Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (46 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

The army switches to flatboats, but just as these are launched the temperature falls and the boats are frozen fast along the Sandusky, Au Glaize, and St. Mary’s rivers. By early December, Harrison despairs of reaching the rapids at all and makes plans to shelter his force in huts on the Au Glaize. He suggests that Shelby prepare the

public for a postponement in the campaign by disbanding all the volunteer troops except those needed for guard and escort duty. But Washington will have none of it. The Union has suffered two mortifying failures at Detroit and Queenston; it will not accept a third.

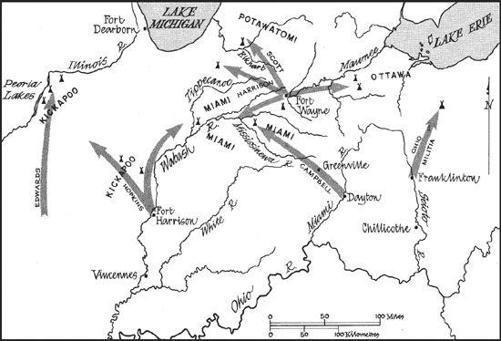

American Search and Destroy Missions against the Tribes, Autumn, 1812

The setbacks continue. Hopkins’s failure has left Harrison’s left flank open to Indian attack. He decides to forestall further Indian raids on Winchester’s line of communications by striking at the Miami villages along the Mississinewa, a tributary of the Wabash in Indiana Territory. On November 25, Lieutenant-Colonel John Campbell and six hundred cavalry and infantry set out to do the job. The result is disastrous.

In spite of Campbell’s attempts at secrecy, the Miami are forewarned. They leave their villages, wait until the troops are exhausted, then launch a night attack, destroying a hundred horses, killing eight men, wounding forty-eight. A false report is spread that the dreaded Tecumseh is on the way at the head of a large force. Campbell’s dejected band beats a hasty retreat.

It is bitterly cold; provisions are almost gone; the wounded are dying from gangrene, the rest suffer from frostbite. A relief party

finally brings them into Greenville, where it is found that three hundred men—half of Campbell’s force—are disabled. One mounted regiment is so ravaged it is disbanded. Harrison has lost the core of his cavalry without any corresponding loss among the Indians. The General decides to put a bold front on the episode: he announces that the expedition has been a complete success. He has learned something from the experience of Tippecanoe.

By December 10, Harrison has managed to get his cannon to Upper Sandusky, but at appalling cost. He has one thousand horses, hauling and pulling; most are so exhausted they must be destroyed, at a cost of half a million dollars. Wagons are often abandoned, their contents lost or destroyed. The teamsters, scraped up from frontier settlements, are utterly irresponsible. “I did not make sufficient allowance for the imbecility and inexperience of public agents and the villainy of the contractors,” Harrison writes ruefully to the acting secretary of war, James Monroe, who has replaced the discredited Dr. Eustis.

Winchester’s left wing is still pinned down near the junction of the Maumee and the Au Glaize, waiting for supplies. It is impossible to get them through the Black Swamp that lies between the Sandusky and the Maumee. William Atherton, a diminutive twenty-one-year-old soldier in Winchester’s army who is keeping an account of his adventures, writes that he now sees “nothing but hunger and cold and nakedness staring us in the face.” The troops have been out of flour for a fortnight and are existing on bad beef, pork, and hickory nuts. Sickness and death have reduced Winchester’s effective force to eleven hundred. Daily funerals cast a pall over the camps, ravaged by the effects of bad sanitation and drainage (Winchester is forced to move the site five times) and the growing realization that there is no chance of invading Canada this year.

On Christmas Eve, another soldier, Elias Darnell, confides to his journal that “obstacles had emerged in the path to victory, which must have appeared insurmountable to every person endowed with common sense. The distance to Canada, the unpreparedness of the army, the scarcity of provisions, and the badness of the weather,

show that Malden cannot be taken in the remaining part of our time.… Our sufferings at this place have been greater than if we had been in a severe battle. More than one hundred lives … lost owing to our bad accommodations! The sufferings of about three hundred sick at a time, who are exposed to the cold ground, and deprived of every nourishment, are sufficient proofs of our wretched condition! The camp has become a loathsome place.…”

On Christmas Day, Winchester receives an order from Harrison. He is to move to the Rapids of the Maumee as soon as he receives two days’ rations. There he will be joined by the right wing of the army. Two days later, a supply of salt, flour, and clothing arrives. Winchester, eager to be off, sets about building sleds, since his boats are useless. On December 29, he is ready. The troops are exuberant—anything to be rid of this pestilential camp! But Darnell realizes what they are facing:

“We are now about commencing one of the most serious marches ever performed by the Americans. Destitute, in a measure, of clothes, shoes and provisions, the most essential articles necessary for the existence and preservation of the human species in this world and more particularly in this cold climate. Three sleds are prepared for each company, each to be pulled by a packhorse, which has been without food for two weeks except brush, and will not be better fed while in our service.…”

The following day, the troops set off for the Maumee rapids. Few armies have presented such a ragtag appearance. In spite of the midwinter weather, scarcely one possesses a greatcoat or cloak. Only a lucky few have any woollen garments. They remain dressed in the clothes they wore when they left Kentucky, their cotton shirts torn, patched, and ragged, hanging to their knees, their trousers also of cotton. Their matted hair falls uncombed over their cheeks. Their slouch hats have long since been worn bare. Those who own blankets wrap them about their bodies as protection from the blizzards, holding them in place by broad belts of leather into which are thrust axes and knives. The officers are scarcely distinguishable from the men. They carry swords or rifles instead of long guns and a

dagger—often an expensive one, hand-carved—in place of a knife.

Now these men must become beasts of burden, for the horses are not fit to pull the weight. Harnessed five to a sleigh, they haul their equipment through snow and water for the next eleven days. The sleighs, it develops, are badly made—too light to carry the loads, not large enough to cross the half-frozen streams. Provisions and men are soon soaked through. But if the days are bad, the nights are a horror. Knee-deep snow must be cleared away before a camp can be made. Fire must be struck from flint on steel. The wet wood, often enough, refuses to burn. So cold that they cannot always prepare a bed for themselves, the Kentuckians topple down on piles of brush before the smoky fires and sleep in their steaming garments.

Then, on the third day, a message arrives from Harrison:

turn back!

The General has picked up another rumour that the redoubtable Tecumseh and several hundred Indians are in the area. He advises—does not order—Winchester not to proceed. With the Indians at his rear and no certainty of provisions at the rapids, any further movement toward Canada this winter would be foolhardy.

But James Winchester is in no mood to retreat. He is a man who has suddenly been released from three months of dreadful frustration—frustration over inactivity and boredom, frustration over insubordination, frustration over sickness and starvation, and, perhaps most significant, frustration over his own changing role as the leader of his men. Now at least he is on the move; it must seem to him some sort of progress; it is action of a sort, and at the end—who knows? More action, perhaps, even glory … vindication. He has no stomach to turn in his tracks and retreat to that “loathsome place,” nor do his men. And so he moves on to tragedy.

AT FORT AMHERSTBURG

, Lieutenant-Colonel Procter has concluded that the Americans have gone into winter quarters. His Indian spies have observed no movement around Winchester’s camp for several weeks, and he is convinced that Harrison has

decided to hold off any attempt to recapture Detroit until spring. It is just as well, for he has only a skeleton force of soldiers and a handful of Indians.

The Indians concern Procter. He cannot control them, cannot depend on them, does not like them. One moment they are hot for battle, the next they have vanished into the forest. Nor can he be sure where their loyalties lie. Matthew Elliott’s eldest son, Alexander, has been killed and scalped by one group of Indians who pretended to be defecting to the British but who were actually acting as scouts for Winchester. Brock called them “a fickle race”; Procter would certainly agree with that. Neither has been able to understand that the Indians’ loyalty is not to the British or to the Americans but to their own kind. They will support the British only as long as they believe it suits their own purpose. But the British, too, can be fickle; no tribesman, be he Potawatomi, Wyandot, Shawnee, or Miami, can ever quite trust the British after the betrayal at Fallen Timbers in 1794.

Nor do the British trust them—certainly not when it comes to observing the so-called rules of warfare, which are, of course, white European rules. Tecumseh is the only chief who can restrain his followers from killing and torturing prisoners and ravaging women and children. Angered by Prevost’s armistice and ailing from a wound received at Brownstown, Tecumseh has headed south to try to draw the Creeks and Choctaws to his confederacy. His brother, the Prophet, has returned to the Wabash.

Procter needs to keep the Indians active, hence his attempt to capture Fort Wayne with a combined force of natives and regulars. The attempt failed, though it helped to slow Harrison’s advance. Now he is under orders from Prevost to refrain from all such offensive warfare. His only task is defence against the invader.

He must tread a line delicately, for the Indians’ loyalty depends on a show of British resolution. As Brock once said, “it is of primary importance that the confidence and goodwill of the Indians should be preserved and that whatsoever can tend to produce a contrary effect should be carefully avoided.” That is the rub. The only way

the confidence and goodwill of the Indians can be preserved is to attack the Americans, kill as many as possible, and let the braves have their way with the rest. Procter is not unmindful of how the news of the victory at Queenston has raised native morale—or of how the armistice has lowered it.

Prevost, as usual, believes that the British have overextended themselves on the Detroit frontier. Only Brock’s sturdy opposition prevented the Governor General from ordering the evacuation of all captured American territory to allow the release of troops to the Niagara frontier. But Brock understood that such a show of weakness would cause the Indians to consider making terms with the enemy.

Brock’s strategy, which Procter has inherited, has been to let the Americans keep the tribes in a state of ferment. The policy has succeeded. Harrison’s attempt to subdue the Indians on the northwestern frontier has delayed his advance until midwinter and caused widespread indignation among the natives. Some six thousand have been displaced, nineteen villages ravaged, seven hundred lodges burned, thousands of bushels of corn destroyed. Savagery is not the exclusive trait of the red man. The Kentuckians take scalps whenever they can, nor are women and children safe from the army. Governor Meigs had no sooner called out the Ohio militia in the early fall than they launched an unprovoked attack on an Indian village near Mansfield, burning all the houses and shooting several of the inhabitants.

The worst attacks have been against the villages on the Peoria lakes, destroyed without opposition by a force of rangers and volunteers under Governor Ninian Edwards of Illinois Territory. One specific foray will not soon be forgotten: a mounted party under a captain named Judy came upon an Indian couple on the open prairie. When the man tried to surrender, Judy shot him through the body. Chanting his death song, the Indian killed one of Judy’s men and was in turn riddled with bullets. A little later the same group captured and killed a starving Indian child.

In their rage and avarice, Edwards’s followers scalp and mutilate the bodies of the fallen and ransack Indian graves for plunder. Small wonder that the Potawatomi chief Black Bird, in a later discussion

with Claus, the Canadian Indian superintendent, cries out in fury, “The way they treat our killed and the remains of those that are in their graves to the west make our people mad when they meet the Big Knives. Whenever they get any of our people into their hands they cut them like meat into small pieces.”