The World Was Going Our Way (85 page)

Read The World Was Going Our Way Online

Authors: Christopher Andrew

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #True Accounts, #Espionage, #History, #Europe, #Ireland, #Military, #Intelligence & Espionage, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #20th Century, #Russia, #World

Ridiculed and reviled at the end of the Soviet era, the Russian intelligence community has since been remarkably successful at re-inventing itself and recovering its political influence. The last three prime ministers of the Russian Federation during Boris Yeltsin’s presidency - Yevgeni Primakov, Sergei Stepashin and Vladimir Putin - were all former intelligence chiefs. Putin, who succeeded Yeltsin as President in 2000, is the only FCD officer ever to become Russian leader.

57

According to the head of the SVR, Sergei Nikolayevich Lebedev, ‘The president’s understanding of intelligence activity and the opportunity to speak the same language to him makes our work considerably easier.’

58

No previous head of state in Russia, or perhaps anywhere else in the world, has ever surrounded himself with so many former intelligence officers.

59

Putin also has more direct control of intelligence than any Russian leader since Stalin. According to Kirpichenko, ‘We are under the control of the President and his administration, because intelligence is directly subordinated to the President and only the President.’ But whereas Stalin’s intelligence chiefs usually told him simply what he wanted to hear, Kirpichenko claims that, ‘Now, we tell it like it is.’

60

57

According to the head of the SVR, Sergei Nikolayevich Lebedev, ‘The president’s understanding of intelligence activity and the opportunity to speak the same language to him makes our work considerably easier.’

58

No previous head of state in Russia, or perhaps anywhere else in the world, has ever surrounded himself with so many former intelligence officers.

59

Putin also has more direct control of intelligence than any Russian leader since Stalin. According to Kirpichenko, ‘We are under the control of the President and his administration, because intelligence is directly subordinated to the President and only the President.’ But whereas Stalin’s intelligence chiefs usually told him simply what he wanted to hear, Kirpichenko claims that, ‘Now, we tell it like it is.’

60

The mission statement of today’s FSB and SVR is markedly different from that of the KGB. At the beginning of the 1980s Andropov proudly declared that the KGB was playing its part in the onward march of world revolution.

61

By contrast, the current ‘National Security Concept’ of the Russian Federation, adopted at the beginning of the new millennium, puts the emphasis instead on the defence of traditional Russian values:

61

By contrast, the current ‘National Security Concept’ of the Russian Federation, adopted at the beginning of the new millennium, puts the emphasis instead on the defence of traditional Russian values:

Guaranteeing the Russian Federation’s national security also includes defence of the cultural and spiritual-moral inheritance, historical traditions and norms of social life, preservation of the cultural property of all the peoples of Russia, formation of state policy in the sphere of the spiritual and moral education of the population . . .

One of the distinguishing characteristics of the Soviet intelligence system from Cheka to KGB was its militant atheism. In March 2002, however, the FSB at last found God. A restored Russian Orthodox church in central Moscow was consecrated by Patriarch Aleksi II as the FSB’s parish church in order to minister to the previously neglected spiritual needs of its staff. The FSB Director, Nikolai Patrushev, and the Patriarch celebrated the mystical marriage of the Orthodox Church and the state security apparatus by a solemn exchange of gifts. Patrushev presented a symbolic golden key of the church and an icon of St Aleksei, Moscow Metropolitan, to the Patriarch, who responded by giving the FSB Director the Mother of God ‘Umilenie’ icon and an icon representing Patrushev’s own patron saint, St Nikolai - the possession of which would formerly have been a sufficiently grave offence to cost any KGB officer his job. Though the FSB has not, of course, become the world’s first intelligence agency staffed only or mainly by Christian true believers, there have been a number of conversions to the Orthodox Church by Russian intelligence officers past and present - among them Nikolai Leonov, who half a century ago was the first to alert the Centre to the revolutionary potential of Fidel Castro. ‘Spirituality’ has become a common theme in FSB public relations materials. While head of FSB public relations in 1999-2001, Vasili Stavitsky published several volumes of poetry with a strong ‘spiritual’ content, among them

Secrets of the Soul

(1999); a book of ‘spiritual-patriotic’ poems for children entitled

Light a Candle, Mamma

(1999); and

Constellation of Love: Selected Verse

(2000). Many of Stavitsky’s poems have been set to music and recorded on CDs, which are reported to be popular at FSB functions.

62

Secrets of the Soul

(1999); a book of ‘spiritual-patriotic’ poems for children entitled

Light a Candle, Mamma

(1999); and

Constellation of Love: Selected Verse

(2000). Many of Stavitsky’s poems have been set to music and recorded on CDs, which are reported to be popular at FSB functions.

62

Despite their unprecedented emphasis on ‘spiritual security’, however, the FSB and SVR are politicized intelligence agencies which keep track of President Putin’s critics and opponents among the growing Russian diaspora abroad,

63

as well as in Russia itself. During his first term in office, while affirming his commitment to democracy and human rights, Putin gradually succeeded in marginalizing most opposition and winning control over television channels and the main news media. The vigorous public debate of policy issues during the Yeltsin years has largely disappeared. What has gradually emerged is a new system of social control in which those who step too far out of line face intimidation by the FSB and the courts. The 2003 State Department annual report on human rights warned that a series of alleged espionage cases involving scientists, journalists and environmentalists ‘caused continuing concerns regarding the lack of due process and the influence of the FSB in court cases’. According to Lyudmila Alekseyeva, the current head of the Moscow Helsinki Group, which has been campaigning for human rights in Russia since 1976, ‘The only thing these scientists, journalists and environmentalists are guilty of is talking to foreigners, which in the Soviet Union was an unpardonable offence.’

64

Though all this remains a far cry from the KGB’s obsession with even the most trivial forms of ideological subversion, the FSB has once again defined a role for itself as an instrument of social control.

63

as well as in Russia itself. During his first term in office, while affirming his commitment to democracy and human rights, Putin gradually succeeded in marginalizing most opposition and winning control over television channels and the main news media. The vigorous public debate of policy issues during the Yeltsin years has largely disappeared. What has gradually emerged is a new system of social control in which those who step too far out of line face intimidation by the FSB and the courts. The 2003 State Department annual report on human rights warned that a series of alleged espionage cases involving scientists, journalists and environmentalists ‘caused continuing concerns regarding the lack of due process and the influence of the FSB in court cases’. According to Lyudmila Alekseyeva, the current head of the Moscow Helsinki Group, which has been campaigning for human rights in Russia since 1976, ‘The only thing these scientists, journalists and environmentalists are guilty of is talking to foreigners, which in the Soviet Union was an unpardonable offence.’

64

Though all this remains a far cry from the KGB’s obsession with even the most trivial forms of ideological subversion, the FSB has once again defined a role for itself as an instrument of social control.

Russian espionage in the West appears to be back to Cold War levels.

65

In the post-Soviet era, however, the disappearance beyond the horizon of the threat of thermonuclear conflict between Russia and the West, the central preoccupation of intelligence agencies on both sides during the Cold War, means that Russian espionage no longer carries the threat which it once did. Early twenty-first-century intelligence has been transformed by the emergence of counter-terrorism as, for the first time, a greater priority than counterespionage. In the 1970s the KGB saw terrorism as a weapon which could, on occasion, be used against the West.

66

The FSB and SVR no longer do. While Russia and the West still spy on each other, they co-operate in counter-terrorism. Given the transnational nature of terrorist operations, they have no other rational option. The head of the SVR, S. N. Lebedev, declared a year after 9/11, ‘No country in the world, not even the United States with all its power, is now able to counter these threats on its own. Co-operation is essential.’

67

Today’s FSB and SVR have formal, if little-advertised, liaisons with Western intelligence agencies. In 2004 at the holiday resort of Sochi on the Black Sea the FSB hosted a meeting of intelligence chiefs from seventy foreign services (including senior representatives of most leading Western agencies) to discuss international collaboration in counter-terrorism. In the course of the conference, delegates watched an exercise (codenamed NABAT) by Russian special forces to free hostages from a hijacked plane at Sochi airport.

68

65

In the post-Soviet era, however, the disappearance beyond the horizon of the threat of thermonuclear conflict between Russia and the West, the central preoccupation of intelligence agencies on both sides during the Cold War, means that Russian espionage no longer carries the threat which it once did. Early twenty-first-century intelligence has been transformed by the emergence of counter-terrorism as, for the first time, a greater priority than counterespionage. In the 1970s the KGB saw terrorism as a weapon which could, on occasion, be used against the West.

66

The FSB and SVR no longer do. While Russia and the West still spy on each other, they co-operate in counter-terrorism. Given the transnational nature of terrorist operations, they have no other rational option. The head of the SVR, S. N. Lebedev, declared a year after 9/11, ‘No country in the world, not even the United States with all its power, is now able to counter these threats on its own. Co-operation is essential.’

67

Today’s FSB and SVR have formal, if little-advertised, liaisons with Western intelligence agencies. In 2004 at the holiday resort of Sochi on the Black Sea the FSB hosted a meeting of intelligence chiefs from seventy foreign services (including senior representatives of most leading Western agencies) to discuss international collaboration in counter-terrorism. In the course of the conference, delegates watched an exercise (codenamed NABAT) by Russian special forces to free hostages from a hijacked plane at Sochi airport.

68

Despite their public emphasis on ‘spiritual security’, both the FSB and SVR look back far less to a distant pre-revolutionary past than to their Soviet roots, holding an annual celebration on 20 December, the date of the founding of the Cheka six weeks after the Revolution as the ‘sword and shield’ of the Bolshevik regime. The FSB continues to campaign for the replacement of the statue of the Cheka’s founder, Feliks Dzerzhinsky, on the pedestal outside its headquarters from which it was removed after the failed coup of August 1991. The SVR dates its own foundation from 20 December 1920, when the Cheka’s foreign department was established. It celebrated its seventy-fifth anniversary in 1995 by publishing an uncritical eulogy of the ‘large number of glorious deeds’ performed by Soviet intelligence officers ‘who have made an outstanding contribution to guaranteeing the security of our Homeland’.

69

A multi-volume history, begun by Primakov as head of the SVR and still in progress, is similarly designed to show that, from the Cheka to the KGB, Soviet foreign intelligence ‘honourably and unselfishly did its patriotic duty to Motherland and people’.

70

Much as Russian intelligence has evolved since the collapse of the Soviet Union, it has yet to come to terms with its own past.

69

A multi-volume history, begun by Primakov as head of the SVR and still in progress, is similarly designed to show that, from the Cheka to the KGB, Soviet foreign intelligence ‘honourably and unselfishly did its patriotic duty to Motherland and people’.

70

Much as Russian intelligence has evolved since the collapse of the Soviet Union, it has yet to come to terms with its own past.

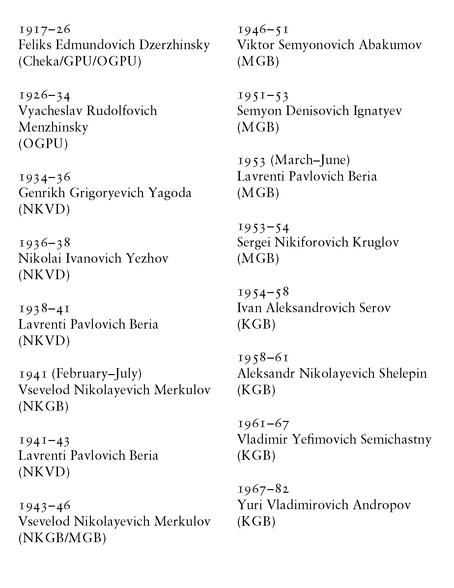

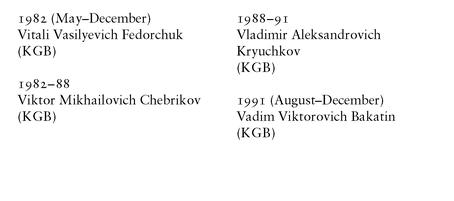

Appendix A

KGB Chairmen, 1917-91

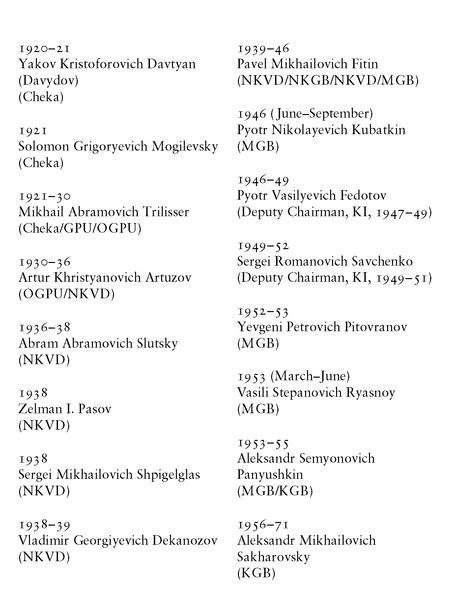

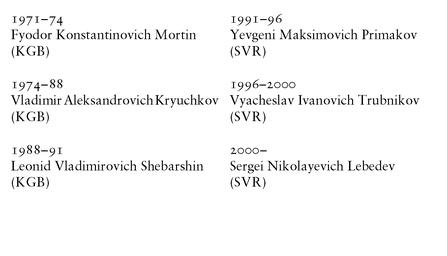

Appendix B

Heads of Foreign Intelligence, 1920-2005

Appendix C

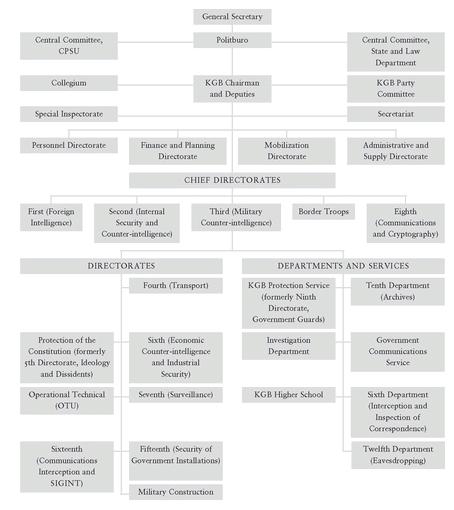

The Organization of the KGB in the later Cold War

Source: Desmond Ball and Robert Windren, ‘Soviet Signals Intelligence (Sigint): Organisation and Management’,

Intelligence and National Security

, vol. 4 (1989), no. 4; Christopher Andrew and Oleg Gordievsky,

KGB: The Inside Story of Its Foreign Operations from Lenin to Gorbachev

, paperback edition (London: Sceptre, 1991); and Mitrokhin.

Intelligence and National Security

, vol. 4 (1989), no. 4; Christopher Andrew and Oleg Gordievsky,

KGB: The Inside Story of Its Foreign Operations from Lenin to Gorbachev

, paperback edition (London: Sceptre, 1991); and Mitrokhin.

Other books

Blood Crazy by Simon Clark

The Hidden Boy by Jon Berkeley

Sand Glass by A M Russell

Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition by Howard Schilit, Jeremy Perler

The Door by Magda Szabo

Sucker Punch (TKO #4) by Ana Layne

On Fire by Stef Ann Holm

Viridian by Susan Gates

Dead Gorgeous by Malorie Blackman

Tik-Tok by John Sladek