Resident Readiness General Surgery (15 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

Drugs/toxins, metabolic/endocrine disorders, hematologic diseases, and inflammatory/infectious processes can all present similar to generalized peritonitis but should be treated medically.

Patients with surgical causes of generalized peritonitis should be hydrated and started on empiric antibiotic coverage for anaerobes and gram-negative bacteria.

Junior residents should inform their seniors of any patient with generalized peritonitis sooner rather than later!

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.

Why isn’t “early” ischemic bowel associated with generalized peritonitis?

A. It hasn’t involved enough bowel.

B. The parietal peritoneum is not inflamed.

C. The visceral and parietal peritoneum are not inflamed.

2.

Which of the following processes can mimic generalized peritonitis?

A. Myocardial infarction

B. Pneumonia

C. Pregnancy

D. Sickle cell disease

3.

What organisms should be covered in the empiric antibiotic therapy for generalized peritonitis?

A. Anaerobes + gram-positive rods

B. Anaerobes + gram-negative enteric bacteria

C. Aerobic organisms only

D. Anaerobic organisms only

Answers

1.

B

. Generalized peritonitis indicates that the parietal peritoneum is diffusely irritated. In early ischemic bowel there is neither transmural inflammation nor perforation, and the somatic afferents of the parietal peritoneum are not yet activated. There is of course significant visceral pain even while there is no tenderness.

2.

D

. An acute sickle cell crisis can present with a diffuse abdominal pain that may be difficult to distinguish from a surgical disorder causing generalized peritonitis.

3.

B

. Empiric antibiotic coverage for generalized peritonitis should cover the major GI pathogens, including primarily anaerobes and gram-negative enteric bacteria.

A Patient in the ER With a Blood Pressure of 60/–and a Heart Rate of 140

A Patient in the ER With a Blood Pressure of 60/–and a Heart Rate of 140

Alden H. Harken, MD and Brian C. George, MD

A new patient arrives by private vehicle to the ER. The nurse runs over from triage and says to you: “Doctor, this patient doesn’t look so good.”

You bring him back to the trauma bay and check his vital signs: his blood pressure is 60/—and his heart rate is 140.

1.

Is this patient in shock?

2.

What is the first thing you would do to treat his hypotension?

SHOCK

Answers

1.

Given the information in the case, we can’t actually tell. Remember, “shock” is not just “looking bad” and is not just a low blood pressure. And shock is not just decreased peripheral perfusion. And shock is not just reduced systemic oxygen delivery. Ultimately, shock is decreased end-organ tissue respiration. Stated differently, “shock” is suboptimal oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide excretion at the cellular level.

The most practical method of diagnosing shock is to look at end-organ function. The organs most sensitive to hypoperfusion are the brain and the kidneys. A confused or anxious patient should be a source of concern, just as oliguria should trigger you to investigate further. Perfusion of the skin and extremities can also be sensitive indicators of shock, as the body preferentially shunts blood to the core when cardiac output is compromised. This is why surgeons will often feel the big toe as a quick and dirty measure of cardiac output. Other organ systems can of course also be hypoperfused, but evidence of, for example, cardiac or hepatic dysfunction is usually a late sign.

Another method of diagnosing shock is to look for systemic signs of decreased end-organ tissue respiration. This is most easily done by measuring the pH of the blood. While arterial blood gases are traditionally used, venous blood gases can also be of huge practical clinical value when a patient is really sick. Venous gases reflect arterial acid/base status with useful precision. Just add 0.05 to the venous pH and you will get the arterial pH. Subtract 5 from the arterial P

CO

2

and you get arterial P

CO

2

. So you don’t need to repeatedly stick the artery (see

Table 12-1

).

Table 12-1.

How to Interpret Venous Blood Gases

A little bit like sorting your socks, some surgeons are more comfortable “classifying” shock—all the while acknowledging that it is the cardiovascular response to a stressor (blood loss/myocardial ischemia) that dictates the danger. Class I (fully compensated) shock is how a young healthy patient presents following a 2-U (750 mL) bleed. This young person can vasoconstrict, diverting blood flow away from his extremities in a manner that preserves completely normal coronary and carotid flow. The problem, of course, is that the same 2-U bleed in a Supreme Court justice may prove lethal.

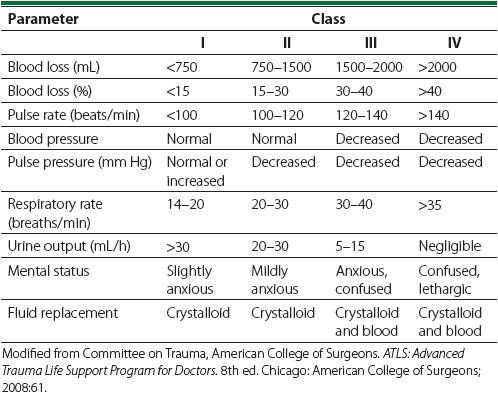

On the other end of the clinical spectrum, class IV shock represents a near-death state that is seen with severe blood loss (eg, 6 U, or 2000 mL). If the patient is still alive, there will almost certainly be severe organ dysfunction, including coma and/or stroke, renal failure, and myocardial ischemia (see

Table 12-2

).

Table 12-2.

Classification of Shock

2.

“Shock” may be treated in a logically sequential fashion that is the same for all patients. So, when a chubby, cigar-chomping, sixtyish personal injury lawyer presents hypotensive with a big GI bleed, or with crushing chest pain, or with a sigmoid perforation, you should activate the following steps in order:

A.

Optimize volume status

: Give the patient volume until an increase in the right-sided central venous pressure (CVP) and/or left-sided pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) confers no additional benefit to either blood pressure or cardiac output. This is strictly Starling law. It doesn’t make any difference how good the engine is, if there is no gas in the tank. You want your patient’s ventricles working at the top of this Starling curve (

Figure 12-1

). In the absence of a Swan catheter it can sometimes be difficult to precisely measure the cardiac output—in those cases, you can also target a CVP of 8 to 12.

Other books

The Castle by Franz Kafka, Willa Muir, Edwin Muir

When the Lion Feeds by Wilbur Smith, Tim Pigott-Smith

Agnes Owens by Agnes Owens

Forever An Ex by Victoria Christopher Murray

The Outcast Ones by Maya Shepherd

By Book or by Crook by Eva Gates

Mountain Devil by Sue Lyndon

How I Lost You by Janet Gurtler

The Double Death of Quincas Water-Bray by Jorge Amado

Home Ice by Katie Kenyhercz