This Great Struggle (57 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

Down in North Carolina, Johnston on March 19 launched his first major offensive operation since the Battle of Fair Oaks, just outside Richmond almost three years before. With Sherman’s forces advancing on a broad front that almost invited attack, Johnston took the bait and struck at Slocum’s army near Bentonville, North Carolina. The Confederates scored some limited initial success, but then Sherman’s veterans rallied and held their own. Howard’s Army of the Tennessee moved in to support its comrades in Slocum’s army, and had Johnston lingered a little longer before retreating or had Sherman possessed a bit more of the killer instinct, the Confederate army in North Carolina might have reached its demise there and then. As it was, in the three days of sporadic fighting, Johnston’s army suffered more than 2,600 casualties to scarcely more than 1,500 Union losses.

Back up in Virginia Lee planned to attack a Union bastion named Fort Stedman, located along Grant’s lines just east of Petersburg. If the attack was successful, Grant might have to pull back his left wing, which now extended ten miles to the southwest of Petersburg, in order to shore up his broken lines east of town. That would give Lee the opportunity to take his army and slip around the Union left to head for North Carolina and the hoped-for rendezvous with Johnston.

Lee entrusted the job to Major General John B. Gordon, now commanding the Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia. Gordon planned the operation meticulously, and the Confederates launched their assault in the predawn darkness at 4:15 a.m., March 25. Initially they had things all their own way, surprising the defenders and overrunning Fort Stedman and several smaller neighboring works. Then the attack bogged down in the disorganization that always followed the storming of defenses. Union artillery took the captured fort under heavy fire, and then a Union counterattack swept back over the captured positions, sending the surviving Confederate attackers fleeing back across no-man’s-land under deadly fire of rifles and artillery.

It was over by 8:00 that morning. Union casualties totaled about one thousand, Confederate about four times that many. Union reserves in that sector had easily repulsed the brief penetration, and Grant had had no need to shift any troops from other sectors. Lincoln arrived at Grant’s headquarters later that morning and mentioned the Battle of Fort Stedman in a cable he sent to Secretary of War Stanton informing him of his safe arrival: “There was a little rumpus up the line this morning, ending about where it began.” Such was the impact the Army of Northern Virginia made in its last great offensive.

Grant had been planning an offensive of his own, to be led by Sheridan and aimed once again at the right flank of the Confederate position around Petersburg, aiming as always toward cutting the rail lines southwest of Petersburg. Along with his cavalry, Sherman would also have the Fifth Corps. His troops moved out on March 29, swinging well to the southwest, beyond the ends of both side’s entrenchments. They clashed that first day with Confederate forces patrolling the roads and drove the Rebels back. The next day, however, saw heavy rain that turned the roads to quagmires, slowing the march. While Sheridan’s men slogged through the mud, Lee recognized the threat and shifted George Pickett’s division of infantry from the other end of the line out to a position to counter Sheridan. He also reinforced Pickett with the cavalry division of Major General W. H. F. Lee, the son of Robert E. Lee.

On the last day of March, Pickett’s command met Sheridan’s advance near Dinwiddie Court House. Though he suffered twice as many casualties as the Federals, Pickett managed to halt Sheridan’s advance and even drive the blue-jacketed troopers back a short distance. Union mistakes and unfamiliarity with the lay of the land and the location of the Confederate positions were helpful to Pickett in that day’s fighting. That night Pickett learned that a large formation of Union infantry (the Fifth Corps) was moving up from the east in support of Sheridan’s cavalry. Fearing that he would be flanked, Pickett ordered his men to fall back from their position northwest of Dinwiddie Court House.

Learning of Pickett’s withdrawal, Lee (the father) was displeased. Dinwiddie lay only about eight miles from the vital Southside Railroad, and Pickett’s force was all Lee could spare for the vital task of keeping Sheridan away from the tracks. Though Pickett had planned to fall back to a position behind Hatcher’s Run, scarcely a mile and a half from the railroad, Lee recognized that if Sheridan gained control of the key road junction known as Five Forks, three miles from the Southside, he would be in a position from which it would be almost impossible to prevent him from breaking the railroad. Lee therefore sent Pickett orders to entrench in front of the key intersection and “hold Five Forks at all hazards.”

Pickett obeyed, and his men spent the morning of All Fools’ Day digging in just south of the crossroads. By the middle of the day, Pickett felt confident enough in the strength of his position and doubtful enough as to whether Sherman would persevere in the operation after the check he had received the day before to accept an invitation from several of his fellow officers to attend a shad bake two miles to the rear. When he went, he neglected to inform subordinates of his absence, leaving his command effectively leaderless. While Pickett and his hosts enjoyed their meal of fish, Sheridan, having finally overcome the difficult terrain, struck hard at the position around Five Forks. As the Confederate lines crumbled, Pickett failed to hear the roar of battle, apparently because of unfavorable atmospheric conditions. By the time he returned to his command, it was reeling back in headlong retreat, and Sheridan held Five Forks.

Notified later that evening of the results of the fighting around Five Forks, Grant immediately recognized its significance. He ordered every cannon and mortar along the whole length of his lines to open fire on the Confederate positions and keep firing all through the night. At dawn Grant’s infantry surged forward in a mass assault all along the front. The badly thinned Confederate lines broke in multiple places. Hurrying to a breach in his own sector, Confederate corps commander A. P. Hill encountered the advancing Union troops, who shot him dead. Elsewhere Confederate defenders clung tenaciously to several key forts, delaying the Union advance.

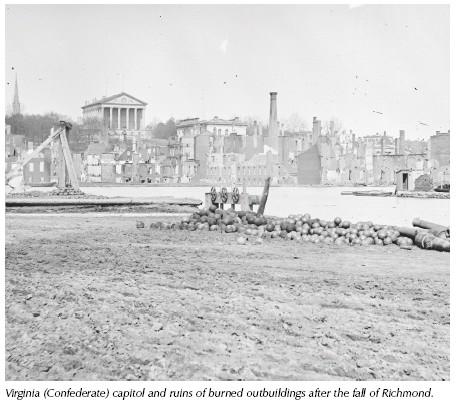

Desperately struggling to extricate his army from the collapsing position around Petersburg and Richmond, Lee hastily wrote to Davis notifying him that the two cities would fall that day and that if the Confederate government wanted to get out, the time had come. Davis was attending services at St. Paul Episcopal Church in Richmond when the sexton quietly handed him the note from Lee. Davis silently read it, then rose and left, leaving the other congregants to guess its meaning. He supervised the hasty packing up of remaining government files, and then he and most of his cabinet boarded one of the last trains out of the city, hoping to reestablish the seat of government in Lynchburg, Virginia, a little more than one hundred miles to the west of Richmond. Back in the former Confederate capital, panic reigned and looting raged among the civilian populace as the Confederate rear guard set fire to military installations and depots to prevent their falling into Union hands. The flames spread and destroyed much of the city.

THE ROAD TO APPOMATTOX COURT HOUSE

Lee succeeded in getting most of his troops out of the doomed enclave around Richmond and Petersburg and marched west, hoping to get clear of Grant’s pursuit and turn southwest and then south to link up with Johnston’s army. Lee’s army, though much depleted, was in high spirits at being out of the entrenchments and back on open roads in unspoiled countryside, the sort of environment in which the army had won its great victories under Lee two years before. If anyone in the gray-clad ranks thought the army’s demise was near, he generally kept quiet about it.

Grant was determined to make it happen. Thus far in the war no major army had been chased down after a defeat, trapped, and forced to surrender— unless one counted Pemberton’s army, which had taken refuge in Vicksburg after its defeat at Champion Hill. Lee was no Pemberton and would not hole up in a fortress for Grant to besiege. Grant would have to catch him, and he set out to do so. He ordered his troops to follow Lee immediately. Only those that had been on the east side of Richmond actually got to pass through the newly captured city. The Army of the Potomac, which had striven to take Richmond since its days under McClellan three years before, bypassed the city, marching west in hot pursuit of its old nemesis the Army of Northern Virginia. While Meade and his army followed close at Lee’s heels, Sheridan with his cavalry as well as Major General E. O. C. Ord, commanding the Army of the James in place of the finally discredited Butler, strove to pass Lee’s flanks and block his escape.

While the armies marched rapidly west, Lincoln on April 4 arrived in Richmond by boat on the James River. The city had been in Union hands less than twenty-four hours and was lightly occupied. Accompanied only by his son Tad, whose twelfth birthday this was, Lincoln went ashore at the landing and walked through the town. Alarmed at this appalling lapse of security, Porter hastily gathered a squad of armed sailors and set out after the president. While Richmond’s whites glowered resentfully or peered at him through nearly shut window blinds, the black population flocked into the streets to greet and celebrate the man they considered their deliverer from bondage. Before leaving town, Lincoln visited the Confederate White House and sat pensively in a chair Jefferson Davis had occupied not two days earlier.

That same day, April 4, Lee’s army reached Amelia Court House, on the Richmond & Danville Railroad about forty miles west-northwest of Petersburg and the same distance west-southwest of Richmond. There the elements of Lee’s army that had been in the trenches around Petersburg joined those that had been holding the lines east of Richmond. More important, however, was what had not arrived at Amelia Court House. During the evacuation of the lines, Lee had given orders for the commissary department to load supplies from the Richmond depots onto several trains and ship them out the Richmond & Danville to Amelia Court House so that the army would find them waiting when it arrived. Somehow in the confusion of that last day in Richmond, the ammunition had moved out as ordered, but the much more desperately needed rations had gone astray. Now Lee found himself with nothing to feed his hungry army. Reluctantly he gave orders for the army to spend the next twenty-four hours at Amelia while foraging parties fanned out in the vicinity to seize food. They found little enough, and by the time the army marched on again, it had lost what little lead it had over Grant’s pursuing columns.

The Confederates had gone little more than seven miles on their resumed march when they found Sheridan’s cavalry blocking the southwest fork of the road at Jetersville. With Union infantry bearing down on the rear of his army, Lee could not afford to slow his pace in order to push the cavalry out of the way. That left no option but to continue to the west, not toward Danville now, as originally planned, but toward Lynchburg. The immediate goal was Farmville, where the commissary department gave Lee to understand he could expect to meet another shipment of rations. So the Army of Northern Virginia slogged wearily onward, no longer maneuvering toward Johnston and the forlorn hope of a combination against Sherman but simply fleeing like a deer half a step ahead of the pursuing wolf pack.

The next day, April 6, Lee’s army marched by two roads, as armies always did when quick marching was necessary and parallel roads were available. Longstreet’s large corps took the southerly road while the smaller corps of Ewell and of Richard H. Anderson took the northerly. Union infantry pressed close after the rear of the columns while Union cavalry, supported by more infantry, harassed both flanks. At Rice’s Station, twelve miles beyond Jetersville, Longstreet again found Union troops, this time Ord’s Army of the James, firmly blocking any possible turn to the south toward North Carolina and Johnston’s army.

While Longstreet was busy skirmishing near Rice’s Station, Union infantry pressed so close to the rear of Ewell’s column that he had to turn at bay to hold them back. This caused the northerly of Lee’s two columns to stretch thin, as Anderson’s corps did not immediately halt. Sheridan, commanding the Union cavalry on that flank, saw the opportunity and sent two of his divisions in headlong attack. They ripped through Anderson’s column, turned, and came crashing down on Ewell’s flank and rear as his troops were fighting against Union infantry along the valley of Sayler’s Creek. Trapped, Ewell’s men surrendered in droves, and presently Ewell himself surrendered as well. In all, nearly three thousand Confederates were killed or wounded at Sayler’s Creek, and another six thousand were captured. Union losses totaled a little more than one thousand. Lee personally rallied the fleeing remnants of Anderson’s corps and borrowed troops from Longstreet to help stabilize the situation, but the debacle had cost his already badly depleted army almost a third of its strength.

“If the thing is pressed,” Sheridan wrote Grant that day, “I think that Lee will surrender.” A copy of the dispatch made its way back to Grant’s supply base at City Point, east of Petersburg, where Lincoln was anxiously awaiting news of the campaign. On April 7 the president fired off a dispatch of his own to Grant, noting Sheridan’s message and adding, “Let the

thing

be pressed.” Grant had every intention of doing just that. He was already conducting the most aggressive pursuit by any major army in the war, and he was not about to let up. That same day he had sent Lee a message by a flag of truce: “The result of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia in this struggle. I feel that is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood, by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the C.S. Army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.” While he waited for a reply, he kept his troops in rapid pursuit of Lee’s dwindling force.