Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends (25 page)

Read Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends Online

Authors: Jan Harold Harold Brunvand

“Spider Eggs in Bubble Yum”

B

ubble Yum, the first

soft

bubble gum to come on the market, contains spider eggs; that’s the ingredient that makes the gum so soft and easy to chew. A kid one time fell asleep chewing Bubble Yum, and he woke up with his mouth full of spider eggs. Some people also say the gum causes cancer.

This short-lived rumor appeared and faded away in 1977, just at the time when the Life Savers, Inc., product had become a best-selling new gum. In his 1992 book

Manufacturing Tales,

Gary Alan Fine quotes a variant from Minnesota that claimed the contaminant was spider

legs.

Beyond this, the claim had few variations and almost no narrative development as a true legend. An article in the

Wall Street Journal

on March 24, 1977, detailed the company’s problems with the rumor. In response to the stories, Life Savers placed full-page advertisements in the

New York Times

and other major newspapers, headlining them “Someone is telling your kids very bad lies about a very good gum.” In 1984 satirist Paul Krassner claimed to have invented the Bubble Yum story, as well as the one about worms in McDonald’s hamburgers.

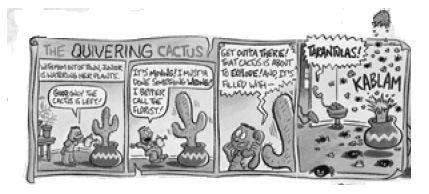

“The Spider in the Cactus”

J

uly 18, 1991

Dear Dr. Brunvand:

I have come across a story that has all the earmarks of an urban legend and thought you might be interested in learning about it.

Last weekend, while visiting my parents in Detroit, my sister, who was also in town from New York, related the following story about her assistant’s friend…. My sister swears this story is true.

My sister’s assistant told her about a female friend who bought a saguaro cactus from an Ikea store in New Jersey. The friend brought the cactus home to her apartment and was very happy with it until one day it started pulsating. She thought this was bizarre behavior for a cactus, so she called several different places to see if “experts” could tell her what was wrong with it. After the public library and a couple of nurseries were unable to help her, she called a botanist at the natural history museum. He told her to immediately take her cactus outside, douse it in gasoline, and set it on fire. My sister’s assistant’s friend did as she was told, and, much to her horror, after she set the saguaro alight, dozens of burning tarantulas crawled out of the charred wreckage of her cactus.

Somehow, this story seems rather farfetched to me. I was wondering if you had heard anything about lethal cacti in the past.

Sincerely,

Sarah P. Beiting

Kalamazoo, MI

W

eek of September 23, 1991

Dear Sarah:

Farfetched? How can you say that? A home-size saguaro cactus, a supply of gasoline in the apartment, and a stampede of burning tarantulas…It sounds just like a typical day in New York to me. And, of course, the cactus technically wasn’t lethal, except to the spiders.

But seriously, folks, we all know this is an urban legend, do we not? In fact, some readers may remember that Kalamazoo is where it all began, at least as far back as my own information on “The Spider in the Cactus” goes.

I’m sure if you ask around in your hometown, Sarah, you’ll find someone who remembers the Kalamazoo version of your cactus story. You see, back in 1989 I received my first American report of the story from a man in Kalamazoo who heard that the plant had been purchased locally at an outlet of Frank’s Nursery and Crafts.

During the next couple of years many other versions surfaced throughout the United States, some mentioning Frank’s, others claiming the cactus had been dug up illegally in the deserts of Mexico or the southwestern United States. Wherever it came from, the wiggling, vibrating, trembling, humming, squeaking, buzzing cactus was usually torched and thus found to be a home for a horde of deadly spiders or scorpions….

Letter from a reader as incorporated into my newspaper column. The prototype for this legend circulated in Europe starting in the early 1970s; a 1990 German collection of urban legends is titled

The Spider in the Yucca Palm.

I give a detailed history of this legend in my 1993 book

The Baby Train,

pp. 278–87, concluding with a brief reference to Ms. Beiting’s letter. During the seven years that the story was popular in this country, I received 65 letters, clippings, or other queries about it. The release of the horror film

Arachnophobia

in 1990 may partly explain the interest in “The Spider in the Cactus” that year. The problems that Ikea, the home-furnishings chain, suffered from the legend were mentioned in

Business Week

for February 11, 1991, with the headline “So, Let’s Go Hunt Alligators in the Sewers.”

Copyright 1998 Children’s Television Workshop (New York, New York). All rights reserved.

“The Poison Dress”

M

y cousin’s cousin who works in Fine Women’s Wear at Neiman Marcus in Beverly Hills told me this “true” story last Thanksgiving. He told me that since Neiman’s has a very lenient return policy, many wealthy women put $10,000 dresses on their charge accounts, wear them once, have them dry cleaned, and then return them to the store for a refund.

Someone at the store told him what happened one time because of this practice before he started working there. After a woman returned a very expensive designer dress, another woman bought the same dress, and she later broke out in a horrible rash while wearing it.

She went to a dermatologist who said he had to treat her skin for exposure to formaldehyde, and so she sued Neiman’s for the doctor’s charge. The store traced the dress to the first woman, who admitted that her mother had wanted to be buried in that dress. But the daughter didn’t want to bury such an expensive dress, so she got it back from the mortician after the funeral service and returned it to the store.

The second woman had been exposed to formaldehyde that soaked into the fabric from the corpse.

I thought this was true until my girlfriend told me just the other day that her grandmother wouldn’t let her buy dresses from thrift shops because of a woman who had died from formaldehyde in a second-hand dress. So this hot new story turned out to be at least 60 years old!

Sent to me in 1991 by a reader in Los Angeles. “The Poison Dress”—also called “Embalmed Alive” and “Dressed to Kill”—was one of the first American urban legends to come to the attention of folklorists. In the 1940s and ’50s several folklore journals described a rash of reports, so to speak, of the story, and some informants remembered hearing it in the 1930s. Often, the woman who “borrows” the dress for a funeral is from an ethnic or racial minority, and she is usually poorer than the woman who sickens and/or dies from wearing the dress the second time. Formaldehyde, which many people encounter only in high school biology classes, is not used for embalming. As for the threat of real embalming fluid, often mentioned in the story, I heard from a Chicago journalist who had asked a mortician about this point in the story. The mortician opened a bottle of the fluid and splashed some over his own face, saying, “Does this answer your question?” The modern legend may derive from older stories about disease-infected blankets or clothing given to native peoples in order to eliminate them. These stories, in turn, may derive from various ancient Greek stories about poisoned or “burning” garments given to someone as an act of revenge. Classical folklorist Adrienne Mayor discusses these background traditions in one article in the

Journal of American Folklore

(winter 1995) and another in

Archaeology

(March/April 1997). Bennett Cerf included an embellished version of this legend in his 1944 book

Famous Ghost Stories,

saying that it was a favorite among New York literary circles of the time.

“The Corpse in the Cask”

S

ome years ago, the father of a friend of mine bought a fairly enormous house in the middle of Bodmin Moor, a sort of Georgian/Regency house built on the site of an older farmhouse.

In the capacious cellars they found half a dozen very large barrels. “Oh, good!” said the mother. “We can cut them in half and plant orange trees in them.”

So they set to work to cut the barrels in half, but they found that one of them was not empty, so they set it up and borrowed the necessary equipment from the local pub. The cellar filled with a rich, heady Jamaican odour.

“Rum, by God!” said the father. It was indeed, so they decided to take advantage of some fifty gallons of the stuff before cutting the barrel in half.

About a year later, after gallons of rum punch, flip and butter had been consumed, it was getting hard to get any more rum out of the barrel, even by tipping it up with wedges. So they cut it in half, and in it found the well-preserved body of a man.

People who died in the colonies and had expressed a wish to be buried at home were shipped back in spirits, which was much more effective than brine.

From Rodney Dale’s 1978 book

The Tumour in the Whale,

pp. 64–65. Dale characterizes this story as a “Whale Tumour Story,” his term for urban legend, despite its being told to him as true by an individual whom he names. Probably it is an English legend derived from the reality that corpses were sometimes shipped home from abroad preserved in barrels of spirits. After Admiral Horatio Nelson fell at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, for example, his body was preserved in a barrel of brandy and sent back to England, with the brandy replaced at Gibraltar with wine. According to legend, some of the wine serving as Lord Nelson’s impromptu embalming fluid was tapped off by thirsty sailors. A similar legend is told in France regarding a corpse found inside a tank of cheap bulk wine shipped from Algeria to France. Supposedly the body of a man either has a knife in its back or a hangman’s noose around its neck. The American equivalent to these stories describes a decomposed body found in a town’s water tank when it is opened for cleaning or to clear an obstruction in the outlet pipe.

“The Accidental Cannibals”

I

can’t vouch for the authenticity of this story. But Ellis Darley of Cashmere [Washington], retired plant pathologist, says it happened to one of his former colleagues in California.

The colleague, another scientist, grew up in Yugoslavia. During World War II, his Yugoslavian friend experienced severe food shortages, which were alleviated by CARE packages from relatives living in the United States.

The food came in tins. It seems that one package arrived without a label. It was a powder, and the Yugoslavian family assumed it to be a food supplement, which was welcomed at that time.

They tried it out on their meal, found it added some zest to the food, and polished off the whole tin.

It was many weeks later that a letter arrived describing the sending of the package.

The letter said that the Yugoslav’s grandmother had died, and that they sent her cremated remains back to her home country in that tin!

Well, she got back home all right.

From the “Talking It Over with Wildred R. Woods” column in the

Wenatchee (Washington) World,

August 27, 1987. Variations of this story are known all over Europe, with the “cremains” being mistaken for an instant powdered drink, soup mix, flour, cake mix, or condiment. In 1990 a BBC radio program included a letter from a listener who claimed his family had mistakenly stirred into their Christmas pudding the cremains of a relative shipped back from Australia, eating half of it before receiving a letter of explanation. A story found in Renaissance sources tells of pieces of the pickled or cured body of a Jew being returned home for burial being mistakenly snacked upon by other shipboard passengers. In modern times, in countries with serious food shortages, there are persistent rumors of human flesh being sold as beef.

“Hold the Mayo! Hold the Mozzarella!”

I

overheard this in line at a grocery store in Tampa, Florida, in November 1988. One teenager said to another, “You know why Burger King is putting out all those free Whopper coupons? The company is going bankrupt. There is a big lawsuit filed against the company in New England. Some employee had AIDS and decided to get back at people by jacking off in the mayonnaise. You can get AIDS eating Whoppers. That’s why they’re giving them away.”