The Sword And The Olive (44 page)

Read The Sword And The Olive Online

Authors: Martin van Creveld

MAP 13.1 THE 1973 WAR, EGYPTIAN FRONT

During the afternoon the plan was worked out in a meeting among Elazar, Gonen, and Adan (Sharon arrived late and had to be briefed separately).

37

The dominant factor was the IDF’s lack of reserves: Between the canal and Tel Aviv there were no more than three divisions. Accordingly, instead of attacking with all forces united as classical armored doctrine would dictate, it was decided to proceed in echelon. While Mandler stood by, Adan was to attack early in the morning while Sharon joined later. Adan himself was not to attack from east to west, as Gonen’s regular brigades had the previous day; instead he was to proceed north to south, rolling up the Egyptians but staying two miles away from the earthen ramp on the west side of the canal, which was “swarming with [Egyptian] infantry equipped with antitank weapons.” Still, he was to rescue as many of the remaining

meozim

as possible. Arriving near the area known as Chamutal, about midway down the canal and just north of the Great Bitter Lake, he was to link up with Sharon. Together the two divisions were to effect a crossing.

37

The dominant factor was the IDF’s lack of reserves: Between the canal and Tel Aviv there were no more than three divisions. Accordingly, instead of attacking with all forces united as classical armored doctrine would dictate, it was decided to proceed in echelon. While Mandler stood by, Adan was to attack early in the morning while Sharon joined later. Adan himself was not to attack from east to west, as Gonen’s regular brigades had the previous day; instead he was to proceed north to south, rolling up the Egyptians but staying two miles away from the earthen ramp on the west side of the canal, which was “swarming with [Egyptian] infantry equipped with antitank weapons.” Still, he was to rescue as many of the remaining

meozim

as possible. Arriving near the area known as Chamutal, about midway down the canal and just north of the Great Bitter Lake, he was to link up with Sharon. Together the two divisions were to effect a crossing.

How Adan could expect to stay out of range

and

rescue the

meozim

—let alone expect to cross the canal—remains a mystery. The plan was not clarified despite a series of conversations that took place that night; Dayan, Elazar, Tal (Elazar’s deputy), Gonen, Magen (Gonen’s deputy), Adan, and Sharon all contributed to increase the confusion by suggesting various alternatives and corrections.

38

In the end, the only clear directive came from Elazar, who felt a lively distrust of his “wild” subordinates, Gonen and Sharon, and forbade a canal crossing without his prior permission. As we shall presently see, even that directive was destined to be violated, though admittedly only thanks to the overheated imagination of a junior IDF officer who was listening to the communications network.

and

rescue the

meozim

—let alone expect to cross the canal—remains a mystery. The plan was not clarified despite a series of conversations that took place that night; Dayan, Elazar, Tal (Elazar’s deputy), Gonen, Magen (Gonen’s deputy), Adan, and Sharon all contributed to increase the confusion by suggesting various alternatives and corrections.

38

In the end, the only clear directive came from Elazar, who felt a lively distrust of his “wild” subordinates, Gonen and Sharon, and forbade a canal crossing without his prior permission. As we shall presently see, even that directive was destined to be violated, though admittedly only thanks to the overheated imagination of a junior IDF officer who was listening to the communications network.

At 0800 hours on October 8, Adan, supported by exactly four artillery barrels instead of the several dozen he should have had and receiving only a small fraction of the air support promised,

39

started his advance from the area around Kantara. His men were farther away from the canal than they believed, however, and consequently made very good progress while meeting hardly any Egyptians. Arriving opposite Chamutal as agreed, they found the last of Sharon’s forces about to move away to the south—having been ordered to do so by Gonen for reasons that remain unclear today.

40

Nevertheless Adan’s division performed its right turn and charged west toward the canal. Ordered not to cross without permission, Gonen, Adan, and Col. Natan Nir—who commanded Adan’s leading brigade—all took care to stay in the rear so they might stay in contact with superiors despite Egyptian interference with the radio network. Somehow rumor spread that a crossing had taken place—which, if true, would have been a violation of orders. While the chief of staff, in the middle of a Cabinet meeting, tried to find out what was going on, his subordinates “down south” lost control of their forces. Of the two battalions that attacked separately (instead of together, as armored doctrine would have dictated), the first was thrown back with heavy losses. The second was all but annihilated; its commander, along with many of his men, was captured.

41

39

started his advance from the area around Kantara. His men were farther away from the canal than they believed, however, and consequently made very good progress while meeting hardly any Egyptians. Arriving opposite Chamutal as agreed, they found the last of Sharon’s forces about to move away to the south—having been ordered to do so by Gonen for reasons that remain unclear today.

40

Nevertheless Adan’s division performed its right turn and charged west toward the canal. Ordered not to cross without permission, Gonen, Adan, and Col. Natan Nir—who commanded Adan’s leading brigade—all took care to stay in the rear so they might stay in contact with superiors despite Egyptian interference with the radio network. Somehow rumor spread that a crossing had taken place—which, if true, would have been a violation of orders. While the chief of staff, in the middle of a Cabinet meeting, tried to find out what was going on, his subordinates “down south” lost control of their forces. Of the two battalions that attacked separately (instead of together, as armored doctrine would have dictated), the first was thrown back with heavy losses. The second was all but annihilated; its commander, along with many of his men, was captured.

41

Up until then Elazar and the rest, grossly underestimating the Egyptians (there was talk of “waving” them across the canal), had expected to win the war with comparative ease. The failure of the first counteroffensive plunged GHQ into gloom, however, and that evening a stunned public listened to Brigadier General (ret.) Yariv, the former intelligence chief, explain on radio and TV that this was a war and not a picnic. The defeat of October 8 was not the last. Having wasted the afternoon driving south in pursuit of some imaginary “disaster” that never took place,

42

Sharon’s division returned to the area that evening. On the morning of October 9 one of his brigades tried its luck against Chamutal but met with the usual hail of antitank missiles and was repulsed with losses.

43

42

Sharon’s division returned to the area that evening. On the morning of October 9 one of his brigades tried its luck against Chamutal but met with the usual hail of antitank missiles and was repulsed with losses.

43

On the positive side, that evening Sharon’s reconnaissance battalion was able to locate the seam between Egypt’s 3rd and 2nd Armies.

44

Driving into it, it reached the canal just north of the Greater Bitter Lake without firing a shot. His tactical instincts aroused—he had always believed in taking the enemy from the rear—Sharon called Elazar’s deputy, Tal, and requested permission to cross.

45

However, GHQ had been chastened by the previous day’s experience and wanted to wait until after the Egyptians had committed their armored reserves to the east bank. On the next day a frustrated Elazar sent out General Bar Lev to take charge of the southern front from Gonen, leaving the latter in place but reducing him to a figurehead.

46

With that the Egyptian front calmed down for a few days as events on the Golan took priority.

44

Driving into it, it reached the canal just north of the Greater Bitter Lake without firing a shot. His tactical instincts aroused—he had always believed in taking the enemy from the rear—Sharon called Elazar’s deputy, Tal, and requested permission to cross.

45

However, GHQ had been chastened by the previous day’s experience and wanted to wait until after the Egyptians had committed their armored reserves to the east bank. On the next day a frustrated Elazar sent out General Bar Lev to take charge of the southern front from Gonen, leaving the latter in place but reducing him to a figurehead.

46

With that the Egyptian front calmed down for a few days as events on the Golan took priority.

Although hampered by its decision to defend the

meozim

, the IDF in the Sinai possessed considerable room for strategic maneuver. This was much less true on the Golan Heights, which are nowhere more than twenty miles wide. Here, too, a chain of fifteen strongholds had been constructed along the purple (cease-fire) line. In the event the most important stronghold, located on Mount Chermon and containing a variety of electronic sensors, was captured during the first hours by Syrian commandos who arrived by helicopter. The rest were bypassed and, though none of them fell, played no further role in the war (see Map 13.2).

meozim

, the IDF in the Sinai possessed considerable room for strategic maneuver. This was much less true on the Golan Heights, which are nowhere more than twenty miles wide. Here, too, a chain of fifteen strongholds had been constructed along the purple (cease-fire) line. In the event the most important stronghold, located on Mount Chermon and containing a variety of electronic sensors, was captured during the first hours by Syrian commandos who arrived by helicopter. The rest were bypassed and, though none of them fell, played no further role in the war (see Map 13.2).

To defend against the three-division Syrian attack the IDF initially deployed just one armored brigade, the “Barak Brigade.” Whether because of its previous experience or because of some misunderstanding with the CIC Northern Command, Barak’s commander, Col. Benyamin Shoham, initially assumed that the “war” about which he had been warned that morning was just another border clash.

47

Accordingly, instead of keeping his forces together for a counterattack, he sent them forward to their dispersed firing positions all along the line. During the afternoon he was reinforced by 7th Armored Brigade, previously standing in reserve but now moved to take over the northern sector. This move came too late to save the Barak, whose tanks had come under antitank missile fire and then were bypassed by the advancing enemy columns (unlike the Syrians, the Israelis did not have proper night-fighting equipment). By the afternoon of October 7 Shoham had been killed and his brigade all but annihilated.

47

Accordingly, instead of keeping his forces together for a counterattack, he sent them forward to their dispersed firing positions all along the line. During the afternoon he was reinforced by 7th Armored Brigade, previously standing in reserve but now moved to take over the northern sector. This move came too late to save the Barak, whose tanks had come under antitank missile fire and then were bypassed by the advancing enemy columns (unlike the Syrians, the Israelis did not have proper night-fighting equipment). By the afternoon of October 7 Shoham had been killed and his brigade all but annihilated.

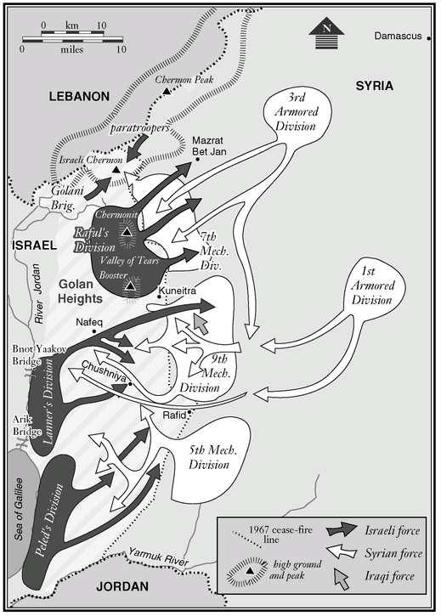

MAP 13.2 THE 1973 WAR, SYRIAN FRONT

With 7th Armored Brigade now opposing it in the north, the Syrian offensive was most successful in the south. On the morning of October 7 the Syrians recognized this fact, sending in the armored division standing in reserve for precisely that eventuality. Advancing under a heavy artillery barrage it drove on Nafeq, where the Israeli forces on the Golan had their headquarters, forcing their commander—Major General Eytan—to evacuate.

48

By afternoon the only force facing the Syrians was the IAF, its Skyhawks heroically throwing themselves at the enemy and being shot down in significant numbers.

49

CO Northern Command, Gen. Yitschak Choffi, had left the Golan Heights during the afternoon of October 6; now he ordered that the Jordan bridges be prepared for demolition.

50

At that point the first reserve units began to arrive. They belonged to a division under Maj. Gen. Moshe Peled that had previously been facing Jordan. Relations with King Hussein, however, were tolerably good, and Elazar was gambling that he would not intervene.

51

This enabled Peled to make his way to the southern part of the Golan Heights, and by morning on October 8 he took over the main burden of the defense in that sector.

48

By afternoon the only force facing the Syrians was the IAF, its Skyhawks heroically throwing themselves at the enemy and being shot down in significant numbers.

49

CO Northern Command, Gen. Yitschak Choffi, had left the Golan Heights during the afternoon of October 6; now he ordered that the Jordan bridges be prepared for demolition.

50

At that point the first reserve units began to arrive. They belonged to a division under Maj. Gen. Moshe Peled that had previously been facing Jordan. Relations with King Hussein, however, were tolerably good, and Elazar was gambling that he would not intervene.

51

This enabled Peled to make his way to the southern part of the Golan Heights, and by morning on October 8 he took over the main burden of the defense in that sector.

Meanwhile Eytan’s other brigade, 7th Armored, was fighting for its life in the north. Its men, though highly trained, were untested in combat; carefully maneuvering their fifty-ton Centurions to skirt the irrigation pipes that laced the terrain, they took up positions. Minutes later they found themselves fighting for their lives as tungsten bolts smashed into them in a hail of artillery fire. Col. Avigdor Ben Gal’s men had the advantage of the terrain, which slopes gently downward from west to east, enabling them to bear down with their guns on the advancing Syrians. Still, as they came under attack by two divisions, by the evening of October 8 the situation looked bad enough—the more so because they did not have night-vision equipment and on occasion were reduced to silencing their engines to discover who was who in the dark.

52

52

On the morning of October 9 the situation of 7th Armored Brigade became desperate when the Syrians committed their other reserve armored division in an effort to break through to the Jordan bridges. Unlike the remaining Syrian forces this division was equipped with T-62 tanks, the most powerful in the Arab arsenal and the only ones with guns matching the Israeli 105mm guns. As the Syrians also started landing commandos in the Israeli rear, around noon that day everything appeared to be lost. In particular, the tanks of one battalion—Col. Avigdor Kahalani’s 77th—were down to their last few rounds of ammunition and being pushed back step by step toward the escarpment in their rear.

53

Then suddenly the Syrian rear echelons turned around and retreated, followed by the tanks in the forward line.

53

Then suddenly the Syrian rear echelons turned around and retreated, followed by the tanks in the forward line.

The reasons for the Syrian retreat, which, judging from the way it proceeded, must have been ordered from above, have never been made clear. It could be that their forces were being threatened on their left (south) flank, but even the Israelis seem unable to agree as to which of their units could have been responsible for the critical move. One source identifies an improvised task force numbering fifteen tanks from the defeated Barak Brigade; another identifies the advance units of a second reserve division under Maj. Gen. Dan Lanner that had climbed up the center of the Golan Heights and was turning north.

54

In view of this confusion, a second and perhaps more credible explanation is that Israel, which on the evening of October 8 felt that the battle was being lost, had threatened Syria by rattling its nuclear saber (or so claimed a

Time

story published several years after these events).

55

54

In view of this confusion, a second and perhaps more credible explanation is that Israel, which on the evening of October 8 felt that the battle was being lost, had threatened Syria by rattling its nuclear saber (or so claimed a

Time

story published several years after these events).

55

Whatever the reason for the decision, from this point on, the situation was stabilized. In the north the enemy in front of 7th Armored Brigade melted away, leaving the so-called Valley of Tears strewn with hundreds of burned-out tanks and combat vehicles. Farther south, the two divisions that had formed part of the Syrian left-wing drive were caught between Peled driving along the purple cease-fire line and Lanner. Once they had been annihilated—which took place on October 9 and 10—the time had come to mount a counterattack. It started on October 11 and consisted of 7th Armored Brigade, the three brigades of Lanner’s division, and an additional brigade transferred from Peled.

Before the war the IDF’s planning branch under Brig. Gen. Avraham Tamir had warned that the Arabs possessed thousands of antitank missiles.

56

Yet somehow the significance of this fact had failed to sink in, leading to the futile counterattacks of the first few days. Now, however, the Israelis proved able to learn from experience—perhaps their single greatest advantage in the entire war. No longer did the tanks charge on their own; instead they moved inside an artillery “box” formed by thousands of exploding shells while they and their accompanying APCs raked every rock capable of offering shelter with machine-gun fire. Early on October 13 they met a thrust by the advance brigade of a 60,000-man Iraqi expeditionary force. Coming from the south, the brigade’s tanks were driving with their hatches closed when they entered a killing ground and were all but annihilated by Lanner’s tanks.

57

Still, this distraction, plus fierce Syrian resistance, sufficed to slow down the advance until it petered out twenty miles short of Damascus.

56

Yet somehow the significance of this fact had failed to sink in, leading to the futile counterattacks of the first few days. Now, however, the Israelis proved able to learn from experience—perhaps their single greatest advantage in the entire war. No longer did the tanks charge on their own; instead they moved inside an artillery “box” formed by thousands of exploding shells while they and their accompanying APCs raked every rock capable of offering shelter with machine-gun fire. Early on October 13 they met a thrust by the advance brigade of a 60,000-man Iraqi expeditionary force. Coming from the south, the brigade’s tanks were driving with their hatches closed when they entered a killing ground and were all but annihilated by Lanner’s tanks.

57

Still, this distraction, plus fierce Syrian resistance, sufficed to slow down the advance until it petered out twenty miles short of Damascus.

Other books

Snow Like Ashes by Sara Raasch

Faith’s Temptation (Dueling Dragons MC Book 1) by Angie Sakai

War Horse by Michael Morpurgo

PMadriani 12.5 - The Second Man by Martini, Steve

Jason's Princess: A King Brothers Story by Elise Manion

The Company of Shadows (Wellington Undead Book 3) by Richard Estep

Ten Years On by Alice Peterson

If Books Could Kill by Carlisle, Kate

When the Morning Glory Blooms by Cynthia Ruchti

Soul Deep by Leigh, Lora