Uncle John's Ahh-Inspiring Bathroom Reader (50 page)

Read Uncle John's Ahh-Inspiring Bathroom Reader Online

Authors: Bathroom Readers' Institute

Lallement arrived in Ansonia, Connecticut, in 1865. With little money to his name, he got a job in a carriage shop and in his spare time built what historians consider to be the first American bicycle.

He arranged to exhibit his new machine by staging a four-mile ride from Ansonia to the neighboring town of Derby and back. The first leg was mostly uphill, which was difficult. The ride back, however, was disastrous. At first, spectators were amazed to see Lallement speeding down the hill, but their excitement turned to horror when they realized he had no control over his machineâthe veloce hit a rut, stopped, and the Frenchman went flying over the handlebars.

Undeterred, Lallement earned an American patent in 1866, but the rough New England roads and even rougher winters made the veloce a tough sell. So Lallement finally gave up and returned to France. When he got to Paris, what he saw amazed him: Parisians were riding around on veloces!

Stall tactic: John McEnroe once tied his shoelaces seven times during a match at Wimbledon.

Lallement's former employer, carriage maker Pierre Michaux, had copied Lallement's design and renamed it the

velocipede

(rough translation: “speed through feet”). With the help of his son, Ernest, Michaux built the first velocipede in 1863. In 1867 they displayed it at the Paris World's Fair and it attracted so much attention that Michaux decided to dedicate all of his resources to producing them. Soon velocipedesâ“boneshakers” as they were nicknamed because of their lack of suspension and adequate brakesâbecame popular all over Europe.

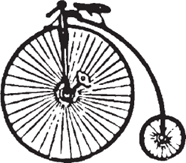

English mechanics came up with the next big innovation in bicyclesâthey increased the size of the front wheel. Because the pedals were attached directly to the axle, the larger the wheel, the farther a person could go with one rotation of the pedals. In some instances, the front wheel was four or five feet in diameter. At the same time, the rear wheel shrunk in size to give the bicycle better balance. The new machine became known as the “penny-farthing” because of the drastic disparity between the size of the front and rear wheels (it resembled two British coins, the penny and the farthing, placed next to each other). Now the rider had to carefully climb up the bike to get it goingânot an easy task. But thankfully, penny-farthings were the first bikes with brakes.

The penny-farthing was introduced to America at the 1876 Philadelphia World's Fair, and people loved it. To cash in on the public interest, a Boston architect named Frank W. Weston founded a company to import penny-farthings from England. They were a big hit, but because they cost well over $100 each ($1,670 in today's dollars), they were only available to the rich. Aristocrats formed exclusive “riding clubs” in upscale neighborhoods with indoor tracks and private riding instructors. Middle-class people wanted to join in on the fun, but few could afford the expensive import.

Colonel Albert Pope, however, was about to change all that.

For Part III of the story, turn to page 366.

In some parts of India, girls get names with an odd number of syllables; boys get even.

Some stupid criminals actually go someplace to commit their crimes and get caught. These three lazy guys figured they could just phone it in. They were right.

O SUCH THING AS A FREE RIDE

“In August of 1996, 19-year-old Donterio Beasley got stranded in Little Rock, Arkansas, and called police to request a ride downtown. When informed that it was against police policy, he hung up, waited a few minutes, and called back again. This time he reported a suspicious looking person loitering near a phone boothâ¦and then he gave a complete description of himself. He thought he'd get a free ride downtown to the station, where he'd be questioned and released. Instead he got a free ride downtown and was charged with calling in a false alarm.”

âDallas Morning News

“Ron Vanname was 21 years old in 1992 when he decided to make some prank obscene phone calls from a phone booth in Port Charles, Florida. He decided to make the calls to the 911 operator, and phoned nine times in sixteen minutes with new vulgarities each time. He was unaware that the 911 phone system automatically showed the address of every incoming phone call. Squad cars surrounded him before he'd even hung up the phone. He spent a week in jail.”

âThe Wolf Files

“Thirty-nine-year-old Ronnie Wade Cater of Hampton, Virginia, was arrested in 1997 after phoning in a bomb threat. Cater was at a bar, drunk, and wanted to drive home without being nabbed for DUI. So he phoned in his bomb threat saying there was a bomb at another local bar, hoping to divert police attention. The call was traced and he was arrested.”

âNews of the Weird

National religion of Haiti (unofficially): voodoo.

From 1896 to 1926, Harry Houdini was the world's most famous escape artist. He could get out of anything. There was no lock or latch that could hold him. How'd he do it? We'll never tell. Okay, you talked us into it.

T

HE TRICK:

Escaping from a locked container

THE SECRET:

Hidden tools

EXPLANATION #1:

Houdini often hid tools by swallowing them. He learned the trick while working for a circus, when an acrobat showed him how to swallow objects, then bring them up again by working the throat muscles. Houdini practiced with a potato tied to a stringâ¦so he could be pull it back up if needed.

EXPLANATION #2:

Houdini would ask several men from the audience come up onstage, first to search him to for hidden tools, and second, to examine whatever he was about to be locked up in: a safe or a coffin or a packing crate. He would then solemnly shake hands with each man. But the last man was a shillâsomeone who had been planted in the audience. And during the handshake, a pick or a key would be passed from hand to hand.

EXPLANATION #3:

Houdini sometimes hid a slim lockpickâlike a thin piece of wireâin the thick skin of the sole of his foot.

THE TRICK:

One of his greatestâescaping from a water-filled milk canâ¦without disturbing the six padlocks that secured the lid

THE SECRET:

A fake can

EXPLANATION:

Houdini folded himself into the cylinder (or body) of an old-fashioned milk can. But the neck of the can wasn't really attached to the body. It appeared to be held together by rivets, but the rivets were fake. The two sections actually came apart. Houdini could easily break the neck from the cylinder, step out of the milk can, and then reattached it. And because the can was placed inside a box, the audience never knew how it was done.

THE TRICK:

Escaping from handcuffs

THE SECRET:

Sleight of hand

EXPLANATION:

If he couldn't pick the lock, Houdini had

another trick: he'd insist the handcuffs be locked a little higher on his forearm, then simply slip them over his wrists.

Sad irony: In spring 2001, the U.S. lost seven men searching for MIAs in Vietnam.

THE TRICK:

Mind reading

THE SECRET:

Secret stage code (and a clever assistant)

EXPLANATION:

Houdini's wife, Bess, often participated in the show. For mind-reading tricks, they worked out a secret code where one could tip off the other using words that stood for numbers: pray = 1, answer = 2, say = 3, now = 4, tell = 5, please = 6, speak = 7, quickly = 8, look = 9, and be quick = 0.

If Houdini was divining the number from a dollar bill, Bess would say, “Tell me, look into your heart. Say, can you answer me, pray? Quickly, quickly! Now! Speak to us! Speak quickly!” Then Houdini the “mind reader” would correctly reply: 59321884778.

THE TRICK:

Escaping from a straitjacket

THE SECRET:

There was no trickâhe did it in plain sight using a combination of technical skill and brute strength

EXPLANATION:

From his 1910 book

Handcuff Escapes

:

The first step is to place the elbow, which has the continuous hand under the opposite elbow, on some solid foundation and by sheer strength exert sufficient force at this elbow so as to force it gradually up towards the head, and by further persistent straining you can eventually force the head under the lower arm, which results in bringing both of the encased arms in front of the body.

Once having freed your arms to such an extent as to get them in front of your body, you can now undo the buckles of the straps of the cuffs with your teeth, after which you open the buckles at the back with your hands, which are still encased in the canvas sleeves, and then you remove the straitjacket from your body.

ONE LAST SECRET:

Often Houdini would escape quickly from his entrapment, then sit quietly out of sight of the audience, calmly playing cards or reading the paper while waiting for the tension to grow: “Is he dead yet?” “He's never going to get out alive!” Then, when the audience's murmurings and accompanying music had grown to a fever pitch, he would drench himself in water to make himself look sweaty before stepping triumphantly out in front of the curtain to humbly accept the raucous cheers.

Three words pulled from Microsoft Word's thesaurus in 2000: idiot, fool, and nitwit.

There have been many head-hunting cultures in the worldâeven the French had the guillotineâbut only one made shrunken heads. Here's the story.

HE JIVARO

The Jivaro (pronounced “hee-var-o”) tribes live deep in the jungles of Ecuador and Peru. They don't do it anymore as far as anyone knows but as recently as 100 years ago they were ardent head shrinkers. The Jivaro tribes were constantly at war with other neighboring tribes (and with each other), and they collected the heads of their fallen enemies as war trophies. The head, once shrunk, was called

tsantsa

(pronounced “san-sah”). For the Jivaro the creation of tsantsa insured good luck and prevented the soul of the fallen enemy from seeking revenge.

As Western explorers came in increasing contact with the Jivaro tribes in the late 19th century, shrunken heads became a popular souvenir. Traders would barter guns, ammo, and other useful items for shrunken heads; this “arms-for-heads” trade caused the killing to climb rapidly, prompting the Peruvian and Ecuadorian governments to outlaw head shrinking in the early 1900s. If you buy a head today, it's guaranteed a fake.

Here's the Jivaro recipe for a genuine shrunken head (Kids, don't try this at home): Peel skin and hair from skull; discard skull. Sew eye and mouth openings closed (trapping the soul inside, so that it won't haunt you). Turn inside out and scrape fat away using sharp knife. Add jungle herbs to a pot of water and bring to a boil; add head and simmer for one to two hours. Remove from water. Fill with hot stones, rolling constantly to prevent scorching. Repeat with successively smaller pebbles as the head shrinks. Mold facial features between each step. Hang over fire to dry. Polish with ashes. Moisturize with berries (prevents cracking). Sew neck hole closed. Trim hair to taste.

Second grossest fact in this entire book: You inhale about 700,000 of your own skin flakes daily.

Can a dog be a hero? These people sure think so.

G

OOD DOG:

Blue, a two-year-old Australian Blue Heeler

WHAT HE DID:

One evening in 2001, Ruth Gay of Fort Myers, Florida, was out walking her dog when she accidentally slipped on some wet grass and fell. The 84-year-old woman couldn't get up, and no one heard her cries for helpâexcept a 12-foot alligator that crawled out of a nearby canal. Gay probably would have been gator food if Blue hadn't been there to protect her. The 35-pound dog fought with the gator, snarling and snapping until the reptile finally turned tail. Then Blue ran home barking, alerting Gay's family that she was in trouble. Gay was saved. And Blue? He was treated for 30 puncture wounds. “It's amazing what an animal will do in a time of need,” said the vet. “He's a pretty brave dog.”