The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (18 page)

Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

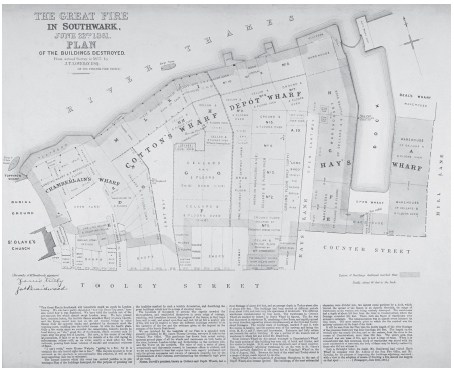

Almost everyone had left for the Sunday shutdown when a fire began, no one knew how, in the counting house at Scovell’s Warehouse. In minutes it had spread to four nearby buildings, quickly igniting the next four: ‘owing to the great quantity of tallow on the premises’ it raced through those too. Without pause, the flames then leapt the walls, reaching Cotton’s Warehouse and engulfing Hay’s Wharf. At last it set alight Chamberlain’s Wharf, with its lethal combination of wares.

There was fire north, south, east, and west, fire everywhere; red lurid flames in dense masses, not like the thin tongues which leap themselves picturesquely round the devoted building, but broad, glaring, gleaming masses, which rose and floated like clouds of fire over the doomed wharves. From whatever point of view it was seen the spectacle...was grand and terrible – a mighty element in the full tide of its power, defying all the puny efforts of man. From the opposite side of the river it appeared like some volcano, throwing up its flames, reddening the sky, and illuminating all public buildings with the shade of an unnatural-looking autumnal sunset...the masts and flags and rigging of the ships in the river glowed as though they were in a red heat; the water reflected the towering flames of the burning ships, till the very Thames itself seemed on fire.

In truth, the very Thames itself not only seemed, but actually was, on fire. The tallow and oil from the burst barrels in the warehouses had poured out into the river, and the surface of the water was burning fiercely. Mr Hodges, the owner of a distillery near by, took it upon himself to act as fire-marshal until the arrival of the professionals of the London Fire Engine Establishment under their famous superintendent, James Braidwood. (For more on fires, see pp. 325–32.) Distilleries were dangerous places and often maintained their own private fire brigade, as did other manufacturers dealing with flammable goods, such as Price’s Candles (the company is still in Vauxhall today). Hodges brought out his two engines and was soon joined by another handful of private brigades. When the official fire brigade arrived, the groups worked together under Braidwood, as was customary. The London Fire Engine Establishment’s floating river-engine soon appeared, but it was almost low tide, and the water was not sufficiently deep for its pumps to operate. On the street side, too, the firefighters were

hampered. The same tallow and oil stores that had flowed into the river had also escaped into the street, where they were burning ankle deep. The firemen were forced back even further as the spice warehouses caught fire, the pepper-smoke blowing towards them in blinding clouds.

Fifteen miles away, Arthur Munby was on a train between Epsom and Cheam when he saw from the window ‘A pyramid of red flame on the horizon, sending up a column of smoke that rose high in the air & then spread...At New Cross [four miles away] the reflection of the firelight on houses & walls began to be visible; & as we drove along the arched way into town, the whole of Bermondsey was in a blaze of light.’

By now the warehouses of eight companies were ablaze, and clearly beyond rescue. The firemen went to work instead on drenching the surrounding streets and buildings, to prevent the fire spreading – but in vain. Their new engine, which pumped more strongly, via steam power rather than manual labour, was being repaired at a works in Blackfriars Road. Hodges went to retrieve it, returning with the steam engine and extra hose. Supervising this himself, he managed temporarily to prevent the fire from leaping to the next range of warehouses, as his men and the fire brigade were joined by members of the Royal Society for the Protection of Life from Fire, bringing their own engines.

Still the fire roared on. The floating engine on the river was almost engulfed: ‘the flames were so great, the explosions so frequent, the surface of the river being at the same period covered...with ignited tallow, and the flames rising 27 feet over the floating engine’ that it was forced to retreat to the Customs House Stairs on the far side of the river. For several hundred yards, the south bank of the Thames was on fire: burning barges floated across on burning water as the oil and tallow poured ‘in cascades’ from the wharfs.

Braidwood, the great hero, the man who had professionalized the service, was everywhere at once, advising, controlling, encouraging his brigade. At 7.30 he was seen by the wall of a warehouse behind Tooley Street, working out a plan and giving his exhausted men rations of brandy. Suddenly from behind the wall came a huge explosion of saltpetre. The wall burst outwards, and the last anyone saw of James Braidwood was as fifteen

feet of burning brickwork rained down on him and four or five others, burying them completely. ‘Any attempt to rescue, or even recover the body, or what might remain of it, was quite impossible.’ Instead, his men carried on as he had trained them.

Sometime after eleven o’clock that evening, the houses fronting Tooley Street caught fire. The fear was that a warehouse behind Cotton’s Warehouse would be engulfed: it was said to contain ‘several thousand barrels of tar’. By this time, ‘thousands’ of gallons of oil were on fire and pouring out in ‘liquid flames’. Each building that contained some form of fuel or fat – and there were many – was quickly set alight: ‘the flames rose high...in all sorts of colours – first there was a brilliant vermilion hue, which seemed to tip the pinnacles of the Tower of London, and the water side of the Custom-house’ across the river, then ‘the fire changed to a bright blue, and, at the same time, immense volumes of white and black smoke rolled over the house tops’.

The fire rapidly jumped over to granaries close to St Olave’s Church, near London Bridge. Behind the church, on the river, were moored ‘several schooners filled with barrels of oil, tar, and tallow’. Efforts had been made to tow them out to the middle of the river, but the steam tugs attempting this operation at low tide had themselves caught fire, ‘and in a short space of time were burnt down to the water’s edge’, while the cargoes of the schooners drifted ‘out blazing into the river...the blazing barrels of tar floating in a line along the banks of the river about a quarter of a mile in length and one hundred yards across...forming as it were a complete firing of flame twenty feet high’. At this point the wind shifted eastward, towards more tallow warehouses. By one in the morning the warehouses and shops in Tooley Street were given up for lost.

It was not until three o’clock, ten hours after the fire began, that it was finally contained in one area, although within that section buildings still burnt fiercely, punctuated by explosions as caches of saltpetre, gunpowder or sulphur were ignited. From St Olave’s Church to Battle Bridge Stairs, just under 1,000 feet from east to west, and from the Thames extending another 1,000 feet inland, to Tooley Street, the fire continued to burn: over eleven acres were completely razed.

And throughout these long hours, as the men, exhausted, grimy, choking, their leader dead, continued their struggle, sightseers arrived en masse. Only hours after the first flames had been seen, when it had become clear that this was a major fire, sellers of beer, ginger-beer, fruit, cakes and coffee crowded the streets, hoping to pick up extra trade when the pubs closed, although many pubs, seeing the number of spectators, stayed open all night.

As Munby’s train neared London, ‘Every head was thrust out of window,’ and at London Bridge he found ‘The station yard, which was as light as day, was crammed with people: railings, lamp posts, every high spot, was alive with climbers. Against the dark sky...the façade of S. Thomas’s Hospital and the tower of S. Saviour’s...both were fringed atop with lookers on.’ A few omnibuses were still waiting for passengers, and men fought for places, ‘offering three & four times the fare’, not to get away from the danger zone, but ‘for standing room on the roofs, to cross London Bridge’ and watch the fire. Munby was among them, ‘and we moved off towards the Bridge...with the greatest difficulty. The roadway was blocked up with omnibuses, whose passengers stood on the roofs in crowds; with cabs and hansoms, also loaded

outside

; with waggons pleasure vans & carts, brought out for the occasion and full of people; and amongst all these, struggling screaming & fighting for a view, was a dense illimitable crowd.’ Across the river, ‘every window and roof and tower top and standing space on ground or above, every vessel that hugged the Middlesex shore for fear of being burnt, & every inch of room on London Bridge was crowded with thousands upon thousands of excited faces, lit up by the heat. The river too, which shone like molten gold...was covered with little boats full of spectators, rowing up & down in the overwhelming light’, as watermen at the Customs House Stairs charged 1s to take people along the river, despite the great chunks of burning tallow choking the surface of the water.

It took Munby’s bus half an hour to inch its way across London Bridge. From nine in the evening until nearly dawn, ‘London-bridge and the approaches thereto presented all the appearance of the Epsom road on Derby day. Cabs were plying backwards and forwards on the bridge, carrying an unlimited number of passengers on the roof, at 6d per head. Omnibuses, licensed to carry 14 outside, were conveying double that number,’ while the

railway stations were so full of sightseers that passengers could neither reach nor leave their trains. On the north side of the Thames, ‘the Custom-house quay, Billingsgate Market, the various private quays, the Monument, the roof of the Coal Exchange, and every available place from which a sight could be had, was filled with people, and the strong reflection from the burning mass on the opposite side of the river on their eager and upturned faces, presented a most singular appearance to the spectator at a distance’. At 3 a.m., many ‘thousands...were still congregated on the bridge and in its neighbourhood’. The police had arrived to keep the crowds back, but as the numbers increased, they needed reinforcing with army regiments. Not only London Bridge, but also Waterloo and Westminster Bridges – in fact, any bridge from which even a glimpse of the fire could be caught – were thick with spectators.

Two hundred police continued on duty the next morning, as did the entire fire brigade. For days the fire continued to burst out at various points, walls still threatened to topple and explosions were constant as the heat of the smouldering fires found new barrels of explosives. On the 26th, four days after the fire began, ‘an immense body of fire suddenly shot up’ and took two hours to control. On the night of the 30th, engines were needed to pump water on new outbreaks. On 2 July, a full ten days after Scovell’s Warehouse first caught fire, leaseholders and owners were still stripping the surrounding buildings of goods and fittings, for fear that flare-ups might engulf them too. It was to be another ten days, one day short of three weeks, before the fire was finally judged to be contained, although even then large areas continued to smoulder.

Meanwhile, many were taking advantage of the fire’s largesse. Munby watched as ‘all the women and girls of the neighbourhood turned out with the boys and men, to gather the fat which floated in vast cakes down the river...For days and weeks it went on...many women & girls waded up to their necks in mud and water...Some too went up the great sewers hereabouts for the same purpose.’ Boat-owners were also busy collecting the valuable fats. ‘For days afterwards, as far afield as Erith’, twelve miles downriver, the ‘banks and mud flats were coated with grease’ assiduously gathered by ‘hordes of men, women and children’.

For months, the courts were bursting with people charged with stealing the salvaged fats, which, in the view of the magistrates, continued to belong to their original owners, despite having been dissipated along the river and down the sewers. One second-hand dealer was accused of buying more than a ton of this stolen fat. The fat’s legal owners, however, were more pragmatic, arranging salvage sales at knock-down prices for the mounds of tallow that blocked up the roads around Tooley Street: ‘the conditions of sale being an immediate clearance’.

Meanwhile, tourists continued to gather, from all levels of society. Two days after the outbreak of fire, ‘The burning ruins have been visited by the Earl of Stamford and lady, the Lord Mayor, and many other eminent gentlemen and their ladies,’ followed the next day by the Duke of Buccleuch, the Earl and Countess of Cardigan, Earl Spencer, Lord Alfred Paget and Lady Gower. Disraeli and his wife were initially barred when the policeman on duty failed to recognize him. It was a week before things began to return to normal. The gawpers on London Bridge thinned, forming a single line of spectators gazing at the devastated site, while the traffic once more ran smoothly as crowds no longer blocked the way, with no extra buses or cabs now driving back and forth at a walking pace to give the best views. Watermen, too, no longer found sightseers wanting to be rowed out, and the quays on the opposite shore were ‘comparatively free from intruders’.