The Undertaking (18 page)

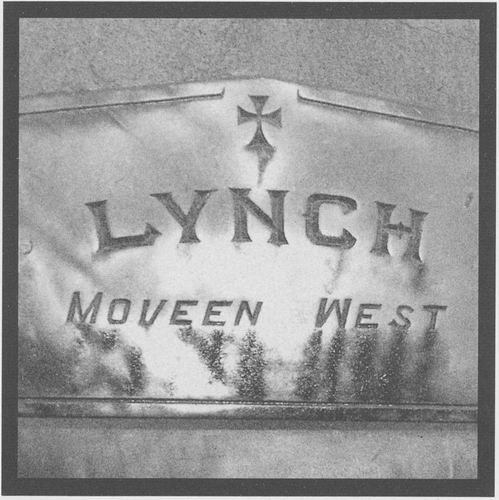

Authors: Thomas Lynch

I should probably fess up that we buy these caskets for less than we sell them for—a fact uncovered by one of our local TV news personalities, who called himself the News Hound, and

who was, apparently, untutored in the economic intrigues

of wholesale and retail. It was this same News Hound who did an expose on Girl Scout Cookie sales—how some of the money doesn’t go to the girls at all, but to the national office where it was used to pay the salaries of “staff.”

It was a well-worn trail the News Hound was sniffing—a trail blazed most profitably by Jessica Mitford who came

to the bestselling if not exactly original conclusion that the bereaved consumer is in a bad bargaining position. When you’ve got a dead body on your hands it’s hard to shop around. It’s hard to shop lawyers when you’re on the lam, or doctors when your appendix is inflamed. It’s not the kind of thing you let out to bids.

Lately there has been a great push toward “pre-arrangement.” Everyone who’s

anyone seems to approve. The funeral directors figure it’s money in the bank. The insurance people love it since most of the funding is done through insurance. The late Jessica, the former News Hound, the anti-extravagance crowd—they all reckon it is all for the best to make such decisions when heads are cool and hearts are unencumbered by grief and guilt. There’s this hopeful fantasy that by

prearranging the funeral, one might be able to pre-feel the feelings, you know, get a jump on the anger and the fear and the helplessness. It’s as modern as planned parenthood and prenuptial agreements and as useless, however tidy it may be about the finances, when it comes to the feelings involved.

And we are uniformly advised “not to be a burden to our children.” This is the other oft-cited

bonne raison

for making your final arrangements in advance—to spare them the horror and pain of having to do business with someone like me.

But if we are not to be a burden to our children, then to whom? The government? The church? The taxpayers? Whom? Were they not a burden to us—our children? And didn’t the management of that burden make us feel alive and loved and helpful and capable?

And

if the planning of a funeral is so horribly burdensome, so fraught with possible abuses and gloom, why should an

arthritic septuagenarian with blurred vision and some hearing loss be sent to the front to do battle with the undertaker instead of the forty-something heirs-apparent with their power suits and web browsers and cellular phones? Are they not far better outfitted to the task? Is it not

their inheritance we’re spending here? Are these not decisions they will be living with?

Maybe their parents do not trust them to do the job properly.

Maybe they shouldn’t.

Maybe they should.

T

he day I came to Milford, Russ Reader started pre-arranging his funeral. I was getting my hair cut when I first met him. He was a massive man still, in his fifties, six-foot-something and four hundred

pounds. He’d had, in his youth, a spectacular career playing college and professional football. His reputation had preceded him. He was a “character”—known in these parts for outrageous and libertine behavior. Like the Sunday he sold a Ford coupe off the used car lot uptown, taking a cash deposit of a thousand dollars and telling the poor customer to “come by in the morning when the office is

open” for the keys and paperwork. That Russ was not employed by the car dealer—a devout Methodist who kept holy his Sabbaths—did not come to light before the money had been spent on sirloins and cigars and round after round of drinks for the patrons of Ye Olde Hotel—visiting matrons from the Eastern Star, in town with their husbands for a regional confab. Or the time a neighbor’s yelping poodle—a

dog disliked by everyone in earshot—was found shot one afternoon during Russ’s nap time. The neighbor started screaming at one of Russ’s boys over the back fence, “When I get my hands on your father!” Awakened by the fracas, Russ appeared at the upstairs window and calmly promised, “I’ll be right down, Ben.” He came down in his paisley dressing gown, decked the neighbor with a swift left hook, instructed

his son to bury “that dead mutt,” and went back upstairs to finish his nap. Halloween was Russ’s favorite holiday, and he celebrated in more or less pre-Christian fashion, dressing himself up like a Celtic warrior, with an antlered helmet and mighty sword that, along with his ponderous bulk and black beard and booming voice, would scare the bejaysus out of the wee trick-or-treaters who nonetheless

were drawn to his porch by stories of full-sized candy bars sometimes wrapped in five-dollar bills. Russ Reader was, in all ways, bigger than life, so that the hyperbole that attended the gossip about him was like the talk of heros in the ancient Hibernian epics—Cuchulainn and Deirdre and Queen Maeve, who were given to warp-spasms, wild couplings, and wondrous appetites.

When he first confronted

me in the barber’s chair, he all but blotted out the sun behind him.

“You’re the new Digger O’Dell I take it.”

It was the black suit, the wing rips, the gray striped tie.

“Well, you’re never getting your mitts on my body!” he challenged.

The barber stepped back to busy himself among the talcums and clippers, uncertain of the direction the conversation might take.

I considered the size of

the man before me—the ponderous bulk of him, the breathtaking mass of him—and tried to imagine him horizontal and uncooperative. A sympathetic pain ran down my back. I winced.

“What makes you think I’d want anything to do with your body?” I countered in a tone that emphasized my indignation.

Russ and I were always friends after that.

He told me he intended to have his body donated to “medical

science.” He wanted to be given to the anatomy department of his alma mater, so that fledgling doctors could practice on him.

“Won’t cost my people a penny.”

When I told him they probably wouldn’t take him, on account of his size, he seemed utterly crestfallen. The supply of

cadavers for medical and dental schools in this land of plenty was shamefully but abundantly provided for by the homeless

and helpless, who were, for the most part, more “fit” than Russ was.

“But I was an all-American there!” Russ pleaded.

“Don’t take my word for it,” I advised. “Go ask for yourself.”

Months later I was watering impatiens around the funeral home when Russ screeched to a halt on Liberty Street.

“OK, listen. Just cremate me and have the ashes scattered over town from one of those hot-air balloons.”

I could see he had given this careful thought. “How much will it cost me, bottom line?”

I told him the fees for our minimum services—livery and paperwork and a box.

“I don’t want a casket,” he hollered from the front seat of his Cadillac, idling at curbside now.

I explained we wouldn’t be using a casket as such, still he would have to be

in

something. The crematory people wouldn’t accept his

body unless it was

in

something. They didn’t

handle

dead bodies without some kind of handles. This made tolerable sense to Russ. In my mind I was thinking of a shipping case—a kind of covered pallet compatible with fork-lifts and freight handlers—that would be sufficient to the task.

“I can only guess at what the balloon ride will cost, Russ. It’s likely to be the priciest part. And, of course,

you’d have to figure on inflation. Are you planning to do this very soon?”

“Don’t get cute with me, Digger,” he shouted. “Whadayasay? Can I count on you?”

I told him it wasn’t me he’d have to count on. He’d have to convince his wife and kids—the nine of them. They were the ones I’d be working for.

“But it’s

my

funeral!

My

money.”

Here is where I explained to Russ the subtle but important difference

between the “adjectival” and “possessive” applications

of the first-person singular pronoun for ownership—a difference measured by one’s last breath. I explained that it was really

theirs

to do—his survivors, his family. It was really, listen closely, “the heirs”—the money, the funeral, what was or wasn’t done with his body.

“I’ll pay you now,” he protested. “In cash—I’ll pre-arrange it all.

Put it in my Will. They’ll have to do it the way I want it.”

I encouraged Russ to ponder the worst-case scenario: his wife and his family take me to court. I come armed with his Last Will and pre-need documents insisting that his body get burned and tossed from a balloon hovering over the heart of town during Sidewalk Sale Days. His wife Mary, glistening with real tears, his seven beautiful daughters

with hankies in hand, his two fine sons, bearing up manfully, petition the court for permission to lay him out, have the preacher in, bury him up on the hill where they can visit his grave whenever the spirit moves them to.

“Who do you think wins that one, Russ? Go home and make your case with them.”

I don’t know if he ever had that conversation with them all. Maybe he just gave up. Maybe it

had all been for my consumption. I don’t know. That was years ago.

When Russ died last year in his easy chair, a cigar smoldering in the ashtray, one of those evening game shows flickering on the TV, his son came to my house to summon me. His wife and his daughters were weeping around him. His children’s children watched and listened. We brought the hearse and waited while each of the women kissed

him and left. We brought the stretcher in and, with his sons’ help, moved him from the chair, then out the door and to the funeral home where we embalmed him, gave him a clean shave, and laid him out, all of us amazed at how age and infirmity had reduced him so. He actually fit easily into a Batesville casket—I think it was cherry, I don’t remember.

But I remember how his vast heroics continued

to grow over two days of wake. The stories were told and told again. Folks wept and laughed outloud at his wild antics. And after the minister, a woman who’d known Russ all her life and had braved his stoop on Halloween, had had her say about God’s mercy and the size of Heaven, she invited some of us to share our stories about Russ. After that we followed a brass band, holding forth with “When

the Saints Go Marching In,” to the grave. And after everything had been said that could be said, and done that could be done, Mary and her daughters went home to the embraces of neighbors and the casseroles and condolences, and Russ’s sons remained to bury him. They took off their jackets, undid their ties, broke out a bottle and dark cigars and buried their father’s body in the ground that none of

us thought it would ever fit into. I gave the permit to the sexton and left them to it.

And though I know his body is buried there, something of Russ remains among us now. Whenever I see hot-air balloons—fat flaming birds adrift in the evening air—I sense his legendary excesses raining down on us, old friends and family—his blessed and elect—who duck our heads or raise our faces to the sky and

laugh or catch our breath or cry.

In even the best of caskets, it never all fits—all that we’d like to bury in them: the hurt and forgiveness, the anger and pain, the praise and thanksgiving, the emptiness and exaltations, the untidy feelings when someone dies. So I conduct this business very carefully because, in the years since I’ve been here, when someone dies, they never call Jessica or the

News Hound.

They call me.

Share with us

—

it will be money in your pockets. Go now I think you are ready.

—W

ILLIAM

C

ARLOS

W

ILLIAMS

, “T

RACT

”

I

’d rather it be February. Not that it will matter much to me. Not that I’m a stickler for details. But since you’re asking—February. The month I first became a father, the month my father died. Yes. Better even than November.

I want it cold. I want the gray to inhabit the

air like wood does trees: as an essence not a coincidence. And the hope for springtime, gardens, romance, dulled to a stump by the winter in Michigan.

Yes, February. With the cold behind and the cold before you and the darkness stubborn at the edges of the day. And a wind to make the cold more bitter. So that ever after it might be said, “It was a sad old day we did it after all.”

And a good

frosthold on the ground so that, for nights before it is dug, the sexton will have had to go up and put a fire down, under the hood that fits the space, to soften the topsoil for the backhoe’s toothy bucket.

Wake me. Let those who want to come and look. They have their reasons. You’ll have yours. And if someone says, “Doesn’t he look natural!” take no offense. They’ve got it right. For this was

always in my nature. It’s in yours.

And have the clergy take their part in it. Let them take their best shot. If they’re ever going to make sense to you, now’s the time. They’re looking, same as the rest of us. The questions are more instructive than the answers. Be wary of anyone who knows what to say.

As for music, suit yourselves. I’ll be out of earshot, stone deaf. A lot can be said for

pipers and tinwhistlers. But consider the difference between a funeral with a few tunes and a concert with a corpse down front. Avoid, for your own sakes, anything you’ve heard in the dentist’s office or the roller rink.

Poems might be said. I’ve had friends who were poets. Mind you, they tend to go on a bit. Especially around horizontal bodies. Sex and death are their principal studies. It is

here where the services of an experienced undertaker are most appreciated. Accustomed to being

personae non grata

, they’ll act the worthy editor and tell the bards when it’s time to put a sock in it.

On the subject of money: you get what you pay for. Deal with someone whose instincts you trust. If anyone tells you you haven’t spent enough, tell them to go piss up a rope. Tell the same thing to

anyone who says you spent too much. Tell them to go piss up a rope. It’s your money. Do what you want with it. But let me make one thing perfectly clear. You know the type who’s always saying “When I’m dead, save your money, spend it on something really useful, do me cheaply”? I’m not one of them. Never was. I’ve always thought that funerals were useful. So do what suits you. It is yours to do.

You’re entitled to wholesale on most of it.

As for guilt—it’s much overrated. Here are the facts in the case at hand: I’ve known the love of the ones who have loved me. And I’ve known that they’ve known that I’ve loved them,

too. Everything else, in the end, seems irrelevant. But if guilt is the thing, forgive yourself, forgive me. And if a little upgrade in the pomp and circumstance makes you

feel better, consider it money wisely spent. Compared to shrinks and pharmaceuticals, bartenders or homeopaths, geographical or ecclesiastical cures, even the priciest funeral is a bargain.

I

want a mess made in the snow so that the earth looks wounded, forced open, an unwilling participant. Forego the tent. Stand openly to the weather. Get the larger equipment out of sight. It’s a distraction.

But have the sexton, all dirt and indifference, remain at hand. He and the hearse driver can talk of poker or trade jokes in whispers and straight-face while the clergy tender final commendations. Those who lean on shovels and fill holes, like those who lean on custom and old prayers, are, each of them, experts in the one field.

And you should see it till the very end. Avoid the temptation of

tidy leavetaking in a room, a cemetery chapel, at the foot of the altar. None of that. Don’t dodge it because of the weather. We’ve fished and watched football in worse conditions. It won’t take long. Go to the hole in the ground. Stand over it. Look into it. Wonder. And be cold. But stay until it’s over. Until it is done.

On the subject of pallbearers—my darling sons, my fierce daughter, my

grandsons and granddaughters, if I’ve any. The larger muscles should be involved. The ones we use for the real burdens. If men and their muscles are better at lifting, women and theirs are better at bearing. This is a job for which both may be needed. So work together. It will lighten the load.

Look to my beloved for the best example. She has a mighty heart, a rich internal life, and powerful

medicines.

After the words are finished, lower it. Leave the ropes. Toss the gray gloves in on top. Push the dirt in and be done. Watch

each other’s ankles, stamp your feet in the cold, let your heads sink between your shoulders, keep looking down. That’s where what is happening is happening. And when you’re done, look up and leave. But not until you’re done.

So, if you opt for burning, stand

and watch. If you cannot watch it, perhaps you should reconsider. Stand in earshot of the sizzle and the pop. Try to get a whiff of the goings on. Warm your hands to the fire. This might be a good time for a song. Bury the ashes, cinders, and bones. The bits of the box that did not burn.

Put them in something.

Mark the spot.

Feed the hungry. It’s good form. Feed them well. This business works

up an appetite, like going to the seaside, walking the cliff road. After that, be sober.

T

his is none of my business. I won’t be there. But if you’re asking, here is free advice. You know the part where everybody is always saying that you should have a party now? How the dead guy always insisted he wanted everyone to have a good time and toss a few back and laugh and be happy? I’m not one of

them. I think the old teacher is right about this one. There

is

a time to dance. And it just may be this isn’t one of them. The dead can’t tell the living what to feel.

They used to have this year of mourning. Folks wore armbands, black clothes, played no music in the house. Black wreathes were hung at the front doors. The damaged were identified. For a full year you were allowed your grief—the

dreams and sleeplessness, the sadness, the rage. The weeping and giggling in all the wrong places. The catch in your breath at the sound of the name. After a year, you would be back to normal. “Time heals” is what was said to explain this. If not, of course, you were pronounced some version of “crazy” and in need of some professional help.

Whatever’s there to feel, feel it—the riddance, the relief,

the fright and freedom, the fear of forgetting, the dull ache of your own mortality. Go home in pairs. Warm to the flesh that warms you still. Get with someone you can trust with tears, with anger, and wonderment and utter silence. Get that part done—the sooner the better. The only way around these things is through them.

I know I shouldn’t be going on like this.

I’ve had this problem all my

life. Directing funerals.

It’s yours to do—my funeral—not mine. The death is yours to live with once I’m dead.

So here is a coupon good for Disregard. And here is another marked My Approval. Ignore, with my blessings, whatever I’ve said beyond Love One Another.

Live Forever.

A

ll I really wanted was a witness. To say I was. To say, daft as it still sounds, maybe I

am.

To say, if they ask

you, it was a sad day after all. It was a cold, gray day.

February.

O

f course, any other month you’re on your own. Have no fear—you’ll know what to do. Go now, I think you are ready.