The Sword And The Olive (47 page)

Read The Sword And The Olive Online

Authors: Martin van Creveld

More seriously, the months immediately after the war saw pressure build for an investigation. The government, which at first tried to resist, was forced to give in. A commission of inquiry was put together with the state comptroller and two former chiefs of staff (Yadin and Laskov) as its members; its chairman was High Court Justice Shimon Agranat, and the fifth member also a High Court justice. The commission was given a mandate to examine the events that led to the war as well as the first three days of operations. In its report it subjected the IDF to scathing criticism, including the failure to build up sufficient stores and to properly maintain those available. The chief of intelligence, the CO Southern Command, and the chief of staff were pilloried: the first for having failed to serve advance warning; the second for his conduct of operations during the first three critical days; and the third for having failed to order mobilization in good time. All three were forced to resign, and Elazar died soon after. Much to the former chief of staff’s chagrin, the commission exonerated Dayan, who thereby gave one last display of his knack for avoiding responsibility. However, the former national idol was crucified by public opinion. When Ms. Meir resigned in April and was replaced by Yitschak Rabin, Dayan was left out of the government.

Meanwhile, even as the “First Separation of Forces Agreement” was signed with Egypt in January 1974, the work of reconstruction got under way. At first sight it was highly successful; as we shall see, a combination of massive U.S. aid (financial and technological), plus the mobilization of Israeli resources to an extent never previously attained in peacetime, resulted in the creation of a true juggernaut not only in regional terms but even on a worldwide scale. This army was still capable of spectacular feats, such as the Entebbe raid in 1976 and the bombing of the Iraqi nuclear reactor in 1981. When it invaded Lebanon in June 1982 its early victories—especially those of the IAF over Syria’s air force and antiaircraft defenses—astonished the world.

Yet something of the earlier enthusiasm was gone. Particularly in the years immediately following 1967, war had been regarded almost as a lighthearted adventure in which heroic Israeli tankmen crashed into (

nichnesu be

-, Israeli slang meaning, literally, “entered”) second-rate opponents while they themselves were “exposed in the turret.” In 1973 many tankmen had been killed and others suffered horrible burns, however, causing the tanks’ hatches to be closed tight. All at once, war ceased to be a glamorous occasion honored by popular songs; instead it became a bloody, serious business in which many people were killed and others mutilated, wounded, and bereaved. Over time, graffiti reading

kol ha-kavod le-

TSAHAL (doff your hat to TSAHAL) tended to disappear from the streets. In 1978 Prime Minister Begin tried to turn back the clock by proposing to hold a military parade on Independence Day with himself on the stand and taking the salute; however, neither the public nor the IDF were enthusiastic, and the idea had to be dropped. To substitute for the departed glamour, “strategy” in its Western, intellectual, and instrumental sense invaded Israel, which hitherto had been remarkably free of it. Israel still had no “defense community” to speak of—the IDF being much too proud to take outside advice—so the Center of Strategic Studies was opened as an affiliate of Tel Aviv University, and over the years has done useful if not spectacular work. Books and monographs on the subject multiplied, as did professors who researched and taught it.

nichnesu be

-, Israeli slang meaning, literally, “entered”) second-rate opponents while they themselves were “exposed in the turret.” In 1973 many tankmen had been killed and others suffered horrible burns, however, causing the tanks’ hatches to be closed tight. All at once, war ceased to be a glamorous occasion honored by popular songs; instead it became a bloody, serious business in which many people were killed and others mutilated, wounded, and bereaved. Over time, graffiti reading

kol ha-kavod le-

TSAHAL (doff your hat to TSAHAL) tended to disappear from the streets. In 1978 Prime Minister Begin tried to turn back the clock by proposing to hold a military parade on Independence Day with himself on the stand and taking the salute; however, neither the public nor the IDF were enthusiastic, and the idea had to be dropped. To substitute for the departed glamour, “strategy” in its Western, intellectual, and instrumental sense invaded Israel, which hitherto had been remarkably free of it. Israel still had no “defense community” to speak of—the IDF being much too proud to take outside advice—so the Center of Strategic Studies was opened as an affiliate of Tel Aviv University, and over the years has done useful if not spectacular work. Books and monographs on the subject multiplied, as did professors who researched and taught it.

Except during moments when they got carried away, the leaders of Israel’s defense establishment had always been well aware of the country’s inability to achieve final victory by breaking the will of the Arab countries and forcing them to make peace.

1

Now, even as the IDF grew more and more powerful, the limits of its power were demonstrated time and again—against progressively weaker opponents, no less. First in Lebanon and then during the Palestinian uprising it failed to perform as well as expected. In between it showed that it could not protect Israel against missile attack and was made to stand idly by as others smashed Saddam Hussein’s war machine. Even as its size peaked during the mid-1980s, it was becoming bloated and top-heavy. By the end of the decade the IDF’s morale was beginning to decline; by the mid-1990s it was clearly in a bad way. In some important respects it was as if the story of the U.S. armed forces in Vietnam was being reenacted, with the ominous difference that Israel is a mere speck on the map and does not have the Pacific Ocean to separate it from its Arab and, above all, Palestinian opponents.

1

Now, even as the IDF grew more and more powerful, the limits of its power were demonstrated time and again—against progressively weaker opponents, no less. First in Lebanon and then during the Palestinian uprising it failed to perform as well as expected. In between it showed that it could not protect Israel against missile attack and was made to stand idly by as others smashed Saddam Hussein’s war machine. Even as its size peaked during the mid-1980s, it was becoming bloated and top-heavy. By the end of the decade the IDF’s morale was beginning to decline; by the mid-1990s it was clearly in a bad way. In some important respects it was as if the story of the U.S. armed forces in Vietnam was being reenacted, with the ominous difference that Israel is a mere speck on the map and does not have the Pacific Ocean to separate it from its Arab and, above all, Palestinian opponents.

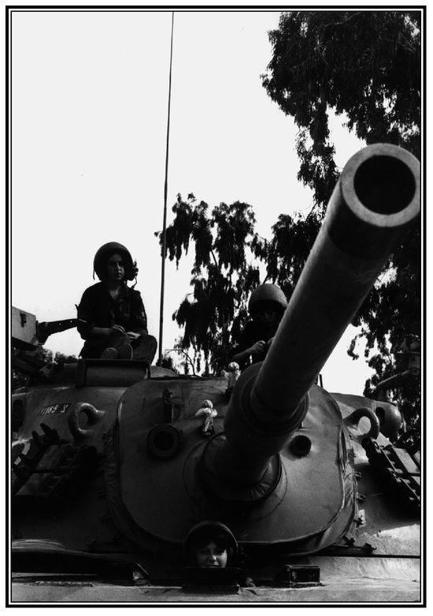

Recovery and Expansion: female tank instructors, 1979.

CHAPTER 15

RECOVERY AND EXPANSION

W

ITH MEIR AND Dayan both gone—the former into retirement, the latter having become an ordinary Knesset member and later foreign minister—Israel’s defense was entrusted to a new team. At its head was Prime Minister Rabin. The previous six years he served as Israel’s ambassador to Washington and had lost much of his wide-eyed, young-boy-from-the-provinces air. His minister of defense was Shimon Peres, an old rival, an expert on secret negotiations, and the acknowledged founder of Israel’s military, aviation, and electronics industries as well as the Dimona nuclear reactor. After Labor was thrown out of office in the 1977 elections, Rabin and Peres vented their mutual antipathy, each one going out of his way to tell the public how incompetent the other was in defense-related matters. Yet the fact remains that together they knew more about, and had done more for, Israeli security than anybody else. So long as they remained in power their rivalry did not prevent the IDF from recovering and, later, increasing its might by leaps and bounds.

ITH MEIR AND Dayan both gone—the former into retirement, the latter having become an ordinary Knesset member and later foreign minister—Israel’s defense was entrusted to a new team. At its head was Prime Minister Rabin. The previous six years he served as Israel’s ambassador to Washington and had lost much of his wide-eyed, young-boy-from-the-provinces air. His minister of defense was Shimon Peres, an old rival, an expert on secret negotiations, and the acknowledged founder of Israel’s military, aviation, and electronics industries as well as the Dimona nuclear reactor. After Labor was thrown out of office in the 1977 elections, Rabin and Peres vented their mutual antipathy, each one going out of his way to tell the public how incompetent the other was in defense-related matters. Yet the fact remains that together they knew more about, and had done more for, Israeli security than anybody else. So long as they remained in power their rivalry did not prevent the IDF from recovering and, later, increasing its might by leaps and bounds.

Elazar’s replacement as chief of staff was a paratrooper, “Motta” Gur. Self-confident to the point of rudeness, he, like Dayan, could not leave the members of the female sex alone, addressing any woman who came his way as “Hi, sweetie!” Unlike Dayan, however, who owed some of his charisma to his qualities as a litterateur, his greatest intellectual achievement consisted of a series of children’s book about Azzit, a heroic shepherd she-dog who accompanied the paratroopers on their exploits against feeble-minded Arab opponents. Having served as CO Northern Command from 1969 to 1972, he was then dispatched to Washington as military attaché, a post that usually marks the end of an officer’s career.

1

Thus he was fortunate not to have shared in the

mechdal

, which of course was the real reason behind his appointment. Also, unlike his immediate predecessors (and also unlike General Tal, who as Elazar’s chief of the General Staff was the natural candidate for the job) he was

not

an armored corps man; neither, to the present day, was any of his successors.

1

Thus he was fortunate not to have shared in the

mechdal

, which of course was the real reason behind his appointment. Also, unlike his immediate predecessors (and also unlike General Tal, who as Elazar’s chief of the General Staff was the natural candidate for the job) he was

not

an armored corps man; neither, to the present day, was any of his successors.

The “October Earthquake” notwithstanding, Israel’s top-level security decisionmaking machinery remained as rickety as ever. In 1976 the Knesset passed a new law that sought to define the relationships between prime minister, minister of defense, and chief of staff. In practice an exact division of responsibilities proved impossible to set down, and much continued to depend on the way personalities interacted. Since the Knesset still did not have subpoena power, Israel’s defense and foreign policy remained in the hands of a kitchen Cabinet—the above-mentioned trio plus Yigal Allon, who was serving Rabin as foreign minister. Depending on the occasion, these four were joined by others such as the commander of the air force, the chief of intelligence, the chief of Mossad, and other highranking security personnel. Later several prime ministers played with the idea of establishing a ministerial committee for defense, which never materialized. On other occasions the entire Cabinet was made to sit as the Ministerial Committee for Defense. But this arrangement did not work either, for twenty-odd ministers sworn to secrecy could never be trusted to keep their mouths shut.

From time to time the question of setting up a national security council was debated. The arguments in its favor were compelling: After all, the prime minister remained the sole juncture into which all channels fed, yet he did not have his own machinery to look into what he heard. From Peres to Mordechai, successive ministers of defense regarded the idea as harmful to their own authority, however, and went out of their way to torpedo it. But the ministry of defense did not succeed in constructing its own independent research and planning capability. Peres’s attempt to make the IDF planning division—it had been upgraded from branch to division—serve him as well as the chief of staff did not work well. When Sharon took over the ministry in 1981 he tried to solve the problem by setting up the National Security Unit (NSU) in the Ministry of Defense, the upshot being a sort of parallel General Staff with one major general, one brigadier general, and twenty colonels.

2

Understandably the NSU excited the animosity of Chief of Staff Eytan

3

—as indeed it was supposed to, since he and Sharon were old rivals. When Arens in turn replaced Sharon, one of his first actions was to abolish the NSU for the sake of harmony with the IDF.

2

Understandably the NSU excited the animosity of Chief of Staff Eytan

3

—as indeed it was supposed to, since he and Sharon were old rivals. When Arens in turn replaced Sharon, one of his first actions was to abolish the NSU for the sake of harmony with the IDF.

Thus, as before, neither prime minister nor minister of defense—let alone the Cabinet or the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee—succeeded in setting up a strong organization capable of doing independent research and exercising effective oversight. Also, and contrary to the recommendations of the Agranat Commission of Investigation, the IDF retained its grip over the national intelligence estimate. To be sure, there were a few cosmetic changes. During the first year or two after the war an attempt was made to get the research department of the Foreign Office to duplicate the work of the IDF’s intelligence research branch. A number of bright young men were recruited for the job, but after a while the research department languished. Though the IDF now commanded some of the world’s most advanced sensors and early-warning systems, the fear that another Arab attack would catch it by surprise continued to haunt both GHQ and individual intelligence officers. Over time, this fear led to a great outpouring of works about intelligence, its possibilities, and its limitations.

4

4

By way of correcting the inability of civilian and military decisionmakers to communicate with one another—in plain words, ensuring that the former should know exactly what a division is—the long-dead National Defense College was revived in 1976-1977. Its first commander was Maj. Gen. Menachem Meron. A Tal protégé, he had been responsible for the Sharm al-Sheikh area in 1973; by way of preparation he spent a year with the Royal College of Defense Studies in London. However, and as in its previous incarnation, the college never succeeded either in building up a first-rate faculty or in turning itself into a vehicle for selection. Intellectually its stature was reflected by the almost nonexistent library and the fact that, conspiring with Haifa University, it handed out M.A. degrees in a mere eight months (as against a minimum of two years in any other program). Functionally it acted as a pool for unemployed lieutenant colonels with the occasional civilian thrown in. The war also persuaded the IDF that its brigade commanders were unprepared for the job and led to the establishment of a special course for them. In 1994 the first higher command and general staff course (for brigadier generals) was held. However, the fact that most of them did not have good command of English precluded non-Israelis from being invited to speak; they mainly listened to their own former superiors.

With Rabin in the saddle, the country started pulling itself out of its confusion. Though there was constant trouble on the Lebanon border, the separation of forces agreements with Egypt and Syria proved their worth and enabled the IDF to rebuild. This was even more true after the “Second Separation of Forces Agreement” was concluded with Egypt in September 1975. Representing a real step toward peace, the agreement made war on the Egypt front much less likely. Should Egypt decide to go to war, however, it would have to do so in the teeth of U.S.-manned early-warning stations located in the Sinai passes. It also implied moving the forces across a twenty-mile demilitarized zone, thus simultaneously serving warning and getting out of antiaircraft missile range. Last but not least, the agreement opened the road for the IDF to receive even more U.S. weapons than before.

Yet economically speaking these were extremely difficult years. The war itself was said to have cost Israel the equivalent of a full year’s GNP. No sooner was it over than it was followed by the energy crisis, which first doubled and then quadrupled the price of oil. From 1967 on, Israel had taken about half its oil from the fields at Abu Rhodeis, but in 1975 they were returned to Egypt. Together with the need to pay for rearmament, the effect was to quadruple the gap in the balance of payments between 1972 and 1981.

5

Inflation rose to dizzying heights. At no time during the decade after 1973 did it fall below 37 percent, and in 1985 it even exceeded 400 percent.

5

Inflation rose to dizzying heights. At no time during the decade after 1973 did it fall below 37 percent, and in 1985 it even exceeded 400 percent.

Other books

Enigma:What Lies Beneath (Enigma Series Book 1) by Kellen, Ditter

Splintered by S.J.D. Peterson

LusitanianStud by Francesca St. Claire

A Stolen Tongue by Sheri Holman

Better Not Love Me by Kolbet, Dan

Daly Way 04 - One for the Team - Brynn Paulin by Menage Romance

A Taste of Sin by Jennifer L Jennings, Vicki Lorist

Deadly Fate by Heather Graham

Loving the Lawman (Roses of Ridgeway) by Alexander, Kianna

Sassy Road by Blaine, Destiny