This Great Struggle (26 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

British leaders received news of the Confederate victories in Virginia that summer with delight. In the wake of Second Bull Run, Foreign Secretary Lord John Russell suggested to Prime Minister Lord Palmerston that the time had come for Britain to recognize the Confederacy and perhaps propose mediation with a view to restoring peace on the basis of Confederate independence. Palmerston was more cautious. He had heard that Lee was north of the Potomac, which if true was sure to bring a showdown battle. He told Russell they should await the outcome of that battle before acting.

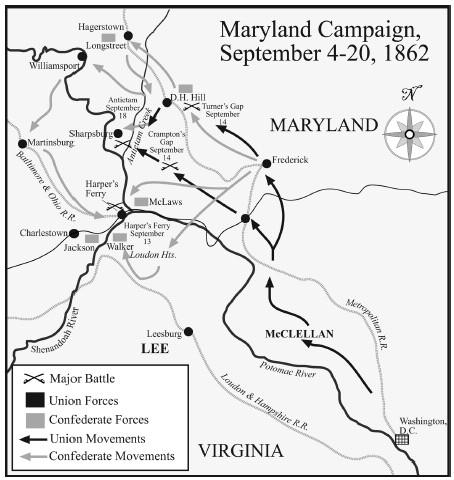

Lee had indeed crossed the Potomac. After failing to trap Pope at Chantilly, Lee had decided to keep the momentum of his campaign going by swinging to the west of Washington and crossing into Maryland, with a view to possibly proceeding deep into Pennsylvania. He wrote to Davis, informing him of his plans and stating that he planned to cross the Potomac the next day unless contrary orders arrived from the Confederate president. Those would have had to have been already on the way since Lee’s dispatch could not even have reached Davis before the first units of the Army of Northern Virginia began fording the Potomac near Leesburg on September 3.

By crossing the river east of the Blue Ridge and its northern extension, known somewhat perversely as South Mountain, Lee planned to keep up his threat to Washington, thus pinning Union troops down in its defenses. He then planned to march northwest and take control of the passes across South Mountain. These could be easily defended while his army cut off Washington’s communication with the West via the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and plundered the agricultural wealth of western Maryland and south-central Pennsylvania, living off the land and carrying away what it did not eat of the late-summer harvest. Also, Confederates had claimed since the beginning of the war that Maryland would eagerly join the Confederacy if not suppressed by Union troops. Some Marylanders certainly encouraged that view. A number of Maryland men had enlisted in the Confederate army, and some Maryland women had come south as refugees from Union rule, notably the beautiful and prominent Cary sisters of Baltimore, Jenny, Hetty, and their cousin Constance, who had sewn the first Confederate battle flag.

The Cary sisters also found a tune, “O Tannenbaum,” to which James Ryder Randall’s 1861 poem “Maryland, My Maryland” could be sung. Written in the wake of the Baltimore riot by a Marylander living in Louisiana, the poem called on citizens of the state to rise up and join the Confederacy:

The despot’s heel is on thy shore,

Maryland! My Maryland!

His torch is at thy temple door,

Maryland! My Maryland!

Avenge the patriotic gore

That flecked the streets of Baltimore,

And be the battle queen of yore,

Maryland! My Maryland!

With eight more stanzas in similar vein, the song immediately became a favorite all across the South, played by brass bands or sung by many a young woman, accompanying herself on the piano, for the benefit of nattily uniformed young men about to depart for the seat of war. Various bands in Lee’s army played it as their units splashed through the shallow waters of the Potomac or marched northward into the Old Line State. This would be Maryland’s chance to cast its lot with the Confederacy.

Lee believed he could remain in Maryland or in Pennsylvania for an extended period with impunity because he reckoned that the Union army around Washington was completely demoralized and would not be ready for battle again for weeks if not months. If as reported McClellan was back in command of that army, so much the better. Lee had taken McClellan’s measure on the peninsula and believed he had little to fear from the Young Napoleon and certainly not anytime soon.

Lee hoped that his present campaign might be the last of the war. The Confederacy was riding high after his recent victories, and even in the West, Confederate armies had gone over to the offensive in Tennessee and Mississippi. Lee sent a dispatch to Jefferson Davis suggesting that with a Confederate army on northern soil, this would be a good time to call on Lincoln to give up the war and grant Confederate independence. Davis thought more like Palmerston, reckoning that a Confederate army north of the Potomac guaranteed an impending showdown battle whose results both Lincoln and the British would await before deciding their next move. To Lee’s dismay, however, Davis decided that the prospect of a battle leading to a political settlement required his personal presence with the army and wrote Lee to say he was coming. Lee did not want the president looking over his shoulder and in a series of courteous but insistent dispatches succeeded in persuading Davis that it would not be wise for him to hazard himself on the road between Richmond and the army at this time.

The first disappointment for the Confederates was the chilly greeting they received from the people of Maryland. Western Maryland, in which the Army of Northern Virginia was now campaigning, was a land of relatively few slaves and overwhelming allegiance to the Union. Only a few Marylanders hailed the Rebels’ coming. If Lee’s army was disappointed in the Marylanders, the feeling was mutual. Its ranks much diminished by battle losses, as well as straggling by men exhausted or suffering from combat fatigue, numbered only about thirty-eight thousand. After more than a year in an army whose quartermaster department did at best an indifferent job of supplying new uniforms and accoutrements and after a summer of intense campaigning, the Confederate soldiers presented a ragged appearance, and one Maryland diarist recorded that they were the dirtiest group of men she had ever seen. The Marylanders had to admit, though, that Lee’s men had a certain swagger about them.

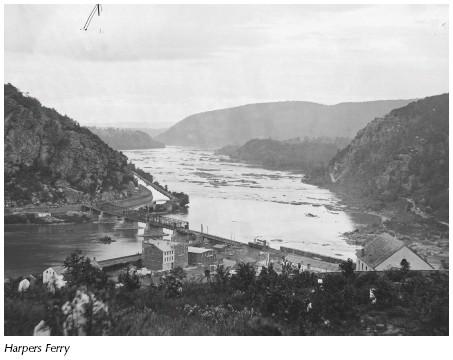

A glitch arose in Lee’s plan when the ten-thousand-man Union garrison of Harpers Ferry declined to evacuate when Lee’s army passed north of it. Located where the Shenandoah River flows into the Potomac and then the Potomac passes through a narrow gap between the Blue Ridge and South Mountain, Harpers Ferry lies in a basin surrounded by high ground. No one could hold Harpers Ferry without holding that high ground. Lee’s thirty-eight thousand men could fairly easily push the ten thousand Federals off the heights, trapping them in the basin of Harpers Ferry and compelling their surrender. That is why Lee had expected the Federals to pull out once he got well north of the Potomac. When they called his bluff and stayed put, Lee faced a difficult choice. To take the necessary high ground around Harpers Ferry, he would have to divide his army into at least three columns and send them marching by widely separated routes to come at Harpers Ferry from multiple directions. If McClellan moved aggressively toward him, Lee would be in a very dangerous situation with the components of his army so widely separated that they could not support each other and thus would be easy prey for the Army of the Potomac. Yet Lee could not afford to leave the Harpers Ferry garrison where it was since its presence in the lower Shenandoah Valley would interfere with his plans to have wagons haul at least some of his supplies from the valley via the excellent macadamized Valley Pike.

Lee believed he could trust McClellan not to be aggressive, and so on September 9, with his army encamped in and around Frederick, Maryland, Lee drafted Special Order Number 191, giving detailed instructions to his subordinates as to how the army should divide into four columns, three to march on Harpers Ferry by different routes and one to cover their rear against harassing Union cavalry from the direction of Washington by holding the passes of South Mountain. During the days that followed all went well for the Army of Northern Virginia as its separated components implemented Lee’s plan. McClellan, who was under considerable pressure from Lincoln to do something about the Rebels north of the Potomac, advanced with uncharacteristic speed though still slow enough to give Lee plenty of time to carry out his plans. Thus, Lee’s army marched northwest toward Harpers Ferry, and McClellan’s, advancing from Washington, followed behind.

On the morning of September 13, some of McClellan’s troops were resting in a field outside Frederick when two Indiana soldiers found three cigars lying on the ground, wrapped with a paper that, on further examination, looked important. History does not tell us what happened to the cigars, but the paper, which was a copy of Lee’s Special Order Number 191, was quickly passed up the chain of command to McClellan himself, who read it and exclaimed, “Now I know what to do! Here is a paper with which, if I cannot whip Bobby Lee, I will be ready to go home.” To Lincoln he telegraphed, “No time shall be lost. I think Lee has made a gross mistake, and that he will be severely punished for it. I have all the plans of the rebels, and will catch them in their own trap if my men are equal to the emergency.”

Special Order Number 191 told McClellan that Lee’s army was scattered and vulnerable and furthermore told him exactly where he could find its isolated parts. Since the order was already several days old, time was of the essence. A competent general would have put his army in motion at once. McClellan ordered the Army of the Potomac to wait eighteen hours and march the following morning, September 14.

Lee was stunned when scouts informed him that the Army of the Potomac was advancing aggressively toward the detachments he had left to hold three key gaps in South Mountain. Shortly thereafter he learned the reason why. A pro-Confederate civilian had actually been inside McClellan’s headquarters when Special Order Number 191 arrived and brought word to Lee of the intelligence disaster. A quick investigation revealed the source of the leak. D. H. Hill’s division had been operating with Jackson’s command but still technically answered to Lee’s headquarters. Both headquarters had copied the order to Hill, each not realizing what the other had done. Hill received only one of the copies, but when he confirmed that he had it, each headquarters assumed that all copies of the order were accounted for. The extra copy had somehow ended up wrapped around the cigars in the field outside Frederick.

Lee moved to salvage the situation, positioning his available troops to hold the passes of South Mountain. Most of his army had recently taken up its positions surrounding Harpers Ferry, and the only way they could quickly reunite would be through Harpers Ferry. If the Federal outpost held out several more days and if McClellan acted intelligently on the information he now had, Lee’s situation would be dire.

THE BATTLE OF ANTIETAM

Prospects for the Army of Northern Virginia looked very grim indeed as Federal troops approached South Mountain that afternoon and, after several hours of cautious preparations, moved to assault the outnumbered Confederates. The heaviest fighting took place at Turner’s Gap, northernmost of the three, where the National Road passed over the mountain and Lee had most of his troops. Watching Gibbon’s Black Hat Brigade drive the defenders back toward the gap, McClellan is supposed to have exclaimed that the brigade was made of iron, giving it a new nickname, the Iron Brigade. Fighting continued at Turner’s Gap for several hours, and the Confederates were just on the point of losing their last grip on the gap as darkness fell.

A few miles to the south, other Confederate forces successfully held Fox’s Gap, but a few miles beyond that lay Crampton’s Gap, where Confederate numbers had sufficed to provide only a few hundred defenders. McClellan proteégeé William B. Franklin, commanding the Sixth Corps, delayed for hours before launching an attack with overwhelming numbers that cleared the gap. With that, Franklin was in position to begin the destruction of Lee’s army since he could have advanced toward Harpers Ferry, scarcely ten miles away, and made the fragmentation of Lee’s army complete and irrevocable. Franklin was a true disciple of his mentor McClellan, however, and so, concluding that he was vastly outnumbered when in fact the exact opposite was the case, he halted and took up a defensive position.