The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (19 page)

Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

The first concern, the day after the fire was brought under control, was to recover the body of James Braidwood. It was known where he had been standing when the wall collapsed, but such was the devastation that it was to be three days before his body was located. When it was, ‘The crowds of persons who blocked up every avenue leading to the ruins manifested the greatest eagerness to catch a glimpse of the spot where the unfortunate gentleman fell, and when it was known that his body had been disinterred the excitement became very great...almost every person within the barriers flock[ing] to the fatal spot.’ More touchingly, Fire Engineer Tozer, who was in charge of Tooley Street station and had previously worked directly under Braidwood as his chief clerk, cut off Braidwood’s epaulettes and buttons from his uniform, giving them to the foremen of the fire service as a memento of their great chief.

Braidwood’s funeral became a civic mark of appreciation of the man who had modernized the fire service, who had, in that age of chimney fires and dangerous workshops, done so much to keep the city safe. The fire service planned an elaborate public procession, but even they were taken by surprise by the public response. On 29 June, crowds of bystanders staked out positions long before the procession formed at Watling Street, in the City. Shops had closed; shutters and blinds were drawn as a sign of respect. Every bell in every City church rang a funeral peal (apart from St Paul’s, which was reserved for funerals of the royal family, or the serving Lord Mayor). ‘No one had anticipated that the ceremony of burying the lamented chief of the Fire-Brigade would excite an almost unprecedented degree of public interest. The police seemed bewildered to know how to manage the vast host that lined the thoroughfares...From the very first step a difficulty was experienced in obtaining a clear passage for the

cortège

, and although vehicles were turned into bye-streets, and the roadways stopped up against fresh comers, yet the struggle was incessant, and the long line was compelled to halt many times during the afternoon.’

The Times

gave the order of the funeral procession as it left Watling Street for Abney Park Cemetery, in Stoke Newington:

A body of the City Police.

The London Rifle Brigade, with its band...

to the number of about 700.

The 7th Tower Hamlets...with various other

Volunteer Rifle Corps, to the number of about 400.

Friends of the deceased in mourning.

Metropolitan Police.

Superintendents.

Inspectors.

Constables of the various divisions, to the number of about

1,000 (four abreast).

City Police.

Inspectors.

Constables of the various divisions, 350 (four abreast).

The Waterworks Companies.

Superintendents.

Inspectors.

Band of the Society for the Protection of Life from Fire.

The Secretary, Mr. Low, Sen.

Fire Escape Conductors (four abreast).

Charles Henry Firth,

Captain of the West Yorkshire Fire Brigade Guard Volunteers,

accompanied by two privates and a deputation from the

Lancashire and Yorkshire Fire Brigades.

Private Fire Brigades: –

Mr. Hodges’s, Lambeth,

Mr. Burnet’s, Lambeth,

Messrs. Price’s, Vauxhall,

Messrs. Beaufoy’s, Vauxhall,

Messrs. Lennox and Co.’s, Millwall.

Local Brigades: –

Hackney. West Ham.

Shoreditch. Crystal Palaces.

Islington. Whitechapel.

Bow. Wapping.

Stratford. Greenwich.

Superintendent White, of the Gravesend Police and

Fire Brigade and others.

Pensioners and Friends

London Fire Engine Establishment.

Junior Firemen.

Senior Firemen.

Sub Engineers.

Engineers (two abreast).

The Ward Beadle of Cordwainers’ Ward.

The Undertaker.

Two Mutes.

The Pallbearers:

Mr. Swanton, engineer.

Mr. Fogo, foreman.

Mr. Bridges, foreman.

Mr. Gerrard, engineer.

Mr. Henderson, foreman.

Mr Staples, foreman.

A plume of feathers.

THE HEARSE.

The Chief Mourners:

Mr. James F. Braidwood

Mr. Frank Braidwood

Mr. Lithgow Braidwood

Mr. Charles Jackson

Fifteen Mourning Coaches

Containing the relatives, friends, and committees of the

London fire engine establishments.

Private carriage of the Duke of Sutherland.

Private carriage of the Earl of Caithness.

Private carriage of Dr. Cumming [the officiating clergyman].

And other private carriages.

Most unusually, in an age when sending an empty carriage was considered to be a significant mark of respect, the Duke of Sutherland and the Earl of Caithness were actually present.

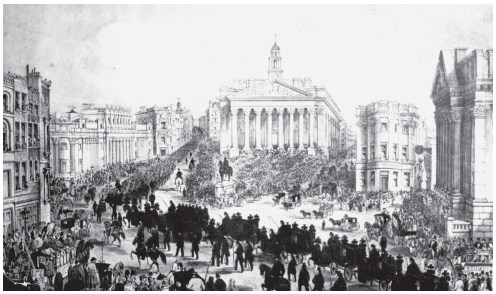

The procession moved slowly through an ‘immense multitude’ that had gathered in homage to Braidwood; ‘in the front of the Royal Exchange, and all round this space the roofs and windows were thronged. As the procession slowly approached, the troops with arms reversed, and the bands slowly pealing forth the Dead March, the mass of spectators, as if by an involuntary movement, all uncovered [their heads], and along the rest of the route this silent token of respect was everywhere observed.’ The crowd was so thick that, despite an escort of mounted police, the cortège took three hours to cover the four miles to the cemetery in Stoke Newington, with thousands of silent onlookers lining the route the entire way.

At Abney Park, the body of James Braidwood, aged sixty-one, was laid to rest beside his stepson, also a fireman, who had died on duty six years earlier. Braidwood Street, off Tooley Street, today continues to commemorate both the worst fire London had seen since the Great Fire of 1666, and the heroic service rendered the city by the founder of the modern fire brigade.

5.

THE WORLD’S MARKET

Saturdays were Covent Garden market’s biggest day, when the costermongers stocked up with produce to sell over the coming week, up to 5,000 of them heading for the market with donkey carts, with shallow trays or with head-baskets.

46

By the 1850s, London’s main produce market had long overspilled its bounds, covering not just the Piazza it was designed to occupy, but spreading over an area ‘From Long Acre to the Strand...from Bow-street to Bedford-street’, for several hundred yards in either direction: ‘along each approach to the market...nothing is to be seen, on all sides, but vegetables; the pavement is covered with heaps of them waiting to be carted; the flagstones are stained green with the leaves trodden underfoot...sacks full of apples and potatoes, and bundles of brocoli [sic] and rhubarb are left...upon almost every doorstep; the steps of Covent Garden Theatre are covered with fruit and vegetables; the road is blocked up with mountains of cabbages and turnips.’

This description came a quarter of a century after the new market had first been planned. In 1678, the Dukes of Bedford, who owned the land, had been granted a 250-year lease for a market, and for nearly two centuries what had been called a market had been merely a collection of wooden sheds and stalls. In the early 1820s, with the lease due to expire, the Bedford Estate received permission to build permanent structures in the centre of the Piazza, expanding beyond the original square itself, and soon sellers operated in a landscape of half-built premises. By 1858, there was a central

structure of wrought iron. The old Piazza Hotel, which had backed on to Covent Garden theatre, and had long served as the entrance to the pit and box seats in the theatre, had been demolished. In its stead Floral Hall, a building to house the flower sellers, was being constructed in the style of the Great Exhibition’s Crystal Palace. (In a neatly circular fashion, Floral Hall once again serves not the market but the theatre, providing the Royal Opera House’s box office and refreshment bars. One section of the Piazza’s central structure was rescued when the market was demolished in the 1970s, and in the early twenty-first century was re-erected in the Borough market.)

Before dawn the traffic converged on the streets surrounding the main markets. The waggoners were recognizable by their countrymen’s smocks, with velveteen breeches and leggings, or their gaiters, made of canvas, linen, wool or leather, tied below the knee and again at the ankle, or buttoned or buckled on, all designed to prevent the roads’ endless mud from making a pair of stockings unwearable after a single outing (see Plate 1, top row right, and bottom row third from right). Carts were an ongoing problem: slow to arrive, cumbersome to turn, difficult to leave while their drivers took their goods into the market. As a result queues up to a mile long were not unusual. In the late 1840s, one enterprising boy carved out a job for himself by offering a solution. Like many homeless street children, Bob had haunted the market, running errands and fetching and carrying for stallholders in return for food, or a penny. Winning their trust, he promoted himself to the self-created position of ‘market-groom’: now when the carts had been driven as close to the market as possible, the waggoners were met by Bob, who held their whips as a sign of authority and then kept watch, preventing the donkeys and horses from wandering off, or straggling into the roadway, or entangling themselves with other carts. He also stopped the street children from pilfering from the carts, as well as ensuring that the animals themselves didn’t pilfer, by munching the produce of the cart in front of them.

Business, in summer, started before three o’clock, when ‘the crowd, the bustle, the hum’ of the morning really began. There were three official market days at Covent Garden – Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays – but for most of the century the market was in operation every morning. The

market traders who walked in from the country wore smocks covered by a thick blue or green apron; if their job were of a particularly messy or unpleasant type – skinning rabbits, for example – this apron was in turn covered by a piece of sacking tied on top. In the main square were the flower, fruit and vegetable sellers. Potatoes and ‘coarser produce’ were on one side, with more delicate fruit and vegetables set apart, and potted plants also given their own section. Cut flowers were displayed separately, where ‘walls’ (wallflowers), daffodils, roses, pinks, carnations and more could be found in season. The size of the market and the variety of colour were dazzling. When Tom Pinch and his sister come up from the country in

Martin Chuzzlewit

, they stroll through the market in a daze, ‘snuffing up the perfume of the fruits and flowers, wondering at the magnificence of the pineapples and melons; catching glimpses down side avenues, of rows and rows of old women, seated on inverted baskets, shelling peas; looking...at the fat bundles of asparagus with which the dainty shops were fortified as with a breastwork’.

Fruit and vegetables were the main focus, while around the sides subsidiary sellers set up, selling to other traders: horse-chestnut leaves to put under exotic fruit displays; ribbons and paper to make up bouquets; or tissue paper ‘for the tops of strawberry-pottles’, those conical wicker baskets shaped like witches’ hats, without which, it appeared, no strawberry could be sold. (See illustration on p. 22: the couple at top right carry two pottles.) On the railings at the edge of the Piazza hung many more baskets for sale, usually watched over by Irishwomen ‘smoking short pipes’ and calling out, ‘Want a baskit, yer honour?’ In the 1840s, these women wore loose gowns looped and pinned up out of the dirt, showing their thick underskirts and boots; on their heads were velveteen or straw bonnets, with net caps underneath. Men and women alike wore luridly coloured silk ‘kingsman’ kerchiefs around their necks.