Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) (78 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

H. G. Strauss, who was Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Town and Country Planning, resigned a few days later.

It is not permitted to those charged with dealing with events in times of war or crisis to confine themselves purely to the statement of broad general principles on which good people agree. They have to take definite decisions from day to day.

They have to adopt postures which must be solidly maintained, otherwise how can any combinations for action be maintained? It is easy, after the Germans are beaten, to condemn those who did their best to hearten the Russian military effort and to keep in harmonious contact with our great Ally, who had suffered so frightfully. What would have happened if we had quarrelled with Russia while the Germans still had three or four hundred divisions on the fighting front? Our hopeful assumptions were soon to be falsified. Still, they were the only ones possible at the time.

Triumph and Tragedy

478

5

Crossing the Rhine

General Eisenhower’s Double Thrust into

Germany — British Doubts — Montgomery’s

Advance to the Rhine — The Enemy are Expelled

from the Wesel Bridgehead, March

10 —

Cologne

Captured, March

7

— A Stroke of Fortune for

Twelfth Army Group — The Last German Stand in

the West — Plans and Preparations for Crossing

the Rhine — I Visit Montgomery’s Headquarters,

March

23 —

And Watch the Fly-in, March

24 —

Heavy Fighting at Wesel and Rees — An Evening

in Montgomery’s Map Wagon I Visit Eisenhower,

March

25 —

And Cross the Rhine — Speedy

Progress by the American Armies — The Collapse

of Germany’s Western Front.

D

ESPITE THEIR DEFEAT In the Ardennes,

1

the Germans decided to give battle west of the Rhine, instead of withdrawing across it to gain a breathing-space. General Eisenhower planned three operations. In the first he would destroy the enemy west of the river and close up to it, then he would form bridgeheads, and finally drive deep into Germany. In this last phase there would be two simultaneous thrusts. One would start from the lower Rhine below Duisburg, skirt the northern edge of the Ruhr, which would be enveloped and later subdued, and drive across the North German plain towards Bremen, Hamburg, and the Baltic. The second thrust would be from Karlsruhe to Triumph and Tragedy

479

Kassel, whence there were options northward or eastward according to circumstances.

We had reviewed this plan at Malta with some concern. We doubted whether we were strong enough for two great simultaneous operations, and felt that the northern advance by Montgomery’s Twenty-first Army Group would be much the more important. Only thirty-five divisions probably could take part, but we held that the maximum effort should be made here, whatever its size, and that it should not be weakened for the sake of the other thrust. The matter was keenly argued by the Combined Chiefs of Staff. General Bradley

2

attributes to Montgomery most of the pressure which was brought to bear. This is not a fair assessment.

The British view as a whole was that the northern thrust, with its consequences to the Ruhr, was paramount. In a second respect also we questioned the plan. We were anxious that Montgomery should cross the Rhine as soon as possible, and not be held back merely because German forces were still on the near bank at some distant point.

General Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff, came to Malta and gave us assurances. Eisenhower has said in his official report, “The plan of campaign for crossing the Rhine and establishing a strong force on the far bank was, thanks to the success of the operations west of the river, basically the same as that envisaged in our long-term planning in January, and even before D-Day. The fundamental features were the launching of a main attack to the north of the Ruhr, supported by a strong secondary thrust from the bridgeheads in the Frankfurt area. Subsequently offensives would strike out from the bridgeheads to any remaining organised forces and complete their destruction.”

3

In terms of divisions we were evenly matched. In early February Eisenhower and the Germans had about eighty-

Triumph and Tragedy

480

two apiece; but there was a vast difference in quality. Allied morale was high, the Germans were badly shaken. Our ranks were battle-trained and confident. The enemy were scraping up their last reserves, and in January Hitler had sent the ten divisions of his Sixth Panzer Army to try to save the oilfields of Austria and Hungary from the Russians. Our bombing had grievously injured his factories and communications. He was desperately short of petrol, and his Air Force was only a shadow.

The first task was to clear the enemy from the Colmar pocket. This was completed at the beginning of February by the First French Army, helped by four American divisions.

More important, and leading to a long and arduous battle, was Montgomery’s advance to the Rhine north of Cologne.

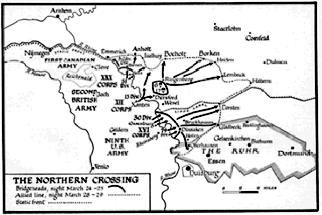

A thrust from the Nijmegen salient by General Crerar’s First Canadian Army, composed of the XXXth British and IId

Triumph and Tragedy

481

Canadian Corps, began on February 8, and was directed southeastward between the Rhine and the Meuse. The defences were strong and obstinately held, the ground was sodden, and both rivers had overflowed their banks. The first day’s objectives were reached, but then the advance slowed down. The difficulties were immense. Eleven divisions opposed us, and we did not capture the strong-point of Goch until February 21. The enemy still held Xanten, the pivot of his Wesel bridgehead.

General Simpson’s Ninth U.S. Army, which had been placed under Montgomery’s orders for the operation, was to strike northward from the river Roer to join the British, but they could not cross the Roer until the great dams twenty miles upstream were captured. The First U.S. Army seized them on February 10, but the Germans smashed open the valves and the river downstream became uncrossable until the 23d. The Ninth U.S. Army then opened their attack. The troops opposing them had been weakened to reinforce the battle farther north and they made good progress. As their momentum gathered the Canadian Army renewed their attacks towards Xanten, and the XXXth Corps joined hands with the Americans at Geldern on March 3. By then the right flank of the Ninth Army had reached the Rhine near Düsseldorf, and the two armies combined to expel the enemy from their bridgehead at Wesel. On March 10

eighteen German divisions were all back across the Rhine, except for 53,000 prisoners and unnumbered dead.

Farther south General Bradley’s Twelfth Army Group proceeded to drive the enemy across the Rhine on the whole eighty-mile stretch between Düsseldorf and Koblenz.

On the left the flanking corps of Hodges’ First Army Triumph and Tragedy

482

advanced with the Ninth, and with equal speed. Cologne was captured, with surprisingly little difficulty, on March 7.

The other two corps crossed the river Erft, took Euskirchen, and branched east and southeast. Two corps of Patton’s Third Army, which had already taken Trier and worked their way forward to the river Kyll, opened their major attack on March 5. They swept along the north bank of the Moselle, and three days later joined the First Army on the Rhine. On the 7th a stroke of fortune was boldly accepted. The 9th Armoured Division of the First U.S. Army found the railway bridge at Remagen partly destroyed but still usable. They promptly threw their advance-guard across, other troops quickly followed, and soon over four divisions were on the far bank and a bridgehead several miles deep established.

This was no part of Eisenhower’s plan, but it proved an excellent adjunct, and the Germans had to divert considerable forces from farther north to hold the Americans in check. This brief campaign carried the Twelfth Army Group to the Rhine in one swift bound, and 49,000

Germans were taken prisoners. They had fought to the best of their ability, but were largely immobilised for want of petrol.

I sent Eisenhower well-earned congratulations.

Prime

Minister

to

9 Mar. 45

General of the Army

Eisenhower

Let me offer you my warmest congratulations on the

great victory won by the Allied armies under your

command, by which the defeat or destruction of all the

Germans west of the Rhine will be achieved. No one

who studies war can fail to be impressed by the

admirable speed and flexibility of the American armies

and groups of armies, and the adaptiveness of

commanders and their troops to the swiftly changing

conditions of modern battles on the greatest scale. I am

Triumph and Tragedy

483

glad that the British and Canadian armies in the north

should have played a part in your far-reaching and

triumphant combinations.

Only one large pocket of Germans now remained west of the Rhine. These stood in a great salient formed by the Moselle from Koblenz to Trier and thence along the Siegfried Line back to the Rhine. Opposite its nose was the XXth Corps of the Third U.S. Army, on its right the Seventh U.S. Army, and, near the Rhine, a French group. The Allies attacked on March 15 against stiff opposition. Good progress was made west of Zweibrücken, but east of it the Germans held firm. It availed them little, for Patton had reached the Rhine north of Koblenz, and he turned five divisions southward across the lower Moselle. The stroke cut in behind the salient. It came as a complete surprise, and met feeble resistance. By March 21 it had reached Worms and joined the XXth Corps, which had burst through the bulge south of Trier.