To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others (24 page)

Read To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others Online

Authors: Daniel H. Pink

Tags: #Psychology, #Business

The outcome was startling. Turner discovered that “80% of the incidental findings were not reported when the photograph was omitted from the file.”

7

Even though the physicians were looking at precisely the same image they had scrutinized ninety days earlier, this time they were far less meticulous and far less accurate. “Our study emphasizes approaching the patient as a human being and not as an anonymous case study,” Turner told

ScienceDaily.

8

Physicians, like all the rest of us, are in the moving business. But in order for them to do their jobs well—that is, to move people from sickness and injury to health and well-being—doctors fare better when they make it personal. Instead of seeing patients as duffel bags of symptoms, viewing them as full-fledged human beings helps physicians in their work and patients in their treatment. This doesn’t mean doctors and nurses should abandon checklists and protocols.

9

But it does mean that a single-minded reliance on processes and algorithms that obscure the human being on the other side of the transaction is akin to a clinical error. As Turner’s study shows—and because of his work, photographs are now being added to Pap smear specimens, blood tests, and other diagnostics

10

—injecting the personal into the professional can boost performance and increase quality of care.

And what’s true for doctors is true for the rest of us. Every circumstance in which we try to move others by definition involves another human being. Yet in the name of professionalism, we often neglect the human element and adopt a stance that’s abstract and distant. Instead, we should recalibrate our approach so that it’s concrete and personal—and not for softhearted reasons but for hardheaded ones. The general problem of road safety in Kenya is abstract and distant. Equipping individual passengers to influence their very own

matatu

driver while he is driving them makes it concrete and personal. Reading a CT scan alone in a room is abstract and distant. Reading a CT scan when a photograph of the patient is staring back at you makes it concrete and personal. In both traditional sales and non-sales selling, we do better when we move beyond solving a puzzle to serving a person.

But the value of making it personal has two sides. One is recognizing the person you’re trying to serve, as in remembering the individual human being behind the CT scan. The other is putting yourself personally behind whatever it is that you’re trying to sell. I’ve seen this flip side in action not in the pages of a social science journal or the corridors of a radiology lab, but on the walls of a pizzeria in Washington, D.C.

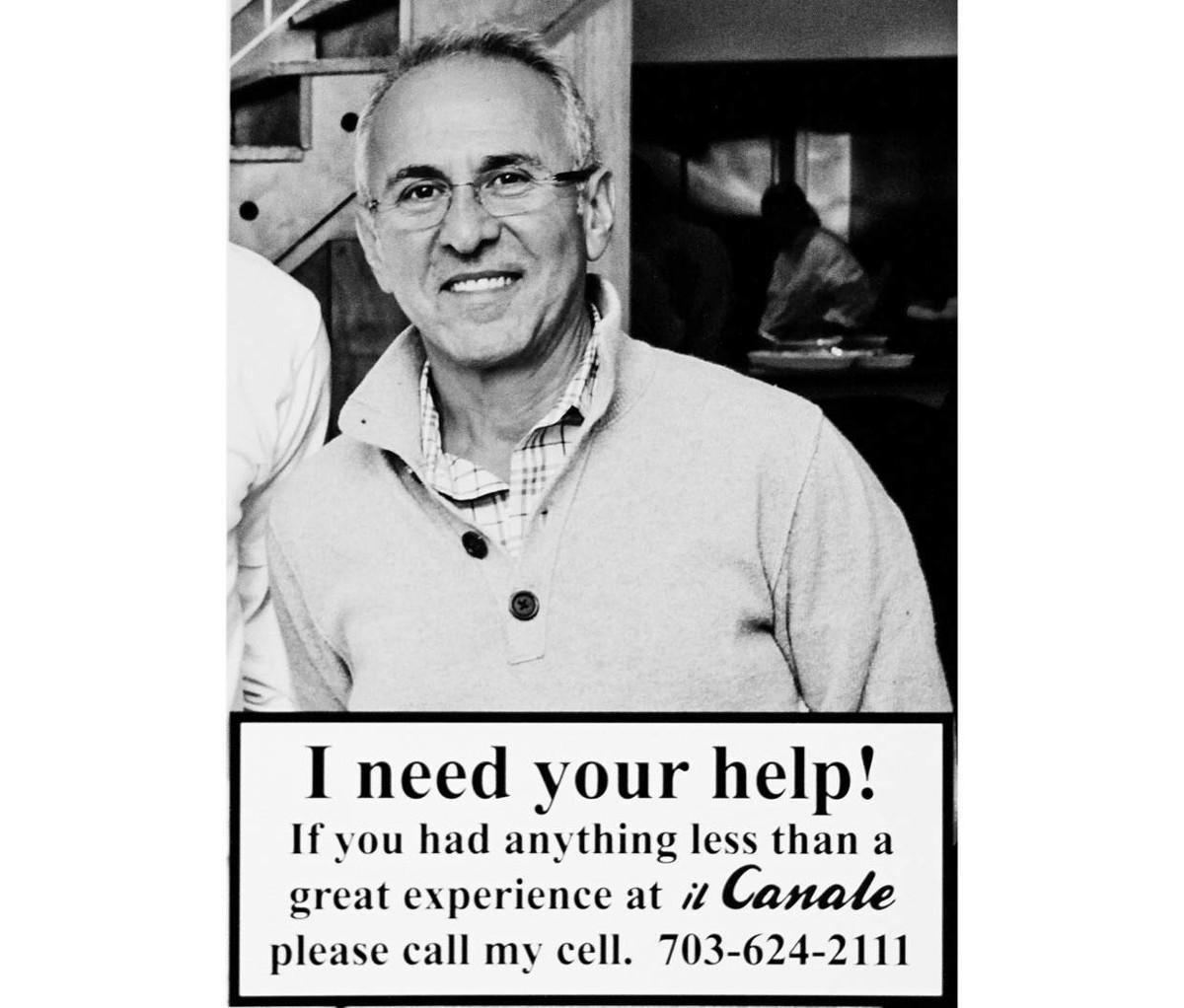

One Saturday night last year, my wife and two of our three kids decided to try a new restaurant, Il Canale, an inexpensive Italian place that had been recommended by friends from Italy. We had to wait a few minutes before being seated. And since I suffer from inveterate pacing disorder, I did a few laps inside the small front lobby. But I halted when I saw this framed sign with a photograph of the restaurant’s owner, Giuseppe Farruggio:

Farruggio, who came to the United States from Sicily when he was seventeen, is in sales, of course. He’s selling fresh antipasti, linguine alle vongole, and certified Neapolitan pizza to hungry families. But with this sign, he’s transforming his offering from distant and abstract—Washington, D.C., is not short on places that serve pizza and pasta—to concrete and personal. And he’s doing it in an especially audacious way. For Farruggio, service isn’t about delivering a calzone in twenty-nine minutes. For him, service is about literally being at the call of his customers.

When I talked with him a few weeks later about the response he’d gotten, Farruggio said that in the first eighteen months he posted the sign, he received a total of only eight calls. Six were from people offering praise—or perhaps testing if the promise was for real. Two came from customers with complaints, which Farruggio used to improve his service. (Dear reader, please do not call Mr. Farruggio’s mobile phone unless you have a bad meal at Il Canale, which in my experience occurs roughly never.) But the importance of what he’s doing isn’t the calls he’s receiving from customers. It’s what he’s communicating to them—namely, that there’s a person behind the pizza and that person cares about whether his guests are happy. Just as putting a photograph alongside the CT scan changes the way radiologists do their jobs, putting his own smiling face and phone number above the front cash register changes the way customers experience Farruggio’s restaurant. Many of us like to say, “I’m accountable” or “I care.” Few of us are so deeply committed to serving others that we’re willing to say, “Call my cell.”

Farruggio’s style of making it personal is characteristic of many of the most successful sellers. Brett Bohl, who runs Scrubadoo .com, which sells medical scrubs, sends a handwritten note to every single customer who buys one of his products.

11

Tammy Darvish, the car dealer we met in Chapter 3, gives her home e-mail address to all of her customers, telling them, “If you have any questions or concerns, contact me personally.” They do. And when she responds, they know she’s there to serve.

Make it purposeful.

American hospitals aren’t as dangerous as Kenyan

matatu

s, but they’re far less safe than you’d think. Each year, about 1 out of every 20 hospitalized patients contracts an infection in a U.S. hospital and the resulting toll is staggering: ninety-nine thousand annual deaths and a yearly cost of upward of $40 billion.

12

The most cost-effective way to prevent these infections is for doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals to regularly wash their hands. But the frequency of hand washing in U.S. hospitals is astonishingly low. And many of the efforts to get more people scrubbing their hands more often have been sadly ineffective.

Adam Grant, the Wharton professor whose research on ambiversion I discussed in Chapter 4, decided to see if he could find a better way to move those working inside hospitals to change their behavior. In research he conducted with David Hofmann of the University of North Carolina, Grant tried out three different approaches to this non-sales selling challenge. The two researchers went to a U.S. hospital and obtained permission to post signs next to sixty-six of the hospital’s soap and hand-sanitizing gel dispensers for two weeks. One-third of those signs appealed to the health care professionals’ self-interest:

HAND HYGIENE PREVENTS YOU FROM CATCHING DISEASES.

One-third emphasized the consequences for patients, that is, the purpose of the hospital’s work:

HAND HYGIENE PREVENTS PATIENTS FROM CATCHING DISEASES.

The final one-third of the signs included a snappy slogan and served as the control condition:

GEL IN, WASH OUT.

The researchers weighed the bags of soap and gel at the beginning of the two-week period and weighed them again at the end to see how much the employees actually used. And when they tabulated the results, they found that the most effective sign, by far, was the second one. “The amount of hand-hygiene product used from dispensers with the patient-consequences sign was significantly greater than the amount used from dispensers with the personal-consequences sign . . . or the control sign,” Grant and Hofmann wrote.

13

Intrigued by the results, the researchers decided to test the robustness of their findings nine months later in different units of the same hospital. This time they used only two signs—the personal-consequences version (

HAND HYGIENE PREVENTS YOU FROM CATCHING DISEASES

) and the patient-consequences one (

HAND HYGIENE PREVENTS PATIENTS FROM CATCHING DISEASES

). And instead of weighing bags of soap and sanitizer, they recruited hospital personnel to be their hand-washing spies. Over a two-week period, these recruits, who weren’t told the nature of the study, covertly recorded when doctors, nurses, and other health care staff faced a “hand-hygiene opportunity” and whether these employees actually hygiened their hands when the opportunity arose. Once again, the personal-consequences sign had zero effect. But the sign appealing to purpose boosted hand washing by 10 percent overall and significantly more for the physicians.

14

Clever signs alone won’t eliminate hospital-acquired infections. As surgeon Atul Gawande has observed, checklists and other processes can be highly effective on this front.

15

But Grant and Hofmann reveal something equally crucial: “Our findings suggest that health and safety messages should focus not on the self, but rather on the target group that is perceived as most vulnerable.”

16

Raising the salience of purpose is one of the most potent—and most overlooked—methods of moving others. While we often assume that human beings are motivated mainly by self-interest, a stack of research has shown that all of us also do things for what social scientists call “prosocial” or “self-transcending” reasons.

17

That means that not only should we ourselves be serving, but we should also be tapping others’ innate desire to serve. Making it personal works better when we also make it purposeful.

To take just one example from the research, a team of British and New Zealand scholars recently conducted a pair of clever experiments in another non-sales selling context. They randomly assigned their participants to three groups. One group read information about why car-sharing is good for the environment. (Researchers dubbed these folks the “self-transcending group.”) One read about why car-sharing can save people money. (This was the “self-interested group.”) The third, the control group, read general information about car travel. Then the participants filled out a few unrelated questionnaires to occupy their time. When they were done, they were dismissed and told to discard any remaining papers they still had. And to do that, they had two choices—a clearly marked bin for regular waste and a clearly marked bin for recycling. About half of the people in the second and third groups—the “self-interested” and control groups—recycled their papers. But in the “self-transcending” first group, nearly 90 percent chose to recycle.

18

Merely discussing purpose in one realm (car-sharing) moved people to behave differently in a second realm (recycling).

What’s more, Grant’s research has shown that purpose is a performance enhancer not only in efforts like the promotion of hand washing and recycling, but also in traditional sales. In 2008, he carried out a fascinating study of a call center at a major U.S. university. Each night, employees made phone calls to alumni to raise money for the school. As is the habit of social psychologists, Grant randomly organized the fund-raisers into three groups. Then he arranged their work conditions to be identical—except for the five minutes prior to their shift.

For two consecutive nights, one group read stories from people who’d previously worked in the call center, explaining that the job had taught them useful sales skills (perhaps attunement, buoyancy, and clarity). This was the “personal benefit group.” Another—the “purpose group”—read stories from university alumni who’d received scholarships funded by the money this call center had raised describing how those scholarships had helped them. The third collection of callers was the control group, who read stories that had nothing to do with either personal benefit or purpose. After the reading exercise, the workers hit the phones, admonished not to mention the stories they’d just read to the people they were trying to persuade to donate money.

A few weeks later, Grant looked at their sales numbers. The “personal benefit” and control groups secured about the same number of pledges and raised about the same amount of money as they had in the period before the story-reading exercise. But the people in the purpose group kicked into overdrive. They more than doubled “the number of weekly pledges that they earned and the amount of weekly donation money that they raised.”

19

Sales trainers, take note. This five-minute reading exercise more than

doubled

production. The stories made the work personal; their contents made it purposeful. This is what it means to serve: improving another’s life and, in turn, improving the world. That’s the lifeblood of service and the final secret to moving others.

—

I

n 1970, an obscure sixty-six-year-old former mid-level AT&T executive named Robert Greenleaf wrote an essay that launched a movement. He titled it “Servant as Leader”—and in a few dozen earnest pages, he turned the reigning philosophies of business and political leadership upside down. Greenleaf argued that the most effective leaders weren’t heroic, take-charge commanders but instead were quieter, humbler types whose animating purpose was to serve those nominally beneath them. Greenleaf called his notion “servant leadership” and explained that the order of those two words held the key to its meaning. “The servant-leader is servant first,” he wrote. “Becoming a servant-leader begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. Then conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead.”

20