The Witling (9 page)

B

y the time Yoninne arrived at the prison-cell-

cum

-guest house, twilight had darkened into night. One of the moons had risen over the rim of the ancient volcanic cone, and its silver-gray light sparkled off wavelets in the central lake, limned the sloping sides of the boats floating there, and turned the beach she walked along into a pale, curving strip. From somewhere across the lake, still in the shadow of the cone’s wall, there were sounds of laughter and splashing, and a pleasant smell that could only have been barbecue.

One of her guards—guides?—drew her off the sand onto a path that angled up the hillside into the palmlike trees. The moonlight scattered into triangular silver fragments as it sifted down, and the smell of green things hung all about. In the humid air, her dress was only beginning to dry, but the material was so soft and light that she scarcely noticed the dampness—while the flight suit she carried in one hand was still sodden, even though it had been lying on the windowsill all day long.

This was quite a change from her treatment that morning, when she had been hustled off a straw pallet in a doorless cell and unceremoniously hauled from one pool of water to the next. Now her guards were almost solicitous; after Pelio said good night they had even agreed to walk her to her quarters rather than teleport there.

Ajão had certainly been right about the boy Pelio. As the number-one son of the biggest wheel on the continent, he was spoiled rotten, but it hadn’t taken long to see that behind his bluster was a kind of soft-hearted naivete. That had puzzled her through most of the day until, there in that strange cold room, he confessed that he couldn’t teleport any more than she could. You’d think he was admitting to some terrible disease; poor guy, in a way perhaps he was.

That admission was just further evidence that the Azhiri needed no super-technology. Sure, they had simple crafts—ironworking and such-but all the fantastic things they did were applications of the “Talent” most of them were born with. She hadn’t really been convinced of this till she saw what passed for toilet facilities among the upper classes; the fixtures were carved from marble and quartz, yet the wastedisposal system was no better than a common outhouse.

All in all it had seemed safe to tell Pelio that no members of her race could teleport. And her admission had made the kid look so … happy.

Through the leaves and tree trunks she saw a flicker of yellow. The path wound on another fifteen meters, then opened onto a clearing set in the hillside. By the moonlight she saw a large cabin done in the usual stone-and-timber style—but this building had a

doorway

hacked through one wall. The flickering light from within painted a yellowish trapezoid on the mossy ground.

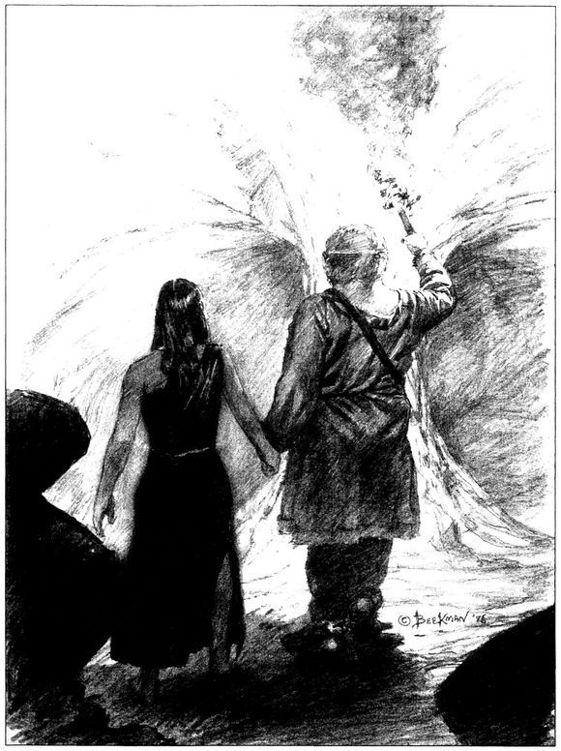

As she stepped into the fresh-cut doorway, Ajão Bjault looked up from the wall torch he had been examining. “Yoninne!” After a day filled with gray-green faces, his chocolate skin and frizzy white hair looked incongruous. The old man’s gaze flickered from Yoninne to the two Azhiri who still stood in the darkness beyond the room. “I didn’t hear you coming up. Are you all right?”

Yoninne smiled. Ajão’s hearing was so bad he would probably miss the crack of doom. She stepped into the room. Behind her, she heard the two guards retreat. “I’m fine. Just fine.”

The other looked at her a bit strangely. “How do you like this place?” he said. “They brought me here just before sunset. Quite an improvement.” Yoninne looked around. Like most isolated buildings she had seen that day, it had only one room, with a transit pool in the center. Pelio had been as good as his word: their new apartment was nowhere near as opulent as his quarters, but it looked comfortable enough. Yoninne curled up on one of the pillowed chairs and suddenly felt very tired in a kind of satiated way. Supper had been

good

. The lead and mercury in the local “edibles” would be lethal in the long run, but they certainly didn’t affect the taste of food.

Ajão still had a puzzled expression on his face. “I’ve been trying to make these torches burn brighter,” he said. “They’re not just simple pieces of wood. They have a wick structure … .” He stepped back from the torch’s wall bracket and peered out the doorway into the darkness. Then he turned back to Yoninne, “I don’t know why I’m so cautious; they don’t understand a word I’m saying.” Now that she looked at him more closely, she realized he was tired and jittery. And still he had the air of being unable to believe what he was seeing. “Did you have any luck, Yoninne?”

“Luck?”

He frowned. “The maser, Yoninne. The maser.”

“Oh, no. But don’t worry, we’ll get it some other …” Her voice stuttered into silence, and her peaceful mood vanished as abruptly as if she had been slapped in the face. She understood now the puzzled look in the other’s eyes, and realized just what he was seeing: Yoninne Leg-Wot, the stubby, flatchested pilot. She looked down at herself, saw the thing she had called a dress—a short green kilt, barely large enough to hold her wide hips. She had been running around like a fatassed fool all day. Leg-Wot bounced onto her short legs, felt a hot flush of humiliation rising to her face. And this senile bastard just stood there pitying her.

“God damn you, Bjault,” she choked out as she stumbled across the room to the lavatory alcove. She yanked the curtain shut and ripped off the skimpy kilt. Her flight suit was still damp, but she pulled it on with a few quick motions, and zipped the diagonal fastener. She stood silently for several seconds watching herself in the wall mirror. Wearing the flight suit, she was her usual coolly efficient self.

She slid the curtain aside, and walked back across the room, the water in the suit’s boots making faint

squishsquishsquish

sounds. The old man still hovered nervously by the far wall. “You know, Yoninne,” he said in that diffident, hesitant way of his, “you’re not the only person who’s had a bad time today. Until this evening I was cooped up in that cell, wondering what they had done to you … and what they were going to do to me. I—”

Leg-Wot raised a slablike hand, “Okay, Ajão, I apologize for blowing up. Let’s forget it.” She settled her bulk onto the pillows, and felt the cold material of the flight suit press comfortingly against her back. “Now, do you want to hear what I’ve been up to today?”

The other nodded, then sat down on a facing pillow-chair as she began. “First of all, I’m convinced that your ideas about Azhiri teleportation are exactly correct. I was shuttled all over the palace today. Most of the time I could keep the sun in sight, so I was able to make rough estimates of how far and in what direction we had moved, and those estimates agreed pretty well with the ‘lurches’ I felt—just like you predicted.” Yoninne was only an adequate computer tech, but as a “seat-of-the-pants” hot pilot she was outstanding, the best aircraft pilot in the Novamerikan colony. She had an uncanny feel for accelerations in rotating frames of reference, and this was just the ability she had used to keep track of her position today. Sometimes Yoninne wished she had lived during the time of the Last Interregnal War on Homeworld, when aerial combat made its first and only appearance in that planet’s history. She could have shown those old “aces” a thing or two.

“Anyway, this Pelio kid showed me around the overgrown park he calls a palace.” Leg-Wot went on to describe the places she had seen: the hedgework that girdled the side of a mountain, the mammoth treehouse. Bjault’s questions brought out a hoard of detail, and they talked for several hours—till she thought the archaeologist probably had a clearer vision of what she had seen than she herself did.

The torches were burning low by the time he returned to the question he had asked at the beginning of the evening. “But you weren’t able to persuade this Pelio to show you our gear?”

“Uh, no … and that’s really a strange thing. I told you the boy is lonely, that he can’t teleport himself like the others. I think I’ve got him wrapped around my little finger. We were actually on our way to some high-security area where they’ve stashed our stuff. Then these two other characters showed up; they rank lower than Pelio—one of them was his brother. But somehow it really upset him to see them. It was almost as if he had been caught doing something he shouldn’t. He made up some kind of lie about who I was, but I didn’t understand all the words.”

Finally Bjault had no more questions. The night beyond the doorway was slowly cooling. In the silence, the faint stridulation of the lagoon’s tiny mammals sounded loud. “You’ve done well, Yoninne,” he said. “My confinement has scarcely slowed our progress, I’d wager. If you can just stay in Pelio’s good graces long enough to get another crack at that maser, we’ll get ourselves rescued yet.” He paused, and an impish look softened the lines of strain and age in his face. “I’m just glad you don’t speak Azhiri any better than you do.”

“Huh? Why the hell is that?”

“Because you haven’t had a chance to pick up any swear words. Your vocabulary—mine, for that matter—has all the purity of a child’s. It has to, since children are about the only people we’ve had a chance to listen to.”

Leg-Wot bit back an angry retort. She’d rather not let him see how mad such remarks made her. “Don’t worry, Bjault. I’m learning.”

With that the committee of two adjourned for the night. They tried to rig a curtain across the doorway, but finally had to settle on stuffing one of the largest chairs into the opening. It didn’t really block the way, but it would slow anybody—or anything—trying to enter. The transit pool was harder to block, since they couldn’t see how to drain it. Finally they gave up, Bjault doused the now-guttering torches, and they retired to their separate couches. Leg-Wot pulled the coverlet over her head and quietly shed the protection of her clammy flight suit.

She lay awake long after the old man’s breathing became loud and regular. With the torches out, the land beyond the doorway was flooded with light. The first moon still hung out there above the cone’s curving lip, but now the second, larger moon had risen, to shine several degrees above the first. They were both a common grayish brown, like the basaltic moons of a thousand other planets, but now they were so close together she could see the subtle difference in their hues. They were at last quarter but their light was so bright it made a complex net of double shadows across the broad-leafed trees that stretched downward from the cabin. The skittering and rustling continued as loudly as before. It was an altogether different music from the night reptiles of Homeworld or even the insects she had heard on Novamerika, yet it had a certain attraction.

What would she do tomorrow? She thought of the green scrap of cloth she had discarded. Unless she had broken the clasp on it, it was still wearable. But she’d be damned if she’d make a fool of herself again! That spoiled kid would just have to get used to her wearing a flight suit. Leg-Wot felt her teeth gritting together, and tried to relax. She knew how much was at stake here, how important it was to play up to Pelio. Without him, they would be without protection, and—more important—they would have no way of recovering their equipment. If word didn’t get back to Novamerika, it might be more than a century before the new colony would risk its resources by landing here again, more than a century before they would discover this world’s great secret.

She glared out onto the moonlit landscape. There was really no help for it. After all, it hadn’t killed her to wear the thing.

Pelio

obviously didn’t think she looked ridiculous, and he was the person she had to manipulate. If one more day’s humiliation was the price of getting that maser, then she would pay it.

T

his time there were no hitches. Again they went to the place Pelio called the Highroom, but now they found the special servant who could jump them into the Keep itself: they emerged from the transit pool into a vast, pale-lit emptiness. The wan light came from scattered greenish patches that seemed to float in the dark. It took Yoninne several seconds to realize that those patches were the same funguslike material that had hung gangrenously from the walls of their dungeon in Bodgaru. But this place didn’t stink, and the floor was dry and unslimed beneath her feet. The room was an ellipsoidal cavern so long that the glow patches on the far wall were little more than green stars in the dark. Their transit pool was set on a fifty-meter-wide ledge that shelved out from where the cavern’s wall began curving over into the ceiling. Abruptly Yoninne realized that nearly half the greenish lights were actually reflections in an oval lake that filled much of the cavern’s floor. The water was so still that she might never have noticed it if she hadn’t seen the faintly reflecting hull of a boat moored against the near shore.

They started down the steps that led from the shelf. As usual, Pelio’s servants trailed a fair distance behind. “This is my family’s Keep,” said the prince with evident pride, “probably the best angeng” (?) “in the world.” She had a hard time following the rest of his description; there were too many words that she did not recognize. But she was able to piece together the overall story. Originally the Keep had been a natural cave, with only one small entrance, and that near the Highroom. The Guild had senged (felt? seen? sensed?) the cave’s location and sold the information to the Summerkingdom. Pelio’s ancestors had entered the cave and enlarged it to its present size. The single entrance had then been blocked. From then on, security was relatively easy to maintain: the Azhiri could not teleport to any point that they could not seng. And if you weren’t a Guildsman, the only way to seng a location was to travel—by some means other than teleportation—to within a few meters of it. After that, apparently, the spot could be senged from any distance.