This Great Struggle (55 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

Blair brought the letter to Lincoln. The president dismissed the absurd notion of the Mexican gambit but, eager to try any realistic possibility of ending the bloodshed sooner, thought the idea of a peace conference sounded interesting. He gave Blair a letter, dated January 18, expressing his willingness to meet with whatever commissioners Davis might appoint “with the view of securing peace to the people of our one common country.” Three days later Blair was in Richmond meeting with Davis. The Confederate president did not like Lincoln’s reference to “one common country” and seized on an off-hand suggestion of Blair’s about settling the war through a military conference between Grant and Lee. Maybe Grant could be persuaded in the name of soldierly camaraderie to give up essential Union war aims. Lincoln quickly extinguished even that forlorn hope by immediately nixing the idea of any such military conference.

That left Davis nothing but to appoint peace commissioners. He shrewdly chose Stephens to lead the mission since it would almost inevitably demonstrate the hollowness of the claims of the Confederate peace movement that peace could be had without reunion. Having the most visible leader of the peace movement heading the delegation would discredit the peace movement that much more. To accompany Stephens, Davis chose Confederate secretary of war (and former associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court) John A. Campbell and president pro tem of the Confederate senate, Robert M. T. Hunter. Davis, on January 28, 1865, gave them a written commission to meet with Lincoln “for the purpose of securing peace to the two countries.”

That wording nearly got them turned back when they tried to pass through Union lines under a flag of truce, but Grant intervened to let them through anyway. They met with Lincoln and Secretary of State William H. Seward on February 3 on board the steamboat

River Queen

on the body of water called Hampton Roads at the mouth of the James River. The meeting opened with pleasantries about Lincoln’s and Stephens’s former associations in the old Whig Party, but when it turned to business the predictable impasse arose immediately as Lincoln explained that peace was possible only with reunion. Stephens brought up the Mexican business, but Lincoln dismissed it. Campbell asked what terms the southern states could expect in case of reunion at that time, and Lincoln replied that he would be as lenient as possible and would urge Congress to provide compensation to the former slaveholders for their lost human chattels.

Asked about such things as the continued existence of West Virginia or the ongoing validity of the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln replied that the courts would decide such things. This he could do since he had recently replaced the late Chief Justice Roger B. Taney with the old-line abolitionist Salmon P. Chase. He advised Stephens to go home and take Georgia out of the Union and then have it ratify the recently introduced Thirteenth Amendment, which would end slavery throughout the United States. The Confederate vice president would do nothing of the sort. Carp as Stephens might against the Davis administration, he lacked nerve for so bold a step. After four hours the conference ended, and the members took their leave of one another.

When the Confederate commissioners returned to Richmond, Davis skillfully exploited the outcome of the Hampton Roads Conference as proof that Lincoln would grant them no peace without their “submission,” a term unspeakably odious to a ruling class comprised of slaveholders. Davis invoked the verbal imagery of slavery in an opposite sense in a fiery and impassioned speech at a mass meeting attended by an estimated ten thousand citizens in Richmond a few days later. The Confederacy would, Davis promised, “teach the insolent enemy who had treated our proposition with contumely in that conference in which he had so plumed himself with arrogance, [that] he [Lincoln] was, indeed talking to his masters.” Even Davis’s political enemies within the Confederacy had to confess that it had been “the most remarkable speech of his life,” and Stephens, attending the meeting despite his despair, called the speech “brilliant,” though he thought Davis “demented.” Nothing more was heard from the Confederate peace movement. Confederate morale rose as reports of the conference and of Davis’s remarks were read throughout the South. Even recently ravaged Georgia experienced a revival of fighting spirit, as southern whites rallied behind their president to follow the dream of a slaveholders’ republic to its conclusion in blood and fire.

2

13

“LET US STRIVE ON TO FINISH THE WORK”

SHERMAN’S CAROLINAS CAMPAIGN

M

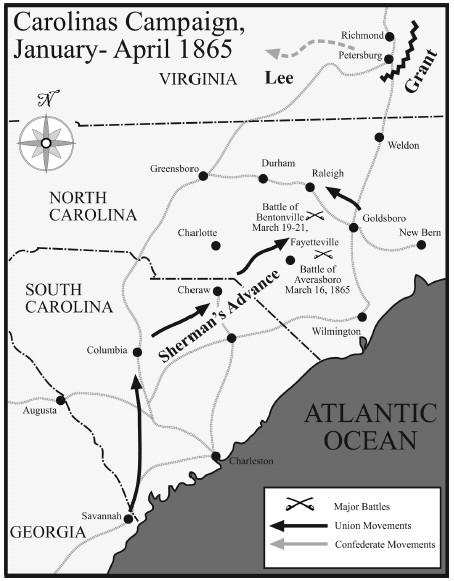

eanwhile, 450 miles to the south of Richmond in Savannah, Georgia, Sherman had been contemplating his next move and corresponding with Grant about the possibilities. Grant initially wanted Sherman to leave an adequate garrison in Savannah and ship the rest of his force by sea to join Grant in Virginia, but Sherman pointed out that it would take months to assemble the necessary shipping to transport his sixty thousand men to Virginia. As an alternative, he proposed to march his force north more than four hundred miles through the Carolinas and southern Virginia to join Grant outside Petersburg. Along the way his troops would wreak the sort of infrastructure damage they had done in Georgia and demoralize the civilian population. Grant gave his approval.

Sherman’s troops were more than ready for such an operation. Their letters and diaries were virtually unanimous in expressing their longing to visit South Carolina. There secession had been born, and because of secession these men had spent the past three or four years living the hard life of soldiers and seeing many of their comrades killed or maimed. Many wrote during the weeks in Savannah of the debt they owed the Palmetto State and were eager to repay. The soldiers had been on their best behavior in Savannah, but Sherman knew it would be different once they crossed into South Carolina. “I almost tremble for [South Carolina],” he wrote, “but feel she deserves all that seems in store for her.”

On February 1, two days before Lincoln and Seward met with the Confederate commissioners at Hampton Roads, Sherman’s troops began their advance. As in Georgia they marched in two separate wings. The right was the Army of the Tennessee under Howard, comprised of the Fifteenth and Seventeenth corps. The left, newly named the Army of Georgia, was commanded by Henry W. Slocum and composed of the Fourteenth and Twentieth corps. This was to be a much different campaign than the previous one however. The March to the Sea had occurred in a season when good weather was to be expected and had enjoyed mostly good weather. The Carolinas Campaign would be carried out in the rainiest season of the year and would lead right through the low-country swamps. Whereas the campaign in Georgia had generally paralleled the major streams, that in the Carolinas would run perpendicular to all the rivers in those states. The troops would lay scores of miles of corduroy road to accommodate their wagons and would wade hip deep in cold water for miles at a time crossing the flooded swamps.

The Carolinas Campaign also differed from the March to the Sea in that regular Confederate troops attempted to oppose Sherman’s march through the Carolinas. On February 3 a Confederate division of 1,200 men took advantage of overwhelming terrain advantages in trying to stop the Seventeenth Corps from crossing the Salkehatchie Swamp. Two brigades of Federals waded the swamp, sometimes under Confederate fire, and then outflanked the Rebels, forcing them to retreat. The same pattern was repeated again and again as Sherman’s supremely confident veterans overcame natural barriers and steadily increasing numbers of Confederates with seeming ease. Joseph Johnston later wrote that when he heard of the progress of Sherman’s men through the South Carolina swamps in winter, driving Confederate defenders before them, he became convinced that “there had been no such army since the days of Julius Caesar.”

As anticipated, the soldiers destroyed much property in South Carolina. Besides feeding themselves and their draft animals on the produce of the land and also constantly renewing their stock of draft animals at the expense of the farms they passed, they burned many more houses than they had in Georgia. An occupied house was usually safe, but most South Carolinians had fled, leaving their houses empty and thus consigning them to the flames. Even in South Carolina the soldiers did not kill, rape, or otherwise abuse civilians. Day by day Union foraging parties ranged for miles on either side of the army, gathering food supplies and skirmishing with Confederate troops as necessary. Foragers sometimes took over abandoned grist mills and ran them for a day or two, grinding foraged grain until the main column caught up with them. Then they turned over their stock of flour and ranged out ahead again.

Falling back ahead of the steadily advancing Federals were Confederate units released from coastal duty or detached from various other commands. The remnants of the Army of Tennessee were soon on their way to the Carolinas to confront once again their old foes in the western Union armies, now advancing up the eastern seaboard. Commanding the Confederate cavalry opposing Sherman was South Carolina planter grandee Wade Hampton, detached from Lee’s army, where he had led the cavalry after Stuart’s demise.

Hampton was determined that no South Carolina cotton should fall into the hands of Sherman’s Yankees and gave orders for his troopers to set fire to all stocks of cotton in advance of the Union troops. This sometimes created odd situations. When the Federals marched into the town of Orange, South Carolina, they found its business district already in flames, which had spread from the cotton warehouses Hampton’s men had torched. The bluecoats pitched in and helped the townsmen put out the fires. Then they removed the remaining unburned cotton bales from the warehouses, hauled them out a safe distance into the fields, and burned them. Sherman’s men were traveling light and could not transport the bulky, heavy cotton bales. They invariably burned any that Hampton’s men missed.

But Hampton’s men were engaging in another practice far less innocuous. Sherman’s men began to come upon the remains of foraging parties that had been surrounded by superior forces, captured, and then murdered. Some had their throats cut. Others were hanged. Many had crudely lettered signs placed on or with them with statements such as “Death to Foragers.” Foraging was well within the laws and customs of war. Murdering prisoners was not, and Sherman sent a letter to Hampton protesting the murders and asking if they were officially authorized. Hampton responded with a letter of his own, admitting that murdering prisoners was now his official policy and defending it as within his rights. The only way to stop such behavior was to retaliate, so Sherman ordered that henceforth a Confederate prisoner in his army’s possession face a firing squad for each forager found murdered. The Federals carried out that grim step precisely once. The Rebel prisoner who drew the short straw was a middle-aged man, the father of several children, and had recently been conscripted. Thereafter no further retaliation took place, and Hampton’s men went on murdering captured Federals literally up until the final days of the war.

On February 17 Sherman’s troops marched into Columbia, the capital of South Carolina, past smoldering piles of half-burned cotton that Hampton’s troopers had at least dragged into the streets before torching. That night high winds rose and fanned the heaps into flame, which spread to nearby buildings. Some of the Union soldiers had become drunk on liquor they found in the city and were determined to burn Columbia, as were some of their entirely sober comrades. Nor were they the only ones bent on conflagration that night. By many accounts, recently freed slaves as well as escaped prisoners from another of the infamous Confederate prison pens that had, until a few days before, been just outside of town, also engaged in setting fires, which sprang up at dozens of locations around the city.

Thousands of Union soldiers participated in the battle to fight the fires that night, both in units assigned to the task and as volunteers who hurried in from their camps outside of town. Meanwhile, some of their comrades with opposite intentions cut fire hoses and otherwise hindered the efforts to fight the fires. When the wind finally shifted and the fires went out, about one-third of Columbia, chiefly the business district, was in ashes or smoldering ruins. Among the relatively small number of residences to burn was Wade Hampton’s palatial mansion, one of several he owned. First Baptist Church, scene of the convention that had declared South Carolina’s secession almost four years before, escaped the flames. According to legend, the church’s groundskeeper misdirected vengeance-minded Union soldiers to a nearby Methodist church instead.

Over the days that followed, the Federals methodically destroyed everything of military value in Charleston and then, on February 20, having left adequate food supplies for the population, marched north. As Sherman’s soldiers marched away from the still-smoldering ruins of downtown Columbia, many soldiers speculated as to who or what had started the fire, but few if any would lose sleep over it. Whether they had fought the flames or lit them, Sherman’s soldiers were unanimous in their belief that the fire had been a just retribution for South Carolina’s sins.