Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (40 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

If the crowd starts chopping when you’re in town, don’t panic. You can do this. It takes very little coordination. Just raise your right arm, extend your hand and hold it flat and perpendicular to the ground, then bend your arm at the elbow. Then bring your forearm back up to its original position. If you’re not sure about your pace, keep an eye on the guy to the left or right of you and follow his lead.

Sports in (and around) the City

The Ty Cobb Museum

461 Cook St., Royston, Georgia

You may have heard that the Georgia Peach’s bite was as bad as his bark. Well, here’s your chance to do a little firsthand research. The Ty Cobb Museum houses, among other peculiarities, Cobb’s dentures, which fetched $7,500 at a Sotheby’s auction in 1999. Now, that’s a bite…. we mean bit … of baseball trivia you weren’t expecting.

We were also impressed to find Cobb’s Shriner’s fez and one of his original fielding gloves. As you might have guessed, Cobb’s mitt was smaller than the Ken Griffey Jr. model Kevin still wears.

The museum is about one hundred miles northwest of Atlanta. From Atlanta, follow Interstate 85 to Highway 17 south to the center of Royston. The museum is inside the Joe A. Adams Professional Building of the Ty Cobb Healthcare System and is open year-round.

After our visit we followed Highway 17 South to nearby Rose Hill Cemetery, where we found Cobb’s mausoleum. We peeked through the door to see his vault and those belonging to his mother, father, and sister but that’s as close as we got to his corpse. Honest. In life, Tyrus was a notorious bad-ass. And his mom shot his dad to death as he sneaked through the bedroom window one night. Those are three ghosts we didn’t want messing with us.

If you think the Chop disparages Native American culture, then we suggest not partaking in it. Or, you could get up and visit a concession stand or restroom. Unfortunately, however, the Chop is usually invoked at a key moment in the game, so you may miss a rally if you employ this avoidance mechanism.

This cheerleading squad is composed of perky young ladies who rev up the crowd in a variety of ways. They perform on the plaza before games, provide between-innings entertainment, fire T-shirts into the crowd, lead fans in singing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” and mingle with fans in the stands. We generally don’t need cheerleaders to have a good time. In fact, they usually detract from our enjoyment of the game. But we both agreed that these ladies were a nice addition to the park. Maybe it was the Daisy Duke shorts they were wearing, or maybe the southern drawl with which one of them called Kevin “sugar” when he asked if she’d pose for a picture with him. We’re still trying to figure it out.

You’re in the Deep South, so don’t be surprised when the

Dukes of Hazzard

theme song plays over the Turner Field sound system, much to the pleasure of the fans in attendance.

Desperate to find a Braves super-fan, we were on the lookout for Uncle Jessie or Boss Hog, but all we spotted were the aforementioned Daisy Dukes. We’re not complaining.

Cyber Super-Fans

- Talking Chop

This site’s lively message board is for Brave souls only.

- Braves Blast

This site bombards fans who just can’t get enough Braves content.

Kevin Almost Goaded One of Our Friends into Getting Arrested

During our visit to Hot-lanta we stayed with Kevin’s friend Mike just outside the city. And Mike was happy to meet up with us at the game and to let us sit in his company’s Field Box seats in Section 122. These were good seats, just a dozen rows from the field behind third base.

Upon arriving, Mike introduced us to one of his coworkers who had accompanied him to the game, a Southern gent by the name of Richard Cassinthatcher IV. Rich identified himself as a huge baseball fan, said that we were living his dream, and then subtly mentioned what a thrill it would be for him if we dropped his name somewhere in the Atlanta chapter, since he’d be watching the game with us and all. A few beers later, Rich began overtly pleading with us to include him in our Turner Field chapter.

“I could do something crazy if you’d like,” Rich said, starting to untuck his shirt, toward what end we weren’t sure. “Just tell me what it takes.”

With a name like Cassinthatcher, he had us at “hello,” but we didn’t tell him that.

“Just tell me what it takes,” he said. “Do you boys want another round of beers? How ’bout I buy you boys another round? Would that get me in the book?”

“It would be a good start,” Kevin said.

“Certainly couldn’t hurt,” Josh agreed.

So Rich bought another round of Sweetwater 420s.

“How are those beers treating you boys?” he asked us a moment later.

“They’re treating us well,” Josh said.

“Thanks,” Kevin added.

“So am I in?” Rich asked. “Am I in yet?”

“Well, it’s going to take more than that,” Kevin said, shaking his head. “If we start putting people in the book just for buying us beers … well … that sets a dangerous precedent.”

“I see,” Rich said, nodding his head. “I see, you’re right. It’s got to be more than that. I have to

do

something right?”

“Right,” Kevin said. “Something …”

The next thing we knew, Rich had unbuttoned and removed his shirt, even though it was a chilly night by Atlanta standards.

“I’m going out there,” Rich said.

“On the field?” Josh gasped.

“If that’s what it takes. I want to make it into this book and that’s probably my best chance.”

“Probably,” Kevin said. “You might as well make the most of your opportunity.”

“One more beer, then I’m going.”

At this, Josh shot Kevin a withering look. But Kevin leaned over and said, “Don’t worry, he’d have to drag me with him. I’ll take him down before he gets out of our row.” And that made Josh feel a little bit better.

Rich drank his beer, then loosened his belt buckle, and started untying his shoes. “As long as I make it out there, I’m in, right?” he asked.

“Right,” Kevin said, “as long as you make it out to second base.”

“Second base?” Rich said, measuring with his eyes the distance between his seat and the cornerstone sack.

“Yeah,” Kevin said. “You’d better slide, too, just to be sure. Now-a-days a lot of people are running on the field, but most of them don’t make it to second. And barely anyone slides. If you slide into second, we’ll definitely put you in.”

“Wow,” Rich said, processing this new information. “I’d better have another beer first. And maybe a jumbo dog. I didn’t know I had to make it all the way to second.”

This went on all night. Each time Rich was ready to streak his way into the pages of

The Ultimate Baseball Road Trip,

Kevin upped the ante just enough to make him reconsider.

Finally, after Kevin suggested in the top of the ninth that Rich run circles around Jason Heyward at first base, our friend gave up. “I’m starting to think I’m not going to make this book no matter what,” he said.

“Probably not,” Kevin agreed.

“Tarnation,” Rich said. And he finally put his shirt back on.

Later, as we waited for cabs, he asked us one more time, just to be sure. “Did I make the book, boys?”

“Sorry,” Josh said.

“Almost,” Kevin said. “But not quite.”

Well, Rich, this one’s for you. As it turned out, nothing else too memorable happened to us while we were in Atlanta—Josh lost his Allegra and had a bad allergy day, and Kevin spilled boiled peanuts all over the upholstery of our rental car, but that was it. You made it!

TAMPA BAY RAYS,

TAMPA BAY RAYS,TROPICANA FIELD

Catwalk Baseball in the Thunder Dome

S

T

. P

ETERSBURG

, F

LORIDA

250 MILES TO MIAMI

480 MILES TO ATLANTA

930 MILES TO WASHINGTON

940 MILES TO CINCINNATI

T

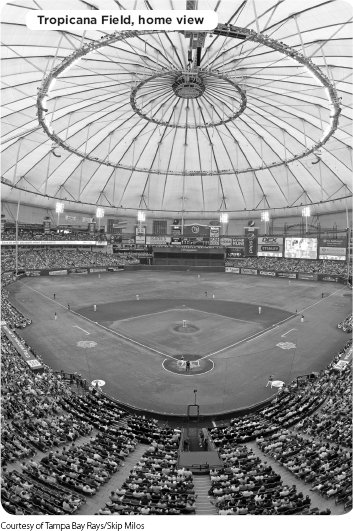

ropicana Field was designed to provide as close an approximation of an old-time ballpark as possible. The fact that the field exists within a domed building hampers this effort considerably, however. But it is admirable that the Rays identify their home as Tropicana Field and not Tropicana Dome, and that in some regards the facility succeeds in achieving a ballpark atmosphere, despite its artificial grass, roof, and rings of spiraling catwalks. At ground level “the Trop” looks like a bona fide baseball field, whereas all of the other domes we’ve visited resemble vast expanses of indoor space where for some reason born out of necessity or madness people play baseball.

This real park ethos is due in part to the dirt infield, which is a novelty, considering that before the Trop dome-makers typically painted white outlines on the plastic turf where the infield clay would meet the outfield lawn and called that meager gesture “good enough.” Mixing real dirt with fake grass is not unprecedented in and of itself, but the combination’s longevity in St. Petersburg makes its presence unique. The Astrodome offered just such an infield from 1966 through 1971, as did Candlestick Park (1971) and Busch Stadium (1970–1976).

Also contributing to the ballpark vibe, the Trop’s outfield dimensions are asymmetrical and the outfield wall has several angles, in contrast to the older-generation domes that sported rounded, symmetrical outfield fences. The Trop’s configuration—with left-center deeper than right-center—is said to resemble the dimensions of Ebbets Field. The outfield in St. Pete is much bigger than the one that once lay in Flatbush, though.

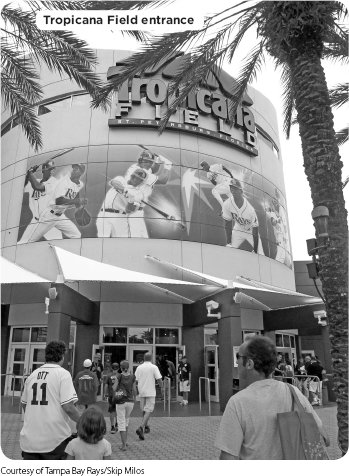

Further channeling Ebbets, the five-story rotunda at the Trop’s main entrance was built from the very blueprints once used in the construction of the Superbas’ old yard. The Mets, you may recall, also tip their caps to their Senior Circuit predecessors with an Ebbets-inspired rotunda at Citi Field. On the floor of the Trop’s rotunda lies a giant baseball laid into the floor. Models of actual rays—which are a type of saltwater fish in the shark family—hang from the ceiling. We’re pretty sure they didn’t have those at Ebbets. The structure may be the same, but here’s betting the rotunda in Brooklyn was classier, with its marble floor and crystal bats hanging from its ceiling.

But there is plenty else special about Tropicana Field, which has, in fact, like a slugger on steroids, gotten better with age. When the team rolled out first-generation Devil Rays—as the team was known until a rebranding in 2008—like Fred McGriff and Bubba Trammell, the Trop sported old-school Astroturf. But in 2000 the team uprooted the original plastic mat and switched to cushy FieldTurf. The Trop was a leading player in the popularization of this second-generation synthetic playing surface that combines blades of longer-than-normal plastic grass with a patented mixture of sand and ground rubber that simulates the dirt that normally exists beneath ballpark sod. The field proved more forgiving to diving players and provided truer bounces than Astroturf. Following the Rays’ lead, many NFL teams, colleges, and Japanese League baseball teams have since installed FieldTurf. Its only other use in big league baseball was at Rogers Centre, but that facility switched to a new-and-improved breed of Astroturf in 2010. In 2011, the Trop switched back to a new generation of Astroturf called Astro-Turf GameDay Grass 3D60H that some claim provides the truest bounces yet. Still, it ain’t real grass.

Kevin:

There’s gotta be a genetic engineer who can design grass that grows indoors.

Josh:

That, and only that, is what our nation’s best scientific minds should be devoting their labors to.

Kevin:

If we don’t do it, the Chinese will.

Josh:

This may well be our generation’s Sputnik moment.

While the roof may not appear exceptional at first, it adds a new wrinkle to the lineage of dome evolution. When

the Rays win, it lights up bright orange, casting an eerie glow over fans as they head home.

Josh:

My friend Joe would love this. He only wears orange.

Kevin:

It looks like a giant pumpkin.

Josh:

Yeah, on most days Joe does too.

Kevin:

No, this looks like a

rotten

pumpkin. The backside’s all caved in.

Josh:

Joe’s backside is nothing to brag about either.

The slope isn’t due to a shortage of roofing materials but is by design. It reduces the volume of air inside, saving on air-conditioning bills and more importantly helps to make the building about as hurricane-proof as a dome can be. The roof is supported by cables and four catwalks that spiral toward the top. Unfortunately the lowest two catwalks interfere with batted balls fairly often. This is not a high dome at 225 feet above second base and just 85 feet above the centerfield wall. Tampa Bay players like Jose Canseco and Carlos Pena both learned this firsthand when they managed to hit balls (in 1999 and 2008, respectively) into the second catwalk—or “B Ring”—that never came down. Both sluggers were awarded automatic doubles, which the local ground rules allowed for at the time. In 2006 Jonny Gomes hit a ball into the B Ring that rattled and rolled around for nearly twenty seconds before dropping straight down into the glove of patient Toronto shortstop John McDonald for the longest-developing pop-out in baseball history. But Josh’s favorite “catwalk moment” occurred in 2002 when Boston’s Shea Hillenbrand won a game for the Red Sox with a ninth-inning grand slam that hit a catwalk in left and bounced all the way back to the infield. As for Kevin’s favorite catwalk dinger, it was the very first. Edgar Martinez went deep off the D ring in 1998 to introduce a whole new sort of homer to baseball tradition. According to local ground rules, hitting the C or D rings still results in a home run but the rules have changed regarding the other two rings as we’ll elaborate on later in the chapter.

Kevin:

Homers were more romantic when they used to disappear into the bleachers.

Josh:

Is this Wiffle Ball or baseball?

Kevin:

Too late to raise the roof now.

The concourse on the first level is colorful, festive and wide enough to accommodate the meager crowds that have traditionally turned out for the Rays. An arcade keeps the kids busy and a number of drinking establishments, food courts, and shops cater to the adults. Clearly, the Trop was designed to get people into the park early and keep them late. As such, the facility has been dubbed a “mallpark” by some fans.

The dome was constructed by the city of St. Petersburg at a cost of $130 million in the late 1980s specifically to lure an MLB team to town. At first, the Chicago White Sox were regarded as a potential suitor for the facility, but those talks were squashed when the Pale Hose secured a financing deal in their own back yard to construct U.S. Cellular Field. Thus, it was without a team that the Suncoast Dome opened for business in 1990. Shortly thereafter, the Seattle Mariners and San Francisco Giants kicked the tires on the dome before reaching stadium deals to remain in their current cities. Then, St. Petersburg vied for a team in the 1993 expansion but lost out to Miami and Denver. Hoping a rebranding might help, St. Pete renamed the facility the Thunder Dome in 1993 to coincide with the arrival of the NHL’s Tampa Bay Lightning, an expansion team that took to the ice beneath

the big top for three years while awaiting construction of the St. Pete Times Forum. For a while it looked as though the facility might never succeed in attracting a baseball team and might just be relegated to a lifetime of hosting Arena Football and auto shows, but then the hopes of Sun Coast hardball fans came true. The 1998 expansion awarded baseball’s twenty-ninth and thirtieth teams to Phoenix and St. Petersburg. And shortly after, the dome underwent a $70 million makeover to make it fully big league compliant. Then, Tropicana swooped in with a $45 million, thirty-year naming rights offer.

It’s a shame that in the years since, Tampa Bay residents haven’t supported their baseball team better. Attendance has remained embarrassingly low since the team drew 2.5 million fans during its inaugural season. Even in the Rays first-place seasons of 2008 and 2010 they failed to average more than twenty-three thousand fans per game and finished in the bottom third among the thirty teams in overall attendance, drawing just 1.8 million a season. Some say the dome shouldn’t have been built across the bridge from the larger city of Tampa. Like they say, “location, location, location.” But is a twenty-mile drive really that big a deterrent to going to the ballpark, we ask?

Another popular theory to explain why the Rays lack an enthusiastic fan base points to the fact that Florida is full of transplants from up north, older residents who grew up rooting for other East Coast teams and who still follow them, instead of the Rays. Tampa Bay, in particular, is Yankee Country, owing to an on-again, off-again Grapefruit League affiliation with the Bronx Bombers that dates back to 1925.

While we were tempted to wonder whether part of the problem might be Tropicana Field and to suggest that an open-air ballpark on the waterfront might draw better, the local fans with whom we spoke did not corroborate this sentiment. They seemed to agree that in steamy Florida a dome is a necessity during the summer months.

After an inglorious beginning—as expansion teams often have—the Rays have, in fact, treated the locals who have been paying attention to a pretty good underdog story. With a smaller bankroll than their AL East counterparts, they’ve used a savvy draft operation and top-notch player development system to their advantage. But their success took a while to develop. On November 18, 1997, the Devil Rays and Diamondbacks held an expansion draft in Phoenix that furnished each team with a roster of thirty-five players. After having watched the cross-state Marlins become the quickest expansion team to ever claim a World Series title just a few weeks earlier, no doubt Tampa Bay fans had high hopes for the Devil Rays that took the field in the spring of 1998. Having taken a Marlin with their first pick in the expansion draft and signed former Marlins coach Larry Rothschild to manage, the Rays hoped to follow in their neighbors’ footsteps. The team drew 45,369 fans to its first game on March 31, 1998, but lost to the Tigers. That crowd still stands as the largest ever for a baseball game at the Trop. Nonetheless, the baby Rays got off to a 10-6 start, becoming the first expansion team to be as many as four games over .500 in its first season. The club came back to earth quickly, though, to finish the year 63-99. But there was no shame in that. Lots of expansion teams stink in their first season. Some manage

to right the ship faster than the Rays did, though. The Rays finished in last place in the five-team AL East in nine of their first ten campaigns, climbing as high as fourth only in 2004 when they reached seventy wins for the first time.