The Way of the Knife (43 page)

Read The Way of the Knife Online

Authors: Mark Mazzetti

Tags: #Political Science, #World, #Middle Eastern

Hafiz Muhammad Saeed (center), the charismatic leader of the militant group Lashkar-e-Taiba. The group, using a political front organization, operates openly around Lahore and is believed by American officials to maintain close contacts with the ISI. In early 2011, a group of CIA officers in Lahore—including Raymond Davis—were trying to gather intelligence about Saeed and his group.

Admiral Mike Mullen (far left), chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was one of the few senior Obama administration officials who tried to maintain close relations with Pakistani officials. He made frequent trips to Islamabad and developed a friendship with General Kayani (second from right). The warm relations ended after Mullen became convinced that the ISI was supporting the Haqqani Network’s attacks in Afghanistan.

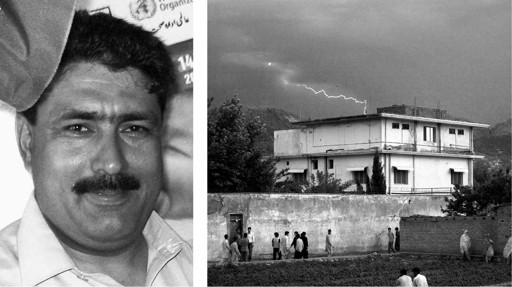

Dr. Shakil Afridi (left), a Pakistani physician, was hired by the CIA to run a vaccination program in Abbottabad. The CIA was hoping that the ruse would unearth evidence that Osama bin Laden was hiding in a large compound (right) in the town.

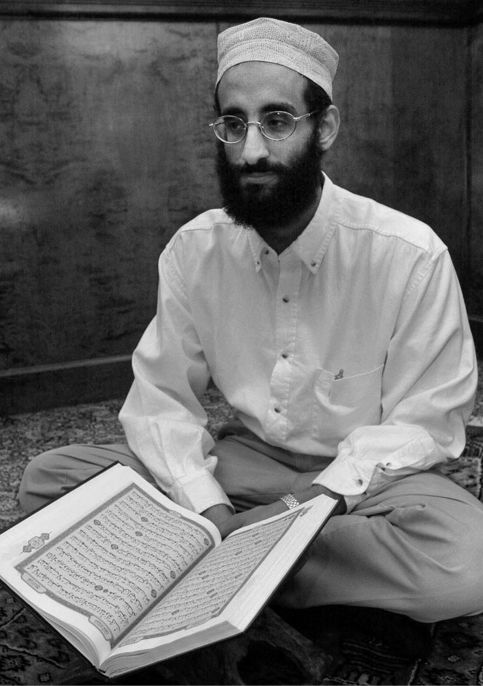

Anwar al-Awlaki, a radical cleric born in the United States, was killed by a CIA drone strike in Yemen in September 2011. Two weeks later, another drone strike mistakenly killed his teenage son.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Writing a book involves making hundreds of decisions, and with a first book it’s very difficult to know how many of those decisions are good ones. I am extraordinarily lucky that one of the first decisions I made was among the best, which was to hire Adam Ahmad to be my research assistant. From our first meeting, over coffee in Chicago, where he was finishing his master’s, I could tell that Adam was bright, curious, and dedicated. He proved to be all those things and so much more. He was an absolutely integral part of the book during all of its phases. He researched documents, wrote background papers, organized endnotes, and in several cases managed to track down an Urdu speaker to translate documents and recordings neither of us could understand. When I arrived at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Jessica Schulberg joined the project and provided research help every bit as valuable as Adam’s. Jessica has a particular interest in Africa, and her ability to unearth information about Somalia and North Africa was awe inspiring. She is a clear thinker and is wise beyond her years. During the course of writing this book, I have come to value not only Adam and Jessica’s guidance but also their friendship. They both have long and bright careers ahead of them, whatever paths they choose.

It was my great fortune to spend fifteen months at the Wilson Center, the best research institution in Washington. The Wilson Center gave me a professional home, fascinating and supportive colleagues, and access to a vast library run by a crack team. Thanks to Jane Harman and Michael Van Dusen for accepting me as a Public Policy Scholar and for running such a terrific operation. A very special thanks to Robert Litwak for being a constant source of insight and humor as I went through the painful process of writing the first draft of this book.

It is my great honor to be a reporter for the

New York Times,

and I am grateful to Jill Abramson, Dean Baquet, and David Leonhardt for allowing me to take a leave from the paper to work on this project. When he was my boss in Washington, Dean encouraged me to examine the unexplored aspects of the secret wars—to write the stories that others weren’t writing. Some of the issues I wrote about for the newspaper during that period are explored in greater depth in this book. My friends and colleagues Helene Cooper, Scott Shane, and Eric Schmitt gave me encouragement and guidance throughout this process, and Scott and Eric took on a great deal of extra work while I was on book leave. I can’t thank them enough. In addition to those three, the national-security team in the Washington bureau is a collection of the best reporters—and most entertaining people—anywhere in journalism. Particular thanks to Peter Baker, Elisabeth Bumiller, Michael Gordon, Bill Hamilton, Mark Landler, Eric Lichtblau, Eric Lipton, Steve Myers, Jim Risen, David Sanger, Charlie Savage, and Thom Shanker. I am very lucky to work with them and the entire Washington bureau. Thanks also to Phil Taubman and Douglas Jehl, two former bosses at the paper with vast experience in intelligence reporting, who helped me greatly as I was beginning to cover a new beat.

This book would never have happened without Scott Moyers, who in his previous incarnation as a literary agent urged me to look deeper into the themes that I was writing about in my articles for the

New York Times.

Then, after Scott became the publisher of The Penguin Press, I was lucky enough to get him as my book editor. He sees the big picture and pushed me to write as expansively as possible about the changing nature of American war and its impact. I appreciate the time he gave me to make sure the reporting for this book was right, and he provided a steady hand during the editing process. He proved that great book editing is possible even under very tight deadline pressures. Thanks also to Ann Godoff, the president and editor in chief at Penguin Press, for taking a leap on this project and for ensuring that the book could be published swiftly, at a time when these issues need far more public discussion. Mally Anderson at Penguin Press ensured that the various pieces of the book met their deadlines, and I’m very grateful to her for patiently guiding me through what was a very mysterious process. It was good having her calm voice at the other end of the phone.

Rebecca Corbett, a friend and editor at the

New York Times,

probably has no idea how much better this book is as a result of her guidance, patience, and savvy. She pored over several drafts of the book, pushing me to dig deeper in the reporting and explain myself better in the writing. She has a keen eye for detail and for making characters come to life. Our lunches at The Bottom Line not only helped me organize my reporting but also helped enormously in constructing the book’s narrative. The discussion was much better than the food.

My agent, Andrew Wylie, has been a confidant since the earliest stages of writing the proposal for this book, and I am grateful to him for taking me on as a client. He’s a true professional, and he gave particularly wise counsel during a nerve-racking day in New York as I had to make a decision about publishers: He told me to go with my gut. “Stop worrying,” he said. “Life’s too short.” He was right.

My

New York Times

colleague Declan Walsh, in Islamabad, was kind enough to put me up during my time in Pakistan. Besides being a terrific reporter and a source of immense wisdom about what may be the world’s most complicated country, Declan runs what is no doubt Pakistan’s finest guesthouse. Thank you to everyone at the Islamabad bureau for making my reporting trip to Pakistan so productive.

I am in great debt to my friends who cover national-security issues for other news organizations. The work that they do to shed light on dark corners has informed this book immensely. Particular thanks to Greg Miller, Joby Warrick, Peter Finn, Julie Tate, and Dana Priest, of the

Washington Post;

Adam Goldman, Matt Apuzzo, and Kimberly Dozier, of the Associated Press; and Siobhan Gorman, Julian Barnes, and Adam Entous of the

Wall Street Journal.

We all may compete fiercely against each other, and curse each other when we are forced to match a competitor’s story at 10

P.M.

, but in the end we’re all on the same side.

The debt that I owe to my family is one that I can’t possibly begin to repay. My parents, Joseph and Jeanne Mazzetti, taught me to be curious and to be humble. But most of all they taught me to be honest, and I hope they are as proud of me as I am of them. My sisters, Elise and Kate, are the two best friends someone could have, and they—along with their husbands, Sudeep and Chris—are role models for me in the way that they live their lives and raise their families.

The single person who has contributed the most to this book is Lindsay, my wonderful wife. From our very first discussion about the possibility of me writing a book, while walking in Riverside Park in New York, Lindsay’s support was unwavering. She read and edited drafts of the book, offered suggestions, endured my insomnia, and provided encouragement during the times that I thought I was taking on more than I could handle. I couldn’t possibly have done this without her, and I love her very much.

And to Max, my son. Max was born when I was in the early stages of this project, and he has changed my life in ways I’m just beginning to understand. I can’t wait until he is old enough to read this book. I cherish the memories of the mornings we spent together during the first few months, and of the smiles he delivered when I came home at the end of particularly frustrating days of book writing. They put things in perspective. There is a great deal of pain and heartache in the world, but it is a far better place with Max in it.

A NOTE ON SOURCES

It is a great challenge to write an account of an ongoing war that, at least officially, remains a secret. This book is the result of hundreds of interviews in the United States and overseas, both during my years as a national-security reporter and during my book leave from the

New York Times.

I tried as much as possible to convince the people whom I interviewed to speak for the record, and those who agreed are cited by name both in the main text of the book and in the endnotes. I also conducted scores of interviews on “background,” where I allowed sources to speak anonymously in exchange for their accounts of American military and intelligence operations, the vast majority of which remain classified. Although this is hardly ideal, I believe it is a necessary evil to ensure that trusted sources are able to speak candidly.

Using anonymous sources is always a risk, and as a national-security reporter I have learned that some sources can be trusted far more than others. For this book I have relied heavily on people whose information I have come to trust over the years. To the extent I am able, I have used the endnotes to give more information about who provided specific information, even if I did not use their names. On some occasions, usually because material is particularly sensitive, I presented information that does not have designated endnotes. In these instances I made sure that I could verify the information from multiple sources. When I recount conversations between two or more people, I have used quotation marks around the dialogue only when I am confident that my sources have provided an accurate recollection of the conversation.

I have tried as much as possible to draw on open source material and declassified government documents. In this effort, I have been helped by the work of several different organizations. The National Security Archive, at George Washington University, works tirelessly to get government documents declassified under the Freedom of Information Act, and I am enormously grateful for their efforts. The SITE Intelligence Group is the best resource for monitoring the writings and public statements of militant groups in Pakistan, Somalia, Yemen, and other countries, and I have drawn extensively on SITE’s work. A large number of the U.S. government documents cited in this book were first made public by WikiLeaks, the antisecrecy organization. The WikiLeaks database has become an important resource for journalists and historians trying to better understand the inner workings of American government.