reasonable to stop one of the agents; however, aspirin should typically be continued. The exact guidelines continue to evolve and some studies now suggest that antiplatelet agents may be stopped as early as six months following drug-eluting stent placement. Operating on this patient within the 12-month window would mean continuing her Plavix and subsequently, significantly increasing her bleeding risk. Although her hernia has become mildly symptomatic, there is no evidence of strangulation, incarceration, or previous obstruction to suggest that she meets criteria for an emergent repair. Her operation should therefore be delayed until antiplatelet therapy can be safely held in the perioperative period to avoid the risk of bleeding and catastrophic coronary stent thrombosis. Because of the complex and evolving nature of guidelines related to the use of antiplatelet agents in patients with coronary stents, consultation with a cardiologist is always recommended. This will also serve the medicolegal purpose of protecting the surgeon, should an adverse event related to the stent occur.

2.

The next question in the algorithm is to determine whether or not the patient’s anticoagulation needs to be held for the surgical procedure being considered.

A consideration of all surgical procedures is beyond the scope of this chapter; however, for the average junior surgical resident, the literature suggests that minor dermatologic excisions and many GI endoscopic procedures can be performed without holding warfarin. In the case of dermatologic excisions such as the removal of actinic keratoses, basal and squamous cell cancers, and premalignant or cancerous nevi, the literature suggests a three-fold increase in bleeding risk if the procedure is performed while the patient is on warfarin. However, most bleeds were self-limiting. It is important to note that in the case of GI procedures, the addition of a biopsy or sphincterotomy generally requires correction of coagulopathy prior to the procedure. Any other major surgical procedure is likely to require that warfarin or antiplatelet medications be temporarily held. Therefore, once the patient in the above case is ready to undergo an elective hernia repair, both her Plavix and her warfarin will need to be held.

3.

In order to determine the timing of antiplatelet therapy cessation prior to an operation, the mechanism of action of the medication must be considered. While NSAIDs

reversibly

inhibit cyclooxygenase, aspirin

irreversibly

inhibits the enzyme. As a result, the effect of aspirin does not wear off until new platelets are synthesized, a process that takes approximately 7 to 10 days. Therefore, aspirin should be held 7 to 10 days prior to an operation, assuming there is no contraindication. Thienopyridines such as Plavix work by inhibiting ADP-mediated platelet aggregation. Some are short-acting and may be discontinued 24 hours before surgery, but in the case of Plavix, which is long-acting, the medication should be held for 7 days prior.

4.

Again, determining the timing of medication cessation is based on the mechanism of action of the specific medication and the associated pharmacokinetics. Warfarin works by inhibiting vitamin K–dependent carboxylation of factors II, VII, IX, and X. Therefore, in order for the effects of the medication to wear off, new coagulation factors have to be synthesized. The literature suggests that, in general, warfarin should be held five days prior to surgery. This number comes from a series of studies demonstrating an average preoperative INR of 1.2 after warfarin was held for five days, and from the fact that five days is approximately two half-lives of factor II—enough time for the levels to become adequate for proper hemostasis.

To summarize, the steps in the algorithm so far have been to first ask if the patient’s operation should be delayed for any reason such as venous thromboembolism within the last three months, coronary stent placement in the last six weeks or 12 months depending on the type of stent, and whether there has been an episode of arterial thromboembolism in the last month. Assuming there is no contraindication to proceeding with surgery, the next step is to determine whether there is even a need to hold anticoagulation—this might be true if, for example, the patient is undergoing a procedure at low risk of significant bleeding. If anticoagulation (ie, warfarin) is going to be held, we arrive at the next point in the decision tree: should bridging therapy be used?

5.

The decision of whether or not to bridge the patient ultimately depends on the bleeding risk balanced against the risk of arterial and venous thromboembolism. The risk of thromboembolism varies based on the severity of the underlying disease, and can be classified as high, moderate, or low. The criteria used to classify the most common reasons for anticoagulation—mechanical heart valve, atrial fibrillation, and venous thrombosis—are listed below.

For patients with a mechanical heart valve:

High-risk patients include those with any type of mechanical valve in the mitral position, anyone with an older model of mechanical valve in the aortic position (ie, ball and cage valve), or anyone with a stroke or TIA related to the valve in the past six months.

Moderate-risk patients include those with bicuspid aortic valves plus one of the following: atrial fibrillation, prior stroke or TIA, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, or patients who are older than 75.

Low-risk patients are those with bileaflet aortic valves without atrial fibrillation and no other risk factors for stroke.

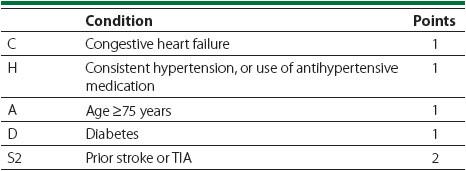

For patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), the risk is based on the CHADS2 score that is calculated in

Table 48-1

.

Table 48-1.

Calculation of CHADS2 Score

High-risk patients with AF include those with a CHADS2 score of 5 or 6, a recent stroke or TIA within the last three months, or those with rheumatic valvular heart disease.

Moderate-risk patients include those with a CHADS2 score of 3 or 4.

Low-risk patients include those with a CHADS2 score of 0 to 2.

For patients with previous venous thromboembolism:

High-risk patients are those with a recent venous thromboembolism within the last three months, or those with a severe thrombophilia.

Moderate-risk patients include those with a venous thromboembolism within the last 3 to 12 months, those with recurrent venous thromboembolism, those with active cancer, or those with a nonsevere thrombophilic condition such as factor V Leiden deficiency.

Low-risk patients include those with a single venous thromboembolism within the past year, and no other risk factors.

In most cases, patients at high risk should undergo bridging therapy with intravenous unfractionated heparin (IVUH) or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). Patients at moderate risk may or may not need bridging depending on their individual circumstances, and patients at low risk may not require bridging at all. It is important to emphasize that the patient should be included in the discussion about whether or not to bridge as many patients are more concerned about the possibility of a stroke than a bleeding event. This is a reasonable concern given that recurrent venous thromboembolism is fatal in 5% to 10% of cases and that arterial thromboembolism is fatal in 20% of cases. In cases where arterial thromboembolism is not fatal, it causes permanent disability at least 50% of the time. This is in contrast to major bleeding events that, while fatal 9% to 13% of the time, rarely cause permanent disability.

Our patient in the case above has diabetes, hypertension, CHF, and a history of a TIA a few years ago. Therefore, her CHADS2 score is 5 placing her at high risk for an event. She should therefore undergo bridging therapy at the time of hernia repair.

In general, bridging therapy should be started approximately 36 hours after the last dose of warfarin. The time at which bridging therapy should stop is based on the half-life of the medication used for bridging, generally five elimination half-lives prior to the procedure. The half-life of LMWH is approximately five hours, and if it is dosed BID, the last dose should be given 24 hours before surgery. If LMWH is dosed once daily, then the dose given 24 hours prior to surgery should be 50% of the therapeutic dose. The half-life of IVUH is approximately 45 minutes and, therefore, unfractionated heparin should generally be held four hours prior to a procedure.

6.

No clinical data support a definitive regimen for when to resume bridging, anti-platelet, or anticoagulation therapy in the postoperative period. As a result, the timing is, in practice, highly variable. The lack of clear recommendations does not diminish the importance of these decisions, as bleeding is more than a theoretical risk—for example, evidence suggests that there is a 5- to 6-fold increased rate of major bleeding in patients who receive full (ie, therapeutic) dose LMWH or IVUH in the immediate postoperative period. As a general guide, one should wait approximately 24 hours, and perhaps 48 to 72 hours if there is concern for major bleeding. These time frames are based on the physiology of hemostasis and the time required for the platelet plug to form and stabilize.

While antiplatelet medications and bridging anticoagulation therapy have a rapid onset of action, warfarin typically requires more time to deplete the vitamin K–dependent clotting factors. For this reason there are some circumstances in which the first postoperative dose can be given on the evening after surgery, or on the morning of postoperative day 1. If bridging is employed, IVUH or LMWH should be continued until the target INR is achieved.

The timing of restarting antiplatelet therapy is more variable and the decision should be a multidisciplinary one involving the patient’s cardiologist or antiplatelet medication prescriber. More broadly, any decisions with regard to the resumption of antiplatelet or anticoagulation medications should obviously involve discussion with the primary surgeon.