The Undertaking (12 page)

Authors: Thomas Lynch

No doubt the impulse to do this—to get the dead to their own quarters was, at first, olfactory. The Neanderthal widow, waking to the dead lump of her man likely figured he was only being quiet or lazy. Was it something he’d eaten? Something she’d said? It might have been hours before she knew something was different. Here was a preoccupation or an indifference she’d never seen before. But not

until his flesh started rotting did the idea come to her to bury him because he’d been changed utterly and irretrievably and, if her nose could be trusted, not for the better. Thus the grave is first and foremost \\ a riddance. But this other impulse—to memorialize, to commemorate, to record has a more subtle motive. I think of Bishop Berkeley’s tree, requiring someone to hear it fall. We need our

witnesses and archivists to say we lived, we died, we made this difference. Where death means nothing, life is meaningless. It’s a grave arithmatic. The cairns and stone piles, the life stories drawn on cave walls, the monuments in graveyards, one and all, are the traces left of the species before us—a space that they’ve staked out in granite and bronze. And whether a pyramid or Taj Mahal, a great

vault in Highgate or a name on The Wall, we let them stand. We visit them. We trace the shapes of their names and dates with our fingers. We say the little epitaphs out loud. “Together forever.” “Gone but not forgotten.” We try to reassemble their lives from the stingy details, and the exercise teaches us something about how to live.

Is it kindness or wisdom, honor or self-interest?

We remember

because we want to be remembered.

M

ary Jackson can bring the dead to life. In reminiscences launched over luncheons or teas or walks through Oak Grove, she restores them to us. In her narratives, the dead become perfectly modern, given to the same fits of joy and sorrow as

ourselves. As when her Uncle Nick Stephens, in Mary’s childhood, came across a stone on the Crawford lot that read: “Behold

me now as you pass by. As you are now, so once was I. As I am now soon you will be. Prepare for death and follow me.” A good Victorian epitaph, memorable and morbid, a jingle in the stonemason’s best script. To which Uncle Nick, never at a loss for words, replied on the spot: “To follow you I won’t consent until I know which way you went.”

We buried Wilbur Johnson a few years back. He was put

in the grave at Oak Grove next to Milver and his name and dates carved into the stone. I see him striding up the steps of my office twenty-five years ago to ask if I was the new funeral director in town. “Well you’re a man I’ll need to know,” is what he said and then he said I could pick him up on the following Wednesday and drive him to the Chamber of Commerce luncheon. Wilbur always went more than

half way when it came to welcomes. And I can see him, in his last year, arm in arm with Mary Jackson in the ceremonial crossing of Oak Grove Bridge, the new bridge built by their determination, to cut the ribbon and open it to the general public. Bands were assembled, politicos, old soldiers from the VFW, the reverend clergy. It was a bright blue morning at the end of May—Memorial Day. Townspeople

gathered at the river to watch the festivities. A microphone had been rigged up with loudspeakers in the trees. Wilbur thanked all of the committee for their tireless efforts. The Village President said wasn’t it a fine thing. The state senator was pleased to have helped with a grant from the Department of Commerce and read off the names of people in Lansing. Then Mary read the poem I’d written

when it began to look like she’d actually get it built. And people stood among the stones and listened while Mary’s voice rose up over the river and mingled in the air with the echo of Catholic bells tolling and tunes in the Presbyterian steeple and the breeze with the first inkling of June in it working in the fresh buds of winter oaks. The fire whistle was silent. No dogs howled.

M

ary has

the gift of voices. When she speaks the words, she sounds like one of our own. And the words, when she says them, sound like hers and hers alone.

“At the Opening of Oak Grove Cemetery Bridge”

Before this bridge we took the long way around up First Street to Commerce, then left at Main, taking our black processions down through town among storefronts declaring

Dollar Days! Going Out of Business!

Final Mark Downs!

Then pausing for the light at Liberty, we’d make for the Southside by the Main Street bridge past used car sales and party stores as if the dead required one last shopping spree to finish their unfinished business. Then eastbound on Oakland by the jelly-works, the landfill site and unmarked railroad tracks—by bump and grinding motorcade we’d come to bury our dead by the river

at Oak Grove.And it is not so much that shoppers gawked or merchants carried on irreverently. As many bowed their heads or paused or crossed themselves against their own mortalities. It’s that bereavement is a cottage industry, a private enterprise that takes in trade long years of loving for long years of grief. The heart cuts bargains in a marketplace that opens after-hours when the stores

are dark and Christmases and Sundays when the hard currencies of void and absences nickel and dime us into nights awake with soured appetites and shaken faith and a numb hush fallen on the premises.Such stillness leaves us moving room by room rummaging through cupboards and the closetspace for any remembrance of our dead lovers, numbering our losses by the noise they made at home—in basements

tinkering with tools or in steamy bathrooms where they sang in the shower, in kitchens where they labored over stoves or gossiped over coffee with the nextdoor neighbor, in bedrooms where they made their tender moves; whenever we miss that division of labor whereby he washed, she dried; she dreams, he snores; he does the storm window, she does floors; she nods in the rocker, he dozes on the couch;

he hammers a thumbnail, she says Ouch!This bridge allows a residential route. So now we take our dead by tidy homes with fresh bedlinens hung in the backyards and lanky boys in driveways shooting hoops and gardens to turn and lawns for mowing and young girls sunning in their bright new bodies. First to Atlantic and down Mont-Eagle to the marshy north bank of the Huron where blue heron nest,

rock-bass and bluegill bed in the shallows and life goes on. And on the other side, the granite rows of Johnsons, Jacksons, Ruggles, Wilsons, Smiths—the common names we have in common with this place, this river and these winteroaks.And have, likewise in common, our own ends that bristle in us when we cross this bridge—the cancer or the cardiac arrest or lapse of caution that will do us in.

Among these stones we find the binding thread:

old wars, old famines, whole families killed by flues, a century and then some of our dead this bridge restores our easy access to. A river is a decent distance kept. A graveyard is an old agreement made between the living and the living who have died that says we keep their names and dates alive. This bridge connects our daily lives to them and makes

them, once our neighbors, neighbors once again.

Sweeney: Ah! Now the gallows trap has opened that drops the strongest to the ground! Lynchseachan: Sweeney, now you are in my hands, I can heal these father’s wounds: your family has fed no grave, all your people are alive.

S

EAMUS

H

EANEY

,

S

WEENEY

A

STRAY

M

y friend, the poet, Matthew Sweeney, is certain he is dying. This is a conviction he has held, without remission, since 1952 when

he first saw the light, in its gray Irish version, in Ballyliffin, in northernmost Donegal. He knew even then, though he was some years from the articulation of this intelligence, that something was very, very wrong.

What was it the pink infant Sweeney sensed, aswaddle in his bassinet, warmed by the gleeful cooing of his parents, a peacetime citizen of a green and peaceful place, that made him

conscious of impending doom?

Nor did his more or less idyllic childhood, his education at the Malin National School, his successful matriculation from the Franciscans at Gormanstown, nor his successful escape from university—first from Dublin, then from North London Polytechnic, and finally from Freiburg University (where he

befriended, for reasons soon to be illumined, a corps of medical students)—or

any of the several other blessing this life bestows, disabuse him of the sense, continuously a part of his psychology, that there was a deadly moment in every minute; an end with his name on it ever at hand.

Even after his successful wooing of the most beautiful woman in the neighboring parish, the former Rosemary Barber of Buncrana, praised in local song and story for the fierceness of her eyes,

the depth of her intellection, the lithe perfection of her form, and the sensibilities of character—even after such a triumph the niggling gloom that attended his conviction, far from going hush, grew louder still. For now he had not only a life to lose but a life made precious by the blissful consortium of married life. (A consortium on which his forthcoming collection

The Bridal Suite

will no

doubt shed inspired light.) In like manner, the birth of his daughter Nico, his heart’s needle if ever was, followed by the birth of his son Malvin, who soon enough would call him

Daddy

, made him immediately happier and accordingly sadder.

If you love your life in this world

, Matthew remembered Paul opining,

you will lose it.

He loved his life. What sane man wouldn’t. Loss, he figured, stalked

him with its scythe.

H

e’d written poems. He liked the sound of words of his own making in his own mouth. He’d met with early and deserved critical success. The Sweeneys had long since settled in London, the better to pursue his literary career. The better, likewise, for a man whose fear of driving was, by his own admission, consummate—a dread driven by visions of his body and the bodies of

his children entangled with metal to their disadvantage. London, with its Underground, buses, and reliable taxi hacks, unlike the hinterlands of Donegal, gave Matthew the mobility he needed without the morbidity risked by driving a car. What’s more, the Kingdom’s capital is

one of the great ambulatories of the world, providing access, at every turn, to the retail purveyors of essential and elective

goods.

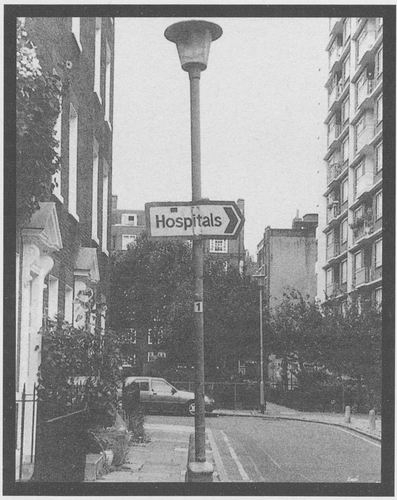

Thus, from the stoop of his ample flat in Dombey Street, Matthew Sweeney need only travel eastward less than two hundred meters whereupon he finds himself in Lambs Conduit Street—a walking mall of small shops and markets. Within a stone’s throw of his premises is a pharmacist (to whom Mr. Sweeney addresses frequent queries), a French bakery for croissants, a florist (from whom Mr. Sweeney

purchased the wee cacti that became the title poem of his most recent and acclaimed collection), his local public house, The Lamb (for the usual wetgoods), a dry cleaners, two coffee shops, a grocery and a greengrocer (with whom Mr. Sweeney has long debated the use and abuses of diverse lettuces, aubergine, and chili peppers), two victualers (one Irish, one Prussian), an herbalist (on whose custom

I am unqualified to comment), and the Bloomsbury office of A. France Undertakers—one of London’s eldest and most respected carriage-trade mortuaries, passing by whose black and gilded storefront, Mr. Sweeney can be observed to quicken his pace and heard to whistle the fragments of a Tom Waits tune. Only the loss, in 1991, of Bernard Stone’s Turret Bookshop (which housed the city’s most comprehensive

selection of contemporary poetry along with Bernard Stone himself) diminished the hospitable cityscape outside the Sweeneys’ door.

One block due north of which, it is worthy of notice, stands the ancient and imposing structure of The Royal London Homeopathic Hospital. No one of the hundreds of poets and writers who have made their pilgrimage to Matthew’s home regards this proximity as happenstance.

But whether the availability of emergency care or the endless parade of distressed humanity within eyeshot of his fourth-floor living room adds to or subtracts from Matthew’s angst is anyone’s guess. Maybe Sweeney himself doesn’t know. But his frequent foot travels

west into Queen’s Square to meet with his man at Faber & Faber, the publisher of Matthew’s children’s poems (whose appeal, according

to reviewers, proceeds from their dark homage to monsters and menace and the inherent dangers of maturation), take him, inevitably, by the hospital’s massive edifice.

Indeed, the Sweeney home in Bloomsbury (a place name from which a wordsmith of Matthew’s caliber can easily extract the vital and the morbid etymological strains) sits at an epicenter of the medical forces, to wit: the Royal College

of Surgeons, the London University Hospital, the Society of Endocrinologists, Her Majesty’s Hospital for Neurological Disease, the Hospital for Tropical Diseases (where Matthew once left samples of urine and sputum to be screened for the Ebola virus), which, along with other regiments of the medical militia, all within walking distance, speak to the battle being endlessly waged between man (in

the gender inclusive sense) and the microbial forces of nature by which he (see above) is infested, infected, afflicted, endangered, diseased, and ultimately—and this is Matthew’s point—put to death.

P

erhaps a little history here. It was in Bewley’s Museum over Grafton Street where I first met Matthew Sweeney. It was Dublin and springtime of 1989. The Irish launch of his fourth collection,

Blue Shoes

, occurred but the day before a reading I was giving in the upper room of the famous coffee emporium. He prevailed upon his editor, now our editor, to stay in Dublin an extra day so the two of them might come to my reading. One of our Dublin friends in common, Philip Casey, the poet and novelist, had given me Matthew’s poems and given Matthew some of mine. There followed a genial correspondence

on themes of admiration and shared acquaintance that prefaced our meeting face to face. We repaired to Grogan’s Bar according to the local custom. I was touched by

his generous praise for my reading, by his interest in my occupational familiarity with the grisly dimensions of disease and pathology, and by his apparent preference for black attire, a preference I share of practical necessity.

The audience was too brief, the barroom too noisy, I was jetlagged, and Matthew, not fully recovered from the night before. Happily, it was the first of many meetings since, in England and in Ireland and in Michigan, where each of us has enjoyed the comforts of the other’s home, the company of the other’s wife, the wonderments of the other’s children, and the society of the other’s friends. To which

abundance must be added the dialogue of each other’s poems, in which reviewers have found different treatment of similar themes—of domestic perils, imminent damage, and the transcendent properties of death.

A

mong the society of writers and foodies (about which, more anon) he keeps in London, Matthew is fashioned a charming neurotic of the hypochondriacal variety. There are accounts of his inflation

of the common cold to pneumonia or tuberculosis. His headaches are all brain tumors; his fevers, meningitis; his hangovers, all peptic ulcers or diverticulitis. Any deviations from the schedule of his toilet are bowel obstructions or colon cancer. He has been tested for every known irregularity except pregnancy, though he takes, on a seasonal basis, medication for PMS from which, no one doubts,

he suffers. He is a consumer of medical opinion and keeps a list of specialists and their beeper numbers on his person. A cardiologist, an acupuncturist, an immunologist, an oral surgeon, an oncologist, a proctologist, and a behavioral psychologist join several psychic and holistic healers from regional and para-religious persuasions to make up Matthew’s medical retinue. The same numbers are

programmed on speed-dial from his home phone. And where most of his co-religionists wear a medallion that reads

In Case of Emergency Call a Priest

,

Sweeney’s reads

Call an Ambulance. Call a Doctor. Please Observe Universal Precautions.

He has consulted for or imagined having every known malady of the human species from Albers-Schönberg disease to Zygomycosis infection and seems strangely uplifted

by the transmigration of ailments between genus and sub-groups heretofore unknown. Thus, swine flu, deer tick disease, feline leukemia, brown bat rabies, and, of course, parrot fever must be ruled out at his quarterly physical exams.

He is, and will suffer no quarrel on this account, the only known survivor of mad cow disease, caught, he insists, from the meagre-most portion of tenderloin that

accompanied kippers and poached eggs at Simpsons-on-the-Strand, where he brunched, by appointment, with the restaurant reviewer for the London

Observer.

Their discussion of mushrooms in Southern French cuisine apparently filled Matthew with such overwhelming images of toxicity that the paramedics had to be called.

The standing joke is that Matthew possesses an open offer of a sizable advance

from a prominent publisher for an intimate treatise on hypochondria, which, alas, he has never felt well enough to do.

But while others nod and wink and roll their eyes, I have come to wonder if he isn’t a harbinger, a kind of visionary, a prophet, a voice crying out in the urban desert,

The End Is Near, It’s Later than You Think.

I

t was not only the commuter services or the literary milieu

or the world-class health care that brought Sweeney to London. It was the food. Unimaginative about the preparation of food, the British have brought the best from the far reaches of the former Empire to London. There is no regional or national or ethnic cuisine on the face of the planet that does not have an office in London. And Matthew has made it his mission to sample and to savor and to study

each. He is a student of the palate and the

plate, a sage of the taste buds, tongue, and tablefare. In this incarnation he has found the best Thai eatery (Tui in South Kensington, near the offices of Secker & Warburg), the best Afghan (The Caravan Serai in Paddington Street), the best Indian (The Red Fort in Soho), the finest dim-sum (Harbor City in Chinatown), the ultimate noodle-bar (Wagamama

in Streathern Street behind the British Museum), the most reliable vegetarian curry (Mandeer in an alleyway behind Tottenham Court Road Station). The geography of taste is as boundless for a man as the sky is borderless to flighted birds. And Sweeney often seems—rapt in sampling some hitherto unknown morsel—almost winged with delight, a rare bird of an urban paradise.

But where the goldfinch

craves thistle and the pelican, fish, and the hummingbird, nectar, and the peregrine, meat; the free-range of Matthew’s hankerings is suited to the city’s cosmopolitan menu and he plots his daily flights according to a constellation of favorites that shine brightly in his firmament of food. On these crusades he is often accompanied by willing accomplices from the arts of verse or gourmandery for whom

a meal shared with Matthew Sweeney is a tuition they are more than happy to pay. (Here, as elsewhere, the temptation to drop names, well known in the world of letters and epicures, is nearly unavoidable. But I was better raised than that. To err by silence is better than omission.)