The Witling (6 page)

The guards were unstrapping the two prisoners now, pulling them to their feet. But Yoninne clung tenaciously to the conversation. And Ajão could see why now. The nobleman—Pelio—and his entourage were descending the wooden stairs from the upper decks. Ajão could see the somber, almost sullen, look on the boy’s face, and hear the cheerful conversation of those around him. Poor Yoninne.

“I see what you mean,” said Leg-Wot, her voice strangely tense. “So that’s another reason why the Azhiri jump from water.”

“I think he’s coming down here, Yoninne,” said Bjault.

Leg-Wot bit her lip, nodded stiffly. “What … what shall I do?”

“Just be friendly. Try not to tell him too much about our origins, at least until we’re sure the Azhiri really are technologically backward. But most important,

get that maser.

”

Pelio and company had reached the first deck and were walking purposefully toward the Novamerikans. Finally Yoninne said softly, painfully, “Okay … I’ll try.” For an instant he thought she might break beneath the pressure of her embarrassment and fear, but then their guards urged them to attention, and they were confronted by Pelio.

O

ne of Pelio’s favorite places was his study in the North Wing of the Summerpalace. The room was an intricate melding of blackwood and quartz. It perched near the crest of the tree- and vine-shrouded ridge that ran all the way around the North Wing’s private transit lake. From one window he could see the white sands and palms surrounding that lake, while from another he could look over the ridge at the ocean below, and the strip of green that was the coast of the southern continent of the Summerkingdom. The room had been designed so that a warm breeze always floated from one window or another, and no matter what the time of day, sunlight filtered down upon his writing desk in shades of green.

There were many rooms in the palace that had better views, and there were many rooms more finely constructed and more beautifully furnished. But

this

room was something none of the thousands of others were: it had been designed especially for him and his … peculiarities. Pelio was eternally grateful that his father permitted him quarters that, by the standards of imperial architecture, were so grotesque. (Or perhaps the king simply realized that with this room it would be easier to keep the prince out of the public eye.) Whatever the reason, the study had been a wonderful gift: it really wasn’t a single room, but was partitioned into five separate chambers, connected by

doorways—

just like some peasant’s hutch in the far north, where transit pools were an uncomfortable inconvenience.

Thus the “study” was actually a bedroom, a dining room (with iceboxes that could store up to a nineday of meals), a library, and a bath. Once within his study, Pelio was independent of the servants he normally needed simply to move from one room of the palace to another. Often the prince-imperial stayed ninedays at a time here, alone except for Samadhom and the servants who brought food.

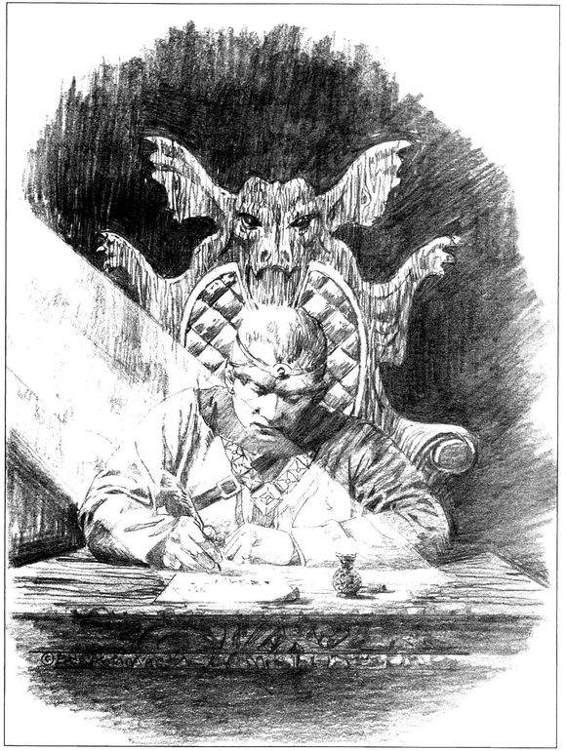

Now Pelio sat at his blackwood writing desk with its glasslike surface and engargoyled drawers, and tried to find just the right words to put across the deception he was planning. The first part of the letter came easily. It was in the antique format prescribed by royal etiquette:

To: Our noble cousin Ngatheru-nge-Monighanu-nge-Shopfelam-nge-Shozheru —

Actually, Ngatheru was in the fifth tier of the peerage, but on the other hand, he did hold a direct commission from King Shozheru. Besides, it should flatter the old scoundrel to be addressed with only two names between his and the king’s.

From: Pelio-nge-Shozheru, Prince of the Inner Kingdom, Emperor-to-be of All Summer, and First Minister to the King-Imperial.

That last title was an archaic touch, but perhaps it would give Ngatheru the idea that Pelio had been delegated the royal powers usual to an heir apparent of Pelio’s age. Hopefully, the baron-general was far enough from the gossip of the court that he did not realize just how completely Pelio was frozen out of the ruling circles.

On this seventh of the fifteen nineday of Autumn in the Year of Shozheru 24, we bid thee GREETINGS:

So much for what came automatically. Pelio’s pen poised above the vellum. The sap oozing from the pen’s cut nib had almost hardened before he set the device back in its holder. He was at a loss for words; rather, he was terribly afraid his lies would be transparent to Ngatheru. The girl’s dark, elvish face rose from memory to blot out the letter before him. She had been so reserved when he talked to her on the yacht yesterday. She carried herself like one freeborn, as though she didn’t even know she was a witling. She spoke respectfully, but he almost had the feeling she thought herself superior to those around her. Both she and her immensely tall companion were strange creatures, filled with contradiction and mystery. All of which added to his resolve to keep her near—even if it meant lying, even if it meant usurping the royal prerogative.

Pelio sighed and retrieved the pen. He might as well get something down. After all, he could always redraft the thing before he sent it. Begin with the usual flattery:

Your continued command of our garrison at Atsobi is a great comfort to us, good Ngatheru. We still remember with pleasure your eviction of the Snowfolk squatters near Pfodgaru just one year ago. Our northern marches are often perilous, and we have great need of someone with your vigilance to stand guard there.

In particular, we took note of your alert interception of two trespassers on 4/15/A/24. As you know, the king is ever desirous of having current and—as nearly as possible—firsthand knowledge of such activities. So it was that we took it upon ourselves to visit Bodgaru and assume personal custody of the captured individuals.

That was a neat touch. Without quite saying so, he had managed to imply that his father was behind his actions. The only danger was that the baron-general might have already reported the capture. But that was unlikely. Cousin Ngatheru had a reputation for independence—some might say treasonous arrogance. He did his job well, but he liked to do it all by himself. Chances were he had planned to keep his discovery secret until he had the whole affair wrapped up in a pretty package.

Pelio wondered again who had sent him the anonymous message describing what Ngatheru’s men had found in the hills north of Bodgaru. Obviously, someone was trying to manipulate him, just as he was trying to manipulate Ngatheru. But who? If Ionina and Adgao had not been so patently alien, he would have suspected the whole affair was an intricate trap, set perhaps by his brother and mother. Pelio shook his head and returned to the letter:

As you know, Good Cousin, the circumstances of this incident are mysterious and ominous.

We feel

How wonderfully ambiguous the royal “we”! that this matter must be handled with complete secrecy and at the highest levels. Any spread of information concerning this capture would endanger All Summer.

Threatening Ngatheru with high-treason charges should help keep his mouth shut.

Pelio finished with “Abiding affection and highest regard,” and signed his name. Actually, now that he looked at it, this draft didn’t seem too bad. He folded and refolded the triangular vellum until it was a ball less than two inches across. Then he dipped it in a reservoir of blood-warm sap at the corner of his desk and impressed the royal seal upon the bluish resin.

Samadhom slept near his feet, a golden hulk on the sun-warmed floor. The watchbear didn’t stir a hair as the prince crossed the room and pulled on the cord that emerged from a hole in the wall. Through the warm morning air came the clear sound of the bell set in the servants’ room down the hill. The ringer was something Pelio had invented himself, though he felt no pride for having done so: few people ever had use for such an invention. But without that bell and cord, he would needs be surrounded by his servants every minute.

Samadhom raised his head abruptly to look at the transit pool set in the floor at the middle of the room.

Meep,

he said questioningly. A second passed and a servant splashed lithely out of the water to stand at attention at the pool’s edge.

“Two things,” Pelio began with the casual abruptness of one who is rarely disobeyed. “First, have this message sent to Baron-General Ngatheru at Atsobi.” He handed the man the ball, its resinous covering now completely dry. “Second, I wish to question the”—

carefully!

he thought to himself. Be properly casual—“the female prisoner brought here yesterday.”

“As you say, Your Highness.” The man disappeared into thin air, not bothering to use the transit pool.

Show-off.

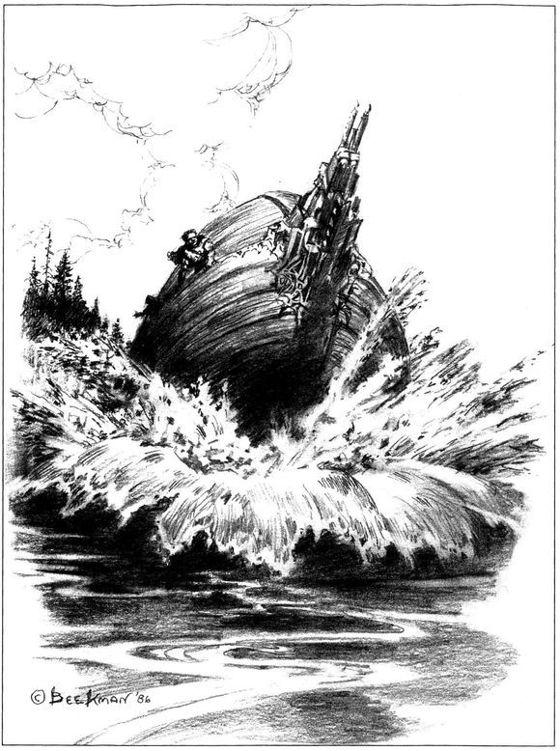

In a matter of minutes, his letter would be packed into the softwood hull of a message torpedo, and in a single jump teleported six leagues north, all the way to Ngatheru’s command bunker deep within the Atsobi Garrison. There, the shattered remains of the torpedo would be hacked apart and his message retrieved.

So much for the baron-general. If that message didn’t keep him quiet, nothing would. A much greater danger to Pelio’s plans lay in servants’ gossip. Fortunately, he could always rotate his household servants. The ones who served him now were from the royal lodge at Pferadgaru, way south of the Great Desert. Of course they knew he was a witling, but they didn’t know what little say he had at court. It should be many ninedays before they realized he was involved with a commoner witling, and even longer before they started gossiping outside their own group. Before that happened he would rotate them back to the marches of the Summerkingdom.

But Pelio saw that no matter how he worked it, he was running a terrible risk. It was always an embarrassment to the royal family when a prince dallied with a commoner. But if the commoner were a witling, embarrassment became scandal. And if the prince himself were a witling, then scandal became an eternal blot upon the dynasty. Should his deception be discovered, he would never be king.

And there was just one way his father could remove him from the line of succession … .

T

here was splashing from the pool and three guards dragged Ionina from the water. Pelio grimaced. He had not even senged the imminence of the arrival. Usually he had

that

much Talent.

The four stood at attention now. “Leave me to question the prisoner,” he said to the guards. One man started to protest, but Pelio interrupted, “I said, leave us. This is a matter of state. In any case, I have my watchbear.”

The guards withdrew and Pelio found himself staring at the girl. She wore the same black coveralls as before, only now they were soaked. The water dripped slowly down them to pool about her boots. What should he say? The silence stretched on for a long moment, broken only by the buzzing and crooning of gliders in the trees around the study. He knew how to order his servants, how to cajole his father, even how to manipulate lesser nobles like Ngatheru—but how do you speak to a prospective friend?

Finally: “Please sit. You have been treated well?”

“Yes.” Her tone was quiet and respectful, though she did not acknowledge the difference in their rank.

“I mean really?”

“Well, we would like more to live in a house with doors. You see, we can’t, we can’t—what is your word for it?”

“Reng?”

“Yes. We can’t reng. To us, a room without doors is a cage. But then Ajão and I are prisoners, are not we?”