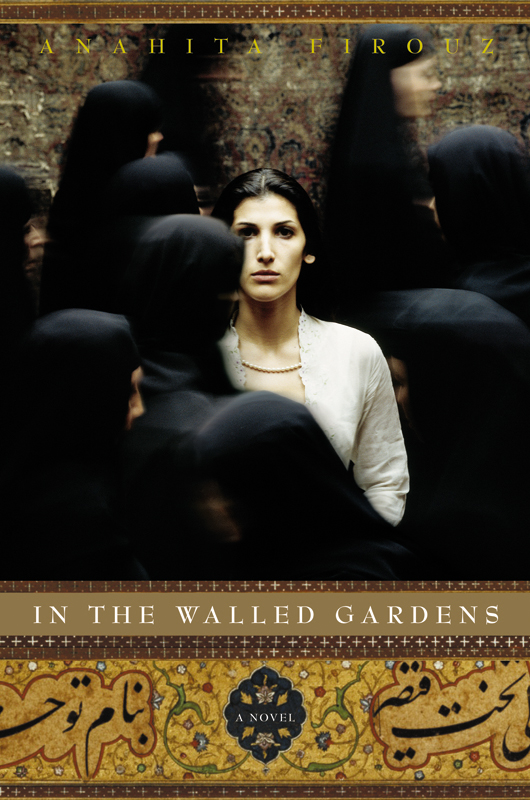

In the Walled Gardens

Read In the Walled Gardens Online

Authors: Anahita Firouz

Copyright © 2002 by Anahita Homa Firouz

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including

information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may

quote brief passages in a review.

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and

not intended by the author.

Four lines in epigraph reprinted by kind permission from Coleman Barks:

The Essential Rumi,

translated by Coleman Barks (with John Moyne and Reynolds Nicholson), published by HarperCollins. Copyright © 1995 by Coleman

Barks. Translation of Sepehri poem reprinted by kind permission from the translator, Karim Emami.

ISBN: 978-0-316-07377-6

Contents

For my daughter and my son,

Anousha & Amir-Hussein

The dust of many crumbled cities

settles over us like a forgetful doze,

but we are older than those cities.

...........................

and always we have forgotten our former states. . . .

M

AULANA

J

ALALEDDIN

R

UMI

I would like to thank the Library of Congress, especially for making available the microfiches I requested from the

Iranian Oral History Project

(Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Harvard). Of all my research, these unpublished interviews with a number of political

dissidents active before the 1979 revolution were invaluable primary sources. I would also like to acknowledge the Carnegie

Library in Pittsburgh.

This story and all its characters are entirely fictional, belonging to a vanished world.

A special thanks to Dan Green and Simon Green, and Judy Clain at Little, Brown.

THE MOSHARRAF FAMILY

Mahastee,

married to

Houshang Behroudi,

with two young sons:

Ehsan

and

Kamran

Nasrollah,

her father

Najibeh,

her mother

Kavoos, Ardeshir,

and

Bahram,

the three older brothers

Tourandokht,

the old nanny

THE NIRVANI FAMILY

Reza,

the son, a Marxist revolutionary

Hajji Alimardan,

his father, deceased, once overseer of the Mosharraf family estates

Shaukat ol-Zamon,

his mother

Zarrindokht (Zari),

the daughter, married to

Morteza Behjat,

with three children

JALAL HOJJATI

,

a radical revolutionary, a friend of Reza’s

THE BASHIRIAN FAMILY

Kamal,

the father, a civil servant and a colleague of Mahastee’s

Peyman,

his son, a university student

T

HE WHITE JASMINE WAS

in bloom. Blossoms were gathered in silver bowls throughout the rooms, and the scent had taken possession of the house. That

night, Mother said, summer would be celebrated with a dinner party on the back veranda. They’d strung up the paper lanterns,

their orbs swaying in the evening breeze. From my bedroom window upstairs I watched the garden, the curve of flower beds,

the gardeners spraying the lawns, fans of water arcing out at sunset.

Dinner would be late. My brothers were having their friends, and I was having mine. At quarter to eight, Father, immaculately

dressed, came out in the upstairs hall and settled down to read yet another version of the rise and fall of our history. Mother

was fretting downstairs, orchestrating our life as usual. She called out to my brothers to bring the stereo system out into

the garden.

My three brothers, not married yet, went out often with a lot of girls and brought many of them home. That summer of my sixteenth

year, I watched them go out into the world and I watched them return. Always triumphant. I couldn’t decide if it was their

freedom that made them that way, or the privilege and certainties of home. I believed in never letting on how much I knew,

preserving power. And secretly I longed to see my life ravaged so I could see it rise up again from its own ashes — a riveting

thought.

I went out into the hall dressed in ivory muslin and pearls for dinner. A manservant ran halfway up the stairs to make a hurried

announcement.

“Sir, madame says it’s Hajji Alimardan! He’s here with his son! They’re waiting in the living room.”

Father, breaking into a smile, said, “What a splendid surprise.” My pulse raced. Reza was back for the first time. I hadn’t

seen him in two years.

We descended, Father telling me as usual how much he missed Hajj-Alimardan, how he’d never understand why Hajj-Ali had suddenly

left his services, the properties and gardens he once oversaw now in decline. How he had been not just an overseer but a confidant,

a friend.

They were in the living room with their backs to us when we entered.

“Hajj-Ali!” Father said, and they turned.

Our fathers shook hands with long-seated affection. Reza, even taller than when I’d last seen him, looked me over, then nodded.

His father still had that strange mixture of rectitude and kindness but looked pale and surprisingly aged. His eyes were misty,

like my father’s as he embraced Reza.

“How are you, my son? Look at you, a man now! How old are you?”

I knew. He was sixteen; he and I had also known each other a lifetime.

Hajj-Ali had come on a private matter. I suggested to Reza a walk in the gardens, and we left, passing through the back doors

to the veranda. We stepped out, the evening revealing itself in a hush. He saw the tables set with white tablecloths and turned,

pride darkening his wide-set eyes, the angles of his clean-shaven face shifting with the light. We went left up the gravel

path toward the arbors, my ivory dress whiter at dusk, like a bride’s. He didn’t say a word. When we got to the trees, he

turned.

“You haven’t changed much,” he said.

I smiled. “You thought I’d got bigheaded? That’s why you never visit?”

“Tonight Father insisted.”

I wanted to ask him why they’d left that summer so suddenly, but looking at him now, I knew he wouldn’t tell. I knew he was

stubborn, reticent, unwavering, that he kept secrets with tenacity and vision.

“You look nearly old enough to be married,” he said.

“This autumn I’m going away to study in England,” I said defiantly.

“Of course, England. Isn’t it good enough staying here?”

“It’s what we’ve all done.”

Suddenly he smiled. “Then what?”

“Then I’ll come back, of course.”

Behind the wall of cypress, we turned into the greenhouse. Passing through the potted orange and lemon trees, he stopped.

“I think Father is gravely ill,” he said.

I flinched. I thought of Hajj-Ali as blessed and immortal. He said his father was at the doctor’s constantly for his heart.

We wended our way out and to the far side of the rose garden. I asked about his school. He named a public school. It was a

rough place and had gangs. “We’re into politics,” he said, his jaw setting suddenly with this. Voices rose from the veranda,

laughter, then someone put on a record. A slow, dreamy summer love song.

He stared at the trees. “You have guests. You should go back.”

“Remember when I taught you to dance?”

“That was another life.”

He said it with a quiet anger, then stared at me, the anger plucked away, his eyes searching my face. The hum of cicadas rose

to a throbbing around us, the leaves above shivering with a breeze that ruffled my dress and hair. He hovered in the shadows

for a moment, then stepped in close. He bent down and, gripping me, pressed his lips to my mouth with a quiet urgency, then

a crushing force, and I felt shaken as if given desire and elation and life forever.

Emerging through the trees to the sweep of lawns, we saw in the distance the house rising, the veranda draped in flowering

wisteria, the spectacle of guests under lanterns. We hovered like phantoms at this distant border, and I thought, That’s what

we are, he and I, a separate world.

“Look! Safely back where you belong,” he said.

We came up along the side of the house. Mother, presiding over her guests, saw us and followed us with her gaze, watching

to see if I would give anything away. She pointed over to my friends. The boys eyed Reza with that who’s-he, he’s-not-one-of-us

look. The girls smiled and made eyes at him. He slipped past them and whispered to me that he had to leave, his father was

waiting.

We found him in the library alone.

“Hajj-Ali, you must stay for dinner!” I said.

“It’s getting late. I get tired quickly,” he said. “We must go.”

Father reappeared and gave Hajj-Ali a large and thick sealed envelope, and we accompanied them to the door. I rushed back

to the veranda.

Mother came up and whispered to me, “You look ashen. As if you’ve seen a ghost. The climate in England will do you good.”

The moon was up, and when the music rose and I was asked to dance, I turned, looking down the lawns at the immense shadow

of trees.

I

SAW HER

for the first time after twenty years, at an afternoon concert of classical Persian music in the gardens of Bagh Ferdaus.

It was an outdoor concert in early autumn. Summer still lingered, the leaves of the plane trees and walnuts brown and withering

at the edges. The sky was over-cast, threatening rain, the afternoon unusually muggy. She wore yellow, the color of a narcissus

from Shiraz. I knew it was her in a split second even after all those years.

The bus had taken forever all the way from downtown. As we crawled north, the mountains loomed closer and closer. The traffic

on Pahlavi Avenue was terrible, even worse when we reached Tajreesh. Two friends who work at the National Television were

waiting outside the gate with tickets. Abbas gave me one and we rushed in. He’s grown a beard recently to go with his political

leanings.

“Classy affair, isn’t it?” he said, pointing.

“It’s going to rain.”

“Lucky you didn’t have to park,” said Abbas.

We walked past the pavilion — a Qajar summer palace — and down the lawns to the concert, which had already started. There

was a crowd and all the chairs were taken, so we stood. Two television cameramen with headsets were recording the event, black

cables snaking by their feet. I watched the old trees at the periphery of the garden and listened to the music. The

santour, kamancheh, nay,

the

tonbak.

My friends wandered and talked. They hadn’t come for the music. When the concert was over, they introduced me to colleagues

who were making a film on old monuments. We strolled back up to the pavilion and stood under the porch, looking out to the

gardens. That’s when I saw her coming up the lawns, the yellow of her suit conspicuous in the crowd, her face unmistakable.

She was talking to friends, and a sudden gust of wind ruffled their clothes. When they left her, I saw an opportunity and

was happy that she’d come alone. Then two dapper men stopped her to talk, and the three of them drew together as if conferring.

From that distance it looked serious.

“Coming?” Abbas asked me.

“I’ll see you by the entrance.”

“Who’s the woman?”

I shrugged and they left to get the car. I whipped around and saw her standing by a sapling, and she seemed distracted, suddenly

distressed. A light rain began to fall and she looked up, squinting, her hair falling back, slithering, let loose, still a

deep brown like chestnuts. Nothing had really changed her in twenty years.

I wanted to go forward and say, Remember me? Reza Nirvani. Son of Hajji Alimardan, overseer of your father’s estates. I knew

she would.

The sky thundered, an eerie color; then suddenly there was hail. The garden turned gray and menacing, shrouded by hail-stones

the size of bullets. She came running in under the roofed porch, her hair and face wet, now just a few feet away from me.

Her eyes, hazel, familiar, were scanning a limited horizon, but she didn’t see me. The crowd pressed in, keeping us apart.

She dropped her program, shook her hair, leaned against the white wall, and took off her shoes, legs still slightly tanned

from the long summer, toenails vivid red. The television crew jostled past us with bulky equipment. People made a dash for

the gate, scrambling into cars. I waited, though I knew I’d lost the moment. Now just a handful of people remained under the

porch, the hail pounding into the lawns.