Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends (23 page)

Read Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends Online

Authors: Jan Harold Harold Brunvand

“Your column has too light a tone,” Mr. H. went on, “leading the reader to believe that you don’t take any story seriously.”

I plead guilty to taking most of the wild stories I hear with a grain of salt, R. H. I’m in the wild story business, so it’s my job to doubt. Beyond that, though, I plead innocent to all charges. First of all, yes, I do know about the lawsuits involving mice in Cokes. There are cases and cases of this stuff—and I don’t mean cases of Coke bottles full of mice, but cases brought before courts of law.

In fact, much of my mail asking about bottled mice comes from lawyers or law students who remember studying the suit brought by Ella Reid Creech of Shelbyville, Kentucky, against a Coca-Cola bottler (1931), or Patargias vs. Coca-Cola Bottling Co. of Chicago (1943), or the 1971 case in which 76-year-old George Petalas was awarded $20,000 in a suit against an Alexandria, Virginia, bottler.

Petalas, the

Washington Post

reported, found the legs and tail of a mouse in a bottle of Coke he bought from a vending machine outside a Safeway store. He was hospitalized for three days, and afterward, no longer liking meat, lived on a diet of “grilled cheese, toast and noodles.”

A search of published appeals-court records made in 1976 turned up forty-five such cases, the first in 1914. One can only guess how many similar cases were never appealed or were settled out of court.

Most of the people who tell the mouse-in-Coke legend don’t know the legal history, though. What they do know is a good story, whether it’s told by a friend, neighbor or coworker. The tellers assume that somewhere, sometime, an actual lawsuit was brought against a soft-drink bottling company.

So while the lawsuits are real, the oral stories are not, because they are so far separated from the original facts that they’ve turned into folklore. In this way, a story can be both an actual event and a legend. And the mouse-in-Coke legends, like most urban legends, have lives of their own completely separate from the facts.

What has occurred, I believe, is something like this: The theme of foreign matter contaminating food is a popular one in urban legends. And “Coke” has become virtually a generic way to refer to soft drinks. So the legends get started, and gain credibility from lawsuits that people vaguely remember in which mice were said to be found in soda bottles. And naturally, it is usually Coke that is mentioned in the legend—whether or not the original suits were against Coke.

As the legend spreads by word of mouth, the trauma is exaggerated, the drama heightened, and the size of the settlement grows. The end result is that indignation against the giant corporation that is selling contaminated food is pumped up to a full measure of outrage.

Adapted from my newspaper column for release the week of April 11, 1988. Since then numerous further lawsuits involving mice (or other foreign matter) found in soft-drink bottles (or other food containers) have been reported. Some of the incidents proved to be hoaxes, suggesting that some people are either acting out a story they’ve heard, or trying to repeat the success of a lawsuit they’ve read about. The problem of mice contaminating food is universal and age-old. In William R. Cook and Ronald B. Herzman’s book The

Medieval World View

(1983), an Irish monastery’s rules for dealing with the situation are quoted: “He who gives to anyone a liquor in which a mouse or a weasel is found dead shall do penance with three special fasts…. He who afterwards knows that he has tasted such a drink shall keep a special fast.” The Irish monks also received specific advice about how to handle “moused” food: “If those little beasts are found in the flour or in any dry food or in porridge or in curdled milk, whatever is around their bodies shall be cast out, and all the rest shall be taken in good faith.” In other words, “Just eat around it, brothers.”

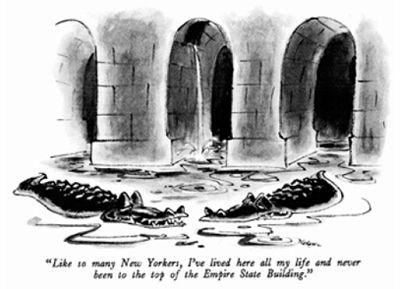

“Alligators in the Sewers”

FLUSHING A PIPE DREAM

GATORS IN NEW YORK SEWERS

New York—like Capt. Hook in “Peter Pan,” John T. Flaherty is dogged by crocodiles and, in addition, alligators. Flaherty is chief of design in the New York City Bureau of Sewers, but he is also the resident expert on the most durable urban myth in the history of cities, of reptiles or of waste disposal.

“Dear Sirs,” writes a correspondent from Stockholm, where sewers are called cloaks, “I take the liberty to write to you, since I from many sources have been informed that, for many years, a substantial number of krokodiles have found themselves a suitable athmosphere of living in the cloak tunnels of New York.”

“Dear persons,” begins a letter from a high school student in Wilkesboro, N.C. “Recently I have become very interested in a very uncommon subject, ‘Alligator population in the New York City water system.’”

And a man from Celoron, N.Y., writes: “I disagree with a co-worker whom insists that an alligator which had lived in a sewer system over a long period of time does not change color. I said I believe the pigmentation of the alligator would become much lighter and in some cases turn almost white.”

Flaherty, a good-humored man with an alligator cigarette lighter on his desk, must reply to all these, “No, Virginia, there are no alligators in the New York City sewer system.”

In the “sewer game,” as Flaherty calls it, which is not a glamor business, this has made John T. Flaherty something of a celebrity. There is even a makeshift star on his door and a mock-up of a

Variety

headline that reads, “Flaherty says new alligator in sewer movie is a flimflam and is nothing but a croc.”

Alligators are a small part of Flaherty’s business. His office is filled with blueprints, and his mind is filled with budget estimates for capital expenditures or expenses. There are 6,500 miles of sewer lines in New York City, ranging from 6-inch pipes to monster sewers as big as a small band shell, from brick sewers circa 1840 to concrete structures under construction; these are Flaherty’s daily concern.

© The New Yorker Collection 1987 Lee Lorenz from cartoonbank.com. All rights reserved.

He has worked as an engineer in this business for almost 30 years, and he has no disdain for it. Touring an underground chamber of brick and concrete in Brooklyn, damp and noisy with running water, he said, “A well-functioning sewer is a rather pleasant atmosphere—nice and cool in summertime, warm in the wintertime.” It seems just the place for an alligator, but it is not.

Alligators have become Flaherty’s sideline, and he handles them with flair. The myth is that travelers to Florida adopted the baby reptiles, tired of them and flushed them down the toilet and into the city sewer system, where they grew to immense size.

Perhaps a half-dozen people write to the city every year asking for particulars; once they got a very formal reply, but now they get Flaherty, who uses this opportunity to give vent to his creative impulses.

To a woman from Denver, who asked if it were true that sewer workers carried guns in case of alligator attack: “As the resident expert on all matters relative to subterranean saurians, I can state with authority that there ain’t no such animal. Rumors! How do they start? It is ironic for instance, that you should write of sewer maintenance personnel here in New York carrying .38s to protect themselves from the ravages of rapacious reptiles. Did you know that there are many New Yorkers who believe that all residents of Denver carry .38s at all times?”

To the man from Stockholm, confirming that alligators have been adopted as pets: “I myself was bitten on the little finger of my right hand by one some 25 years ago in the stacks of the New York Public Library building. Please be reassured that the injury I suffered was quite minor, as the alligator in question was quite a little chap whose dentition was of the puniest.”

And to the man from Celoron, who thought alligators would pale below ground: “I could cite you many cogent logical reasons why the sewer system is not a fit habitat for an alligator, but suffice it to say that, in the 28 years I have been in the sewer game, neither I nor any of the thousands of men who have worked to build, maintain or repair the sewer system have ever seen one, and a 10-foot, 800-pound alligator would be hard to miss. Of course, following the thought that you advance in your letter to its ultimate conclusion, perhaps the pigmentation effect has been so radical that they have been rendered invisible.”

Flaherty says there are things living in the sewers, most of them rats. There are also insects and some stray fish; there once was a duck that got stuck in a pipe and flapped about wildly until it found a way out. There have been some bodies and a few gangs that have set up subterranean sewer clubhouses.

There are, however, no alligators because, Flaherty says, there is not enough space, there is not enough food—“the vast majority of it has been, to put it as delicately as possible, pre-digested”—and the torrents of water that run through the sewers during a heavy rain would drown even an alligator.

Article by Anna Quindlen,

New York Times,

May 19, 1982; except for the misnomer “urban myth,” this is an excellent account of the spread of and the response to what is probably the best-known American urban legend. There are, oddly enough, numerous verified published reports of alligators found in unlikely habitats, including some sewers, and even including a story in the

New York Times

of February 10, 1935, describing an alligator pulled from a sewer on East 123rd Street. None of these reports, however, mentions the folk idea of baby pet alligators flushed down toilets. Robert Daley’s 1959 book

The World Beneath the City

includes an interview with one Teddy May, said to have been a New York City sewer commissioner during the 1930s. May claimed that alligators up to two feet long inhabited the sewers until 1937, when he had them eradicated. When I queried John T. Flaherty about this, he replied in his trademark cheerful style, “Yes, Professor, there really was a Teddy May…almost as much of a legend as the New York City Sewer Alligator

[Alligator cloaca novum eboracum]

itself…. [He] was a sewer worker who, in the fullness of time, rose to become a Foreman or, perhaps, a District Foreman…. From what I can gather, Teddy was a very outgoing, ebullient man with a wide circle of friends and an even wider circle of admiring acquaintances. Part of his charm was his undoubted abilities as a raconteur and a spinner of yarns.” The “Alligators in the Sewers” legend has been celebrated in cartoons, comic books, children’s books, art, literature, and films—including

Alligator,

the 1980 movie alluded to in Quindlen’s article. The New York City Department of Environmental Protection, under which the Bureau of Sewers operates, markets T-shirts and sweatshirts picturing an alligator sporting a pair of fancy sunglasses crawling out from under a manhole cover marked “NYC Sewers” and with the caption “The Legend Lives.” In 1993 sculptor Anne Veraldi installed 15 gators made of tiles in a subway station as part of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Creative Stations program. A possible nineteenth-century English prototype for the legend is reported in Thomas Boyle’s 1989 book

Black Swine in the Sewers of Hampstead.

The title says it all.

“The Snake in the Store”

M

arch 31, 1987

Rug shopper ambushed by deadly cobra

Unsuspecting Louise Park was rummaging through a pile of expensive rugs at a ritzy furniture store when she was attacked—by a deadly cobra.

Louise, 24, was rushed to a London, England, hospital after the enraged reptile sank its fangs into her arm. She was released after several days of painful treatment.

Store manager David Ross said the critter must have stowed away in the rugs when they were shipped from India and Pakistan.

November 17, 1989

The rumor is rampant in Springfield [Illinois] and goes like this.

A woman slips into a coat in a local department store and feels a jab in one arm. She assumes she was stuck by a pin.

Later in the day pain sets in, she detects a redness in her arm and goes to a hospital emergency ward for treatment.

Medics find she was bitten by a snake. Police are sent to the store. A search of the coat inventory turns up a snake in a sleeve lining.

Turns out the coat is a foreign product and it’s an exotic snake that slipped into, or was slipped into, the shipment before it left the Orient.

The snakebite victim, depending on which version of the story you’ve heard, was either released after treatment or remains in the hospital in a coma.

No such snake, says the manager of the department store in question. Hospital spokesmen say they have had no such patients. They’ve all heard the story, too, and say it’s a hoax.