The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (17 page)

Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

The railways also transformed people’s notion of what could be considered a commuting distance. Until 1844, trains were too expensive, even in third-class, to be used by the working classes for their daily commute. In that year, however, the government, in exchange for lifting a tax on third-class carriages, laid down that all railway companies had to run at least one train daily with fares of no more than 1d per mile. Even so, average fares still mounted up to £1 weekly, the entire weekly income of many skilled, well-employed artisans. But slowly workers did begin to move out of the city centre, as these so-called parliamentary trains (also known as working-men’s trains) gradually made it possible for them to live in slightly more salubrious conditions for the price of an inner-city slum rent, or perhaps even less, funds that could then be reallocated to travel. Even so, these working-men’s trains were not attractive in and of themselves. Officially they were required to travel at a minimum of twelve miles per hour, but they were notorious for being regularly shunted on to sidings to give priority to trains carrying first- and second-class passengers. The companies initially saw these working-men’s trains as a political gesture and did not expect them to make a profit. The day’s single parliamentary train was usually scheduled to arrive

at the London stations well before dawn, to get the legal requirement out of the way, with the service from Ludgate Hill to Victoria, for example, departing at 4.55 a.m. and arriving at Victoria at six.

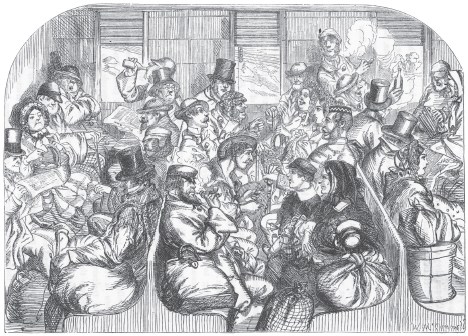

For the privilege of being shunted aside, until the 1850s the passengers in the third-class carriages stood in cars without benches or even roofs, exposed to rain, sleet and snow as well as the soot and smoke from the engine. There were no doors either, but as in cattle-cars a flap on one side of the carriage folded down to provide access. (The conditions gave rise to a series of jokes along the lines of ‘A man was seen yesterday buying a third-class ticket...The state of his mind is being inquired into.’) These carriages were more dangerous than the trains in general – in 1841, eight labourers from the building site at the new Houses of Parliament were thrown out of their open wagon and killed when the train they were travelling on ran into a landslide.

44

Some passengers actively enjoyed this form of travel: ‘the jolly part was coming down in the train we were in an open carrage the thurd class...but some times the sparks flu about and one woman got a hole burnt in her shawl. there was no lid to our carrage like some of them.’ However, the author of this paean was Sophia Beale, aged eight, to which she added the proviso, ‘I should not like to go in these carrages in winter.’ Second-class was little better, with bare benches holding five a side facing each other. Ventilation came via a small square of wooden louvres on the door, sometimes, but not always, covered by a pane of glass. ‘Smoking, snuff-taking, tobacco-chewing are all allowed,’ said one visitor sourly. Despite these habits, he added, only the ‘nobility and the wealthy’ travelled first class, as it was so expensive. In 1856, a ticket from Liverpool to London on the accommodation train – that is, a stopping train, not an express – cost 37s, or nearly a week’s salary for a well-paid clerk. Even the best-selling novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe declared, ‘first-class cars are beyond all praise, but also beyond all price,’ although she conceded, ‘their second-class are comfortless, cushionless, and uninviting.’ In first class, the passengers sat in ‘luxuriously upholstered’ seats in ‘nicely carpeted’ compartments, with plate-glass windows to let in the daylight, while after dark these carriages were lit first by rape-oil lamps, later with gas.

Omnibus travel and mailcoaches had increased the average speed of travel to nearly six miles an hour; with the railway this figure rose to over twelve, sometimes double that. By the late 1840s, therefore, areas that had traditionally been on the edges of London now housed commuters: Bow, Greenwich, Blackheath, Croydon, Woolwich, Gravesend and Charlton. By 1856, a town known as ‘Kingston on Railway’ made its priorities clear. (It later changed its name to Surbiton.) In 1851, there were 120 trains daily carrying commuters to and from Greenwich alone. Early railway lines, built to transport freight from Camden to the East and West India Docks, were soon transformed into commuter lines and promoted an east–west spread,

via Canonbury, Kingsland, Homerton and out to Bow. By 1851, this North London Railway transported 3.5 million commuters annually, half of whom were City commuters.

The first London station opened on the south side of London Bridge, and its twelve-minute trip to Greenwich replaced a one-hour coach journey. In 1837, Euston station opened, followed by a series of others: in 1838, Paddington and Nine Elms; in 1840, the Shoreditch/Bishopsgate terminus, which carried passengers to Romford, in Essex; in 1841, the station at Fenchurch Street in the City. In 1846, one contemporary estimated that, at the height of railway fever, if every company that had wanted to run a railway line into London had been given permission, over 30 per cent of the city would have been excavated for the purpose. To prevent even a fraction of this, in 1848 a Royal Commission on Metropolitan Termini drew a circle around the inner city, past which no railway would be permitted to run. In a shorthand description, it ran: Euston Road, City Road, Borough Road, Kennington Lane, Vauxhall Bridge Road, and Park Lane up to the Euston Road again. This boundary was breached almost immediately by a line from Nine Elms, at Battersea, to York Road (which became Waterloo) in 1848, but this was south of the river, and so somehow, mystically, to the West End and City men, it didn’t quite count. And despite two further breaches – Charing Cross (1864) and Liverpool Street (1874) – that line has held for 165 years: instead of lines coming into the city, as in most other European centres, London is ringed by railways.

45

(The underground, too, silently conforms to this loop.)

Initially, money was lavished on the construction of the railway lines, not on the stations. While many of London’s railway stations today have some Victorian elements remaining, they are all from the later part of the century. In the 1830s and 1840s, the stations started off very humbly indeed. Euston in 1838 had two platforms: the ‘arrival stage’ and the ‘departure stage’

(note the coaching word), from which three outward and three inward trains arrived and departed daily. (‘Inward’ and ‘outward’ were quickly superseded by ‘up’ and ‘down’ trains, meaning to and from London respectively, terms that survived until sometime after World War II.) In 1850, the Great Northern Railway’s station at Maiden Lane (the street is now York Way, while the station has become King’s Cross) was a temporary structure with two wooden platforms on the down side, between a gasworks and the tunnel for the new line. London Bridge in the 1860s had three stations: the Brighton station, the South-Eastern station and the Greenwich Railway station, the latter ‘a mean structure’.

As trains became more heavily used, attention turned to the stations. In 1849, Euston opened its Great Hall, a concourse and a waiting room, all poorly designed, because when they were planned no one quite knew how a railway functioned, nor what needs had to be served. (Most stations, for example, found space for stands on which were chained large Bibles, ‘for the use of the passengers while waiting for the train’.) At Euston, the new hall was vast – 125 by 61 feet, and 62 feet high – but the booking office was tucked into a cramped corner, with a secondary booking hall separated from the main concourse by the parcels office. Initially tickets could not be purchased on the train, and in some stations the booking office opened for just fifteen minutes before each train’s departure, causing great bottlenecks. At Euston a large area was given over to the Queen’s Apartments, a lounge for the use of the royal family should they be happening to pass through. It was rarely used and soon came down in the world with a bump, to become the ‘additional parcels office’.

Passengers too needed to learn how the system operated. Guides instructed them that, once they were on the train, ‘A glove, a book, or anything left on a seat denotes that [a seat] is taken’. Luggage, it was explained, was placed on the roof of each carriage (it was not until the early 1860s that specially designated luggage vans appeared). Until the 1880s, each carriage had doors opening only on to the platforms, with no connection from one carriage to the next. As a result all trains halted somewhere along the line to permit the conductor to walk along the track from carriage to carriage to check tickets. On the trains coming into Waterloo, the pause was made ‘on the

high viaduct over the Westminster Bridge Road’; by Euston ‘outside the engine-house’ (the Roundhouse at Camden); while outside London Bridge they stopped ‘close to the parapet of the 20-feet-high viaduct’ in Bermondsey. The Frenchman Francis Wey, in the 1850s, complained that his train was stopped while the tickets of nearly 2,000 passengers were checked: in third-class carriages, which were still mostly open-sided carts (‘in a country where it rains perpetually’, he wailed), the passengers were forced to wait ‘unprotected in the broiling sun between a rock and a brick wall’.

No matter how uncomfortable and inconvenient railways were, however, they were synonymous with modernity: by 1852, Dickens referred to the world he was living in as ‘the moving age’. Even a more prosaic man that same year acknowledged that he was ‘work[ing] at a railroad pace’ – that is, like a steam engine. For life was moving faster and faster, and even leisure was speeding up.

PART TWO

Staying Alive

1861: The Tooley Street Fire

B

y five o’clock on the evening of Saturday, 22 June 1861, the workmen in a row of warehouses were preparing for the Sunday shutdown in the repositories for the many goods traded in the City, sitting snugly along the river by London Bridge, near where the Borough High Street met Tooley Street. Scovell’s Warehouse was filled with hemp, saltpetre, tallow, cotton, rice, sugar and tea, and spices including ginger, pepper, cochineal and cayenne. Next to it stood Cotton’s Warehouse, then, further along the row of wharves, Hay’s Wharf, then Chamberlain’s Wharf, which traded in sulphur, tallow, saltpetre, jute, oils and paint.