Umami (18 page)

Authors: Laia Jufresa

Tags: #Fiction;Exciting;Young writer;Mexico;Mexico City;Agatha Christie;Mystery;Summer;Past;Inventive;Funny;Tender;Love;English PEN

âBausch? Contempo. Contemporary dance, you know what that is?'

âMore or less. You're a dancer too, right?'

âNot anymore.'

âWhat, one day you just said enough is enough?'

âNo. I couldn't find any contempo in Mazunte.'

2002

Back in 1982, while I recovered from the bike accident, Noelia took up the habit of calling me as soon as she got to work. Since we had nothing to say to each other, having only just eaten breakfast together, she would give me a report of the traffic she'd encountered on the way from our house to the hospital, putting on a voice that she thought made her sound like a sports commentator, but in fact only made her seem like a tattletale.

âHe overtook me on the right!' she'd say. Or, âI saw a man hit by a car right outside a church. There are no morals anymore!'

When, almost twenty years later, she began chemo, I took it upon myself to give her a report of the traffic I saw from the bus window on my way back and forth from the institute or the market. But it was invariably so lame, so half-hearted and obviously half made-up that Noe eventually ruled that I didn't have a driver's sensibility and was better off telling her about my fellow passengers on the bus. That was much more fun. I like to think that never learning to drive saved me a lot of ball ache. I would have let everyone overtake me, left, right, and center. Boy, it would have driven my wife nuts, me calmly waving on my aggressor.

Back to 1982. Once Noe had finished her traffic update, we would hang up and I would draw in bed. The rest-and-recuperation instruction manual they'd given me in the hospital was too boring to actually read, so I'd asked my night nurse, AKA my wife, and she gave me the gist of it:

Forbidden to work

. And that is how I came to spend my recovery period drawing, a hobby I'd loved as a child, and something I'd spent almost my entire adult life putting off. I soon realized that every time I had a pencil in my hand I'd draw houses. Design them, if you like. All those months spent cooped up in the house of my childhood, adolescence, and adult life (more or less on the spot where I'm writing this now) convinced me I should have been an architect. Architects have the sensibility of an artist, a pinch of philosophical coherence, a healthy dose of opportunism and even their share of scientific rigor on a basic, structural level (the level that stops houses falling down on top of them). But more than all this â and in radical contrast to anthropologists â the work of architects actually serves a purpose.

*

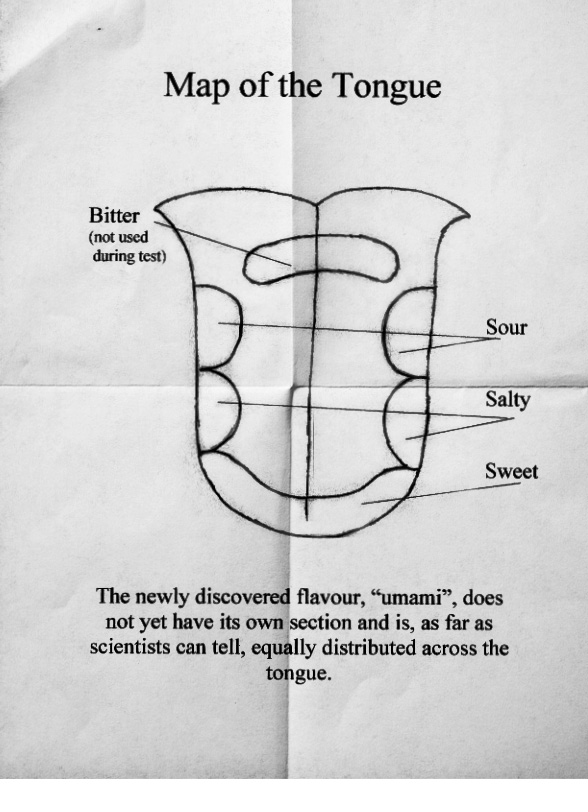

Umami starts in the mouth, in the middle of the tongue, activating salivation. Your molars wake up and feel the urge to bite, beg to move. Not that different in fact, albeit less powerful, from the instinct that drives your hips to move almost of their own accord during sex. In that moment, you only know how to obey your body. The body knows what needs to be done. Chomping is a pleasure, and umami is so darn chompable. Chompable isn't a word, but I don't like chewable. Chewable is what they call those vitamin C tablets. Chompable seems more ad hoc to me, more of a treat, more sinful. Or, as Agatha Christie would say, âdelish'

.

In cookbooks they use the word ârich' to describe umami. I like ârich' but it doesn't translate well into Spanish, because in English it connotes something complex, filling, satisfying, while

rico

just means tasty.

If we delve back to the beginning, perhaps umami doesn't start in the mouth at all, but rather as a craving, at first sight.

*

I dug out a letter I wrote to Noelia from Madrid on July 21 1983.

All I can say, my love, is: Bravo to me! I've made a friend! He's a philosopher. He was leaving the library the other day at the same time as me. Next thing I knew he'd crossed to my side of the street, and we went on like that for twenty minutes, until we reached the same block, both of us suspecting the other of following him. Later we laughed about it, of course: it turns out we're neighbors. He's Spanish and he's called Juan (aren't they all?). Best part is he's just as lonesome as I am because he recently came back from a long exile in Mexico. We've got into the habit of going for a drink

â

or four

â

when the city heats up. Yesterday I asked him where I should go to buy some bathing trunks, because I'm thinking of making the most of the dead hours (so many hours without you!) to learn how to swim. That would be nice, wouldn't it? If I do learn, when I get back, we'll go to Acapulco. We'll go even if I don't learn. I'm craving the sea like never before. It's Madrid's heat (dry as dry can be). It leaves me KO. Anyway, the point is, my Noe, that Juan answered my bathing-trunk query like this: âIn Madrid they've hit upon the ultimate ontological proof, and it goes like this: “If it exists, you'll find it in the Corte Inglés.

”

'

*

I was always grateful to Noelia for not filling our house with archetypal cardiology paraphernalia. In some egocentric etymological retracing of the Latin word

cura

, Mexico's âcurers' seem to think their role also includes âcurating'. Nine out of ten of the doctors we knew regurgitated, ad infinitum, exactly the same exhibition in their offices: âMexican Paperweights â a retrospective'.

Handing out paperweights is an elegant way to take the register at conferences, and they come in all shapes and sizes: glass paperweights (usually pyramid-shaped); copper paperweights (boasting BajÃo-style motifs); hard plastic paperweights (in the shape of a pill); rubber foam paperweights (always anatomically graphic: the heart and all its nooks and crannies, with the name of some drug written in florescent type under the alveoli); rock paperweights, brass paperweights, aluminum paperweights. Paperweights that have nothing to weigh down, because even doctors have had to get with the times and start using computers. And scattered around these gallery pieces we find the accompanying explanatory exhibition texts in the form of diplomas, photos of dogs and children, odes to the Beatles, Mexican flags, gifts from patients who, having faced the light at the end of the tunnel and then been brought back, become remarkably magnanimous (metal knights, little painted plaster saints). One recently recovered patient gave Noelia a gold charm in the shape of heart. She had it melted down and turned into earrings. Truth be told, we weren't entirely innocent of the curating crime ourselves: we too collected our fair share of superstitious figurines, although that was during the Year of Reproduction.

The reason I'm thinking about this â about the aesthetics of doctors' consulting rooms â is because I've spent the whole week seeing doctors. What can I say? Going to hospital isn't what it used to be. To start with, it's no longer my friends who look after me, but rather their putative children. They respect me because they knew who my wife was, but I can't find it in me to respect them, because none of them seem old enough to shave, let alone treat me. It's not what it used to be because back in the day a trip to the hospital meant time away from the institute: a day off. It's not what it used to be because back in the day I would walk out of there with my ego well and truly boosted (the doctors would compare me to the most virile flora and fauna: an oak! A bull!). Nowadays I leave bewildered, afraid I've been hoodwinked; the same feeling you get after talking to a plumber. None of that flora or fauna stuff: I'm just told in the most mechanical of terms that this or that pipework is blocked.

It's not what it used to be because before, after my appointment, I would go up to Cardiology and sit in my wife's little waiting room: to make her uncomfortable, for a laugh, of course, but also to marvel at that other personality of hers, that other person Noelia was at work. So mine, and yet â it was clearer there, with her in her medic's coat, than in any other place â so irrefutably only hers, so beyond me, so much something other than what we were together. In flora-and-fauna terms, an autotroph.

*

Anchovies, tomatoes, and Parmesan cheese all contain glutamate. That is, they are umami-y. The same with chicken and beef, Worcestershire sauce, kombu seaweed, some hellish spread called Marmite which we tried in England (I hated it, Noelia loved it), mushrooms, and â though only on the inside â our wedding rings (both my ring, which I wear on my finger, and Noelia's, which is tied around my neck with a piece of embroidery thread Linda gave me from her sewing kit the other day at the Mug). Now I wear it like Linda does: like a necklace. On the inside of the rings â which are both gold, because deep down we were traditionalists â it says:

Umami, 5-5-1974.

We got married in Morelia, with my tiny family and the whole army of Vargas cousins. They gave us dishware, vases, and a German Shepherd which we passed off to the first nephew who said âI'll take it!' They also took a ton of pictures, which we keep in a box. They're color slides. On our tenth or maybe twentieth anniversary we projected them onto a wall while our friends drifted around the house sipping martinis.

On our wedding day, Noelia wore white flowers in her hair but a pink dress, which not one of her aunts failed to comment on. Preempting their disapproval, I wore a white suit to compensate. They didn't appreciate that either. It had bellbottoms. My mustache was bushy enough for a bird to nest in. What bad taste we had in the seventies, and how shamelessly we wore it. I'm sure if I got out those slides now I'd be scandalized myself by those aunts' outfits.

Another option we considered for our rings was to engrave them with the word

Bonito,

then the date. The idea came to us because it was in the scales of the bonito fish that they first identified monosodium glutamate, which is the salt umami is made from. What's more, the word perfectly summed up our relationship:

bonito

, meaning lovely, meaning beautiful. But in the end we threw that option out the window and opted for the âless pretentious' umami. Go figure.

*

Noelia liked the color pink and not only wore it on her wedding day, but pretty much every day (The Girls, too, when they came along). Pink shoes, pink skirts, even a bag in a hideous Barbie pink; the kind the humanitees can't abide. They've outgrown it. If the humanitees ever wear pink, it has to be Mexican pink. The humanitees, at least in springtime, wear a strict Luis Barragánesque palette: yellow, white, Mexican pink. The rest of the year they wear dark clothes in shiny materials that completely outshine them. Nothing, on the other hand, could ever dull Noelia's natural sparkle. If this were one of those pretentious academic articles, like the ones I used to be an expert in, I'd say, âNothing diminished her intrinsic luminescence.'

*

My first article on umami came out in September 1985 and was, of course, spectacularly ignored. The earthquake probably played some part in this, but it's also true that there's barely a soul on the planet who reads the institute's journal. In fact, judging by the amount of typos, I'm not even convinced the editors read it. They take years to publish something, and when the time finally comes their presentation is mind-blowingly bad.

âLove, I think bad tends to mean good these days.'

âAnd how would you know?'

âThere are a lot of kids in the hereafter, Alfonso, if only you could see.'

âSuicides?'

âCar accidents, mostly.'

*

Since tipping â that most healthy of customs â doesn't exist in the academic world, we settle for citations. As an academic, you can assume, more or less with good reason, that if you did a good job someone will eventually quote you. Personally, I'd rather get tips. Although, having said that, one of the best things that ever happened to me was thanks to a citation. I was quoted by Doctor Nakahara, a student of Doctor Kikunae. Kikunae was the first man to isolate monosodium glutamate, at the beginning of the century in the University of Tokyo. That is, the first man to discover and name umami. Well, Nakahara was one of his most faithful disciples and he quoted me, not in an academic paper, but in a biographical article he wrote to pay reverence to his teacher and to demonstrate that he was famous even in the Third World, all the way over there in Mexico. And thanks to that quote we struck up a pen-friendship so solid only the invention of the email could finish it off. In one of our correspondences, Nakahara sent me this clipping:

When the house half collapsed in 1985 and we ended up having to write off the whole building, move to Morelia for a year, and come up with a new âlife project', it occurred to me to dig out the sketches I'd made during my period of convalescence and convince my wife that we should throw ourselves into converting what was left of the house into something else entirely: a set of houses we could rent. And that's when we discovered that the inordinate quantities of painkillers I'd consumed during my recovery had led me to somewhat overestimate my artistic ability. But Noelia, who spent the whole of eighty-six in a private clinic we'd set up in her cousin's house, seeing patients who were all, in one way or another, relations of hers, said, âDo what you like, love, just get cracking so we can go back to Mexico City.'