Umami (19 page)

Authors: Laia Jufresa

Tags: #Fiction;Exciting;Young writer;Mexico;Mexico City;Agatha Christie;Mystery;Summer;Past;Inventive;Funny;Tender;Love;English PEN

âNot true! I also always thought your drawings were good.'

âBy which you mean bad.'

âIt doesn't work both ways, smarty pants.'

*

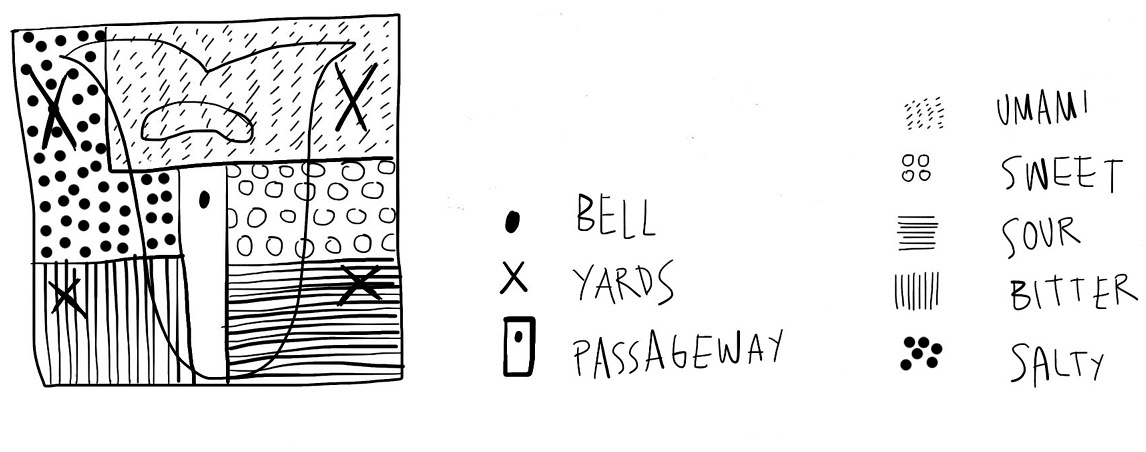

I feel it is my duty to point out, in case I die and someone finds this, that Harvard has publicly repudiated the little map of the tongue Nakahara sent me. Now, if you think about it, anyone with two brain cells and a drop of lemon on the tip of the tongue (supposedly the area that only distinguishes sweetness) could have exposed it sooner, but this didn't occur to those of us who took the map as a given (basically because it came from Harvard; we smarty pants are suckers for the smartest smarty pants). Anyway, it turned out to be a load of baloney. But it was a good map; at least, it served us well as a foundation for our plans for the mews, with an added dose of artistic license.

*

The houses in Belldrop Mews are arranged as follows:

And they're occupied as follows:

Bitter House: Marina. A young painter who doesn't eat or indeed paint much, but invents colors. For example: fusciaranth is the color of amaranth; she did that one for me. Cloggray the color of dirty water, and a pointed reminder that the gutters in the entry hall don't drain properly. Rainbowrket, that's my personal favorite: it's the multicolored light you find under the street-market awnings.

Sour House: Pina and her dad, Beto. Her mom, Chela, walked out in 2000, and left behind a letter which Beto hid and Pina spends her life trying to find. Agatha Christie told me as much.

Salty House: Linda Walker and VÃctor Pérez. Musicians in the National Symphony Orchestra and owners of the school thanks to which my life is set to an interminable, unbearable fluty tune. Their kids: Ana, AKA Agatha Christie, Theo and Olmo. And Luz, in loving memory.

Sweet House: The Pérez-Walker Academy of Music. The little sign next to the bell reads âPW'. That's all, because I don't have planning permission for my tenants to go around setting up schools. But in any case I turn a blind eye, because there are worse things than trying to spread a little bit of sol-fa in the world. And because otherwise they wouldn't make rent.

Umami House: Alfonso Semitiel, AKA me, and The Girls. The Girls are two reborn dolls who belonged to their exquisitely beautiful mother, Noelia Vargas Vargas, God rest her soul, and who I now dress and groom on an almost daily basis. One of them breathes.

*

The other day, out of nowhere in the Mustard Mug, Linda told me why she isn't playing the cello at the moment. She says she can't trust her arms. She says that sometimes she's in full flow and her arms just turn to jello.

âDid you carry her?' I asked.

She said she did, and then I understood. Or at least I think I did. Because sometimes, in the middle of the night, my arms wake me up too. Mine don't turn to jello. They go stiff; stiff at the memory of Noelia when I carried her dead. I'd carried her countless times before, especially during the last months, but she'd never weighed so much. And it wasn't just my sorrow, I'm sure of it. She really, physically weighed much more.

âWhy?' Linda asked me.

âWhy do the dead weigh more than the living?'

âUh-huh.'

âI guess it has to do with the lack of muscular tension,' I told her. âWhen you carry someone living, no matter how weak they are, they still carry themselves a little as well.'

âMaybe that's what dying is, don't you think?'

âWeighing more?'

âThe moment you stop carrying your own weight.'

*

What I like about writing is seeing the letters fill up the screen. It's something so seemingly simple, so perfectly alchemic: black on white. To plant worlds and tend them as they grow. If you're missing a comma, you add it, and now there's nothing missing. Everything this text needs is here.

And white on black, too. The pauses, the spaces, or as my friend Juan the philosopher would say: the ineffable. Everything missing from this text, its absences and silences, is here too.

I don't know if it's my age, or the sabbatical or what, but writing this I've started to realize just how fragile the system of referencing â to which I always adhered â is. Now, the academic etiquette that regulated my writing for years seems as much of a mask as those fake star-spangled nails young ladies these days wear. Bibliographical citations were invented as masks for men incapable of holding a conversation, let alone keeping eye-contact with their interlocutor. Men as dull as dishwater and deep down as insecure as the next person, but with a thin layer of intellectual pretension coating them. Timid men with delusions of grandeur. In other words, men just like me.

*

Noelia was competitive as hell. The idea of missing a convention or conference or any opportunity to come first in something horrified her. Whenever she received a prize or award she turned into a visionary, declaring that to be the first woman to achieve âx' opened the doors to the next generation. She knew that women were on the back foot, and never missed a chance to say as much in public, but saw this more as a challenge than a handicap. It was her, by the way, who used the word handicap in questions of gender. I once heard her tell a female junior doctor who called her up crying because a doctor had put his hands on her leg, that women in medicine certainly could get to the top in Mexico, but that the trick was to keep Paralympic runners in mind.

âDo you know how professional handicapped athletes get ahead?' I heard her ask, still in her inspirational voice.

âNo,' the junior must have answered.

âWith twice the effort and half the visibility,' Doctor Vargas explained.

*

It was during our stay in Morelia after the earthquake that Noelia began to regret not having had children. Perhaps it was a byproduct of the survivor's aftershock that ran through us all. Or maybe too much exposure to the family: her brother's heart attack, her quitting smoking, and the overdose of Sundays spent with cute nieces and nephews. She couldn't sleep. She would switch on the light at three in the morning and ask, deadly serious, âAren't we missing out on something?'

I would tell her that, yes, one always, irredeemably misses out on something, and that if we'd had children we'd also be missing out on something: something else. But she only ever heard me up to âyes'.

And that's how all of a sudden the decade we'd invested in defending our decision to not try for children threatened to repeat itself. Now we'd have a child and spend the next decade defending our decision to be mature parents. I was already well into my forties.

âYour wish is my command,' I told her.

And we did try, hard, but not with doctors and needles and little cups. We decided â or rather, Noelia did, in a typical snub against her own profession (ah, those people who criticize their own profession, eh?!) â that she didn't want anything to do with assisted conception. If we were going to have a child, it would be Fate who gave it to us. So, quite simply, she stopped taking her pill, and we began going at it like rabbits in a race against the menopause.

The Year of Reproduction â which was how we later came to refer to the period in which we returned to Mexico City, and which was really more like three years â coincided with the construction of the mews. We were investing so that our imaginary future ward would never want for anything. They were exhausting, superstitious and anxious times, but they never got the better of us. The truth is that we both showed ourselves to be skeptics, as much with regard to the builders as the pregnancy. And this brought us closer than ever. We suspected everything and everyone: in particular the pair of doctors we consulted, but also the construction foreman.

Saturdays went like this: we'd pay the builders their weekly wage, wait for them to leave, then make love. Apart from Saturdays and the odd siesta, we had an ovulation calendar stuck to the bathroom wall. I never really understood it, but in practical terms it worked like this: Noelia said, âNow!', and her wish was my command.

We kept clay figures at home. Imitation pre-Hispanic pieces. The kinds of knickknacks educated Mexicans buy. Apart from this educated Mexican: I got them free. Every year the institute gives its researchers a bonus coupon packet to be spent in its own stores. I never cared much for their folkloric CDs or gimmicky T-shirts, but during the Year of Reproduction, the coupons found their use: we stocked up on figurines. In fact, we took collecting pretty seriously. On a chest in the living room we arranged a selection of little fertility goddesses from different cultures. A couple of them were made from amaranth, which I was already investigating by then. Our friends even donated their mythical figures to our cause (although both Noelia and I suspected that they blew out the candles they lit for us the moment we left their houses).

One day during all this, I arrived home to find all the little statues with their heads covered with strips of cloth. When I asked Noelia what it was all about, she answered, â

a

)

How have you not noticed they've been like that for three days?, and

b

)

it's a plan I came up with, to wake them up with a bang.'

âHow do you figure that?' I asked.

âI cover their heads with a cloth, right? Then I leave them like that a few days, and around midday on Sunday, when the sun's at its brightest, I whip off the cloth and pow!'

âPow?'

âThey wake up with a bang.'

âAnd why do we want them to wake up with a bang?'

âSo they get a move on, Alfonso. So they grant us our little miracle.'

Our little miracle, of course, was the child we never had. The child we never asked for. Or rather the child we asked for, but without sufficient faith to make the gods get a move on. It didn't work. In 1991, Chela and Linda, our tenants with whom Noelia had been spending all her free time (supposedly to get some pregnancy training in), each gave birth to a baby girl. They were ten years younger than her, and by the end of the first month helping them in their new lives as mothers, Noelia decided that the whole thing was way too much at our age and decided to have her tubes tied, just in case Fate came to bite us in the ass.

Of course, it wasn't as easy as all that. We cried the tears we had to cry. The statuettes remained covered up. I was fifty. She had just turned forty-two. We decided we'd be grandparents to the little neighbors, if they'd have us, and we let go.

*

When something was a bit insipid, a bit lacking in meatiness or flavor, Noelia and I declared it âUmami No'. It sounded Japanese.

*

Feeding is another area of arrested development if you suffer from the condition of offspringhood. That's how Noelia justified her weight-gains and -losses, which began when she quit smoking.

âI don't have anyone other than myself to feed.'

âWhat am I, chopped liver?'

âYou're not growing, Alfonso. And you don't count:

a

) because you're skinny, and

b

) because it's you that feeds me.'

There was one period when I was less skinny: during that fateful year in Morelia I put on six kilos (me, who's always been a beanpole), I guess because the army of aunts would feed us at the slightest encouragement. Noelia put on fourteen kilos, and that on a diet. But in Morelia a light dessert is when they substitute sugar for condensed milk.

I think I'm putting on weight now, actually. It must be all the take-outs and tequila. Maybe I should head to the supermarket, resume old habits, make myself that soup. I used to make chicken stock every Sunday and use it to make all kinds of soups during the week, plus whatever you could whip up with the shredded chicken: sandwiches, tacos, salads. Sometimes I fantasize about investing in a battery-operated mechanism that makes The Girls eat. And since I know that no such thing exists, the rest of the time I fantasize about inventing it. Why did I become an anthropologist when I could have been an engineer, an inventor, a carpenter?

Yesterday the postman delivered an invitation from the institute to a seminar so rhetorically and pompously titled I wanted to scream. The academy is the place where the middle classes puff themselves up with their Sunday-best words and endorse the myth that knowledge is power. Load of boloney! Knowledge debilitates. Knowledge inflates the ego and starves ingenuity. To know is to use the body less and less; to live a sedentary existence. Knowledge makes you fat! Thank God I'm not advising any doctoral students at the moment, because that'd be my aphorism of choice to rip apart their empty theories about the latest trendy sacred pseudo-cereal (no doubt quinoa, which, by the way, was never

eaten in Mexico). The new kids on the block can argue with me till they're blue in the face. Go and scrape the potsherd, for Christ's sakes! Use your brain and your microscope and don't go making up crap when the truth is ten times more interesting than the drivel your tiny minds come up with!