The Sword And The Olive (18 page)

Read The Sword And The Olive Online

Authors: Martin van Creveld

In central Palestine things did not go as well. As the defenders of Jerusalem’s Jewish Quarter were approaching the end of their tether during the second half of May, the center of gravity shifted twenty or so miles west to Latrun. Here a strategically positioned police fort dominated the road toward the city; like others of its kind it had been built after the 1929 uprising and was designed to withstand, if not a regular army attack, at any rate the worst that lightly armed bands could muster. Somehow Hagana’s intelligence service missed the fact that Abdullah’s Legionaries, and not merely Palestinians, were positioned in the fortress—and that they possessed heavy machine guns and light artillery in addition to small arms. Hence preparations for the assault seem to have been somewhat haphazard.

Originally planned to start before midnight, the approach march was delayed.

20

By the time the troops, two crack battalions, reached their jumping-off positions on the morning of May 23, it was already daytime. Coming under murderous fire from machine guns and artillery positioned on the station’s roof, they did their best but were beaten back with heavy losses; abandoned in the sweltering heat, the stench of decomposing bodies spoiled the air for weeks thereafter.

21

Among the wounded was twenty-year-old Ariel Sharon, who commanded the lead platoon of one battalion (even though he had never gone through officer school). He and a few comrades barely made it back, crawling some 1,200 meters over the stone terraces while under fire all the way.

20

By the time the troops, two crack battalions, reached their jumping-off positions on the morning of May 23, it was already daytime. Coming under murderous fire from machine guns and artillery positioned on the station’s roof, they did their best but were beaten back with heavy losses; abandoned in the sweltering heat, the stench of decomposing bodies spoiled the air for weeks thereafter.

21

Among the wounded was twenty-year-old Ariel Sharon, who commanded the lead platoon of one battalion (even though he had never gone through officer school). He and a few comrades barely made it back, crawling some 1,200 meters over the stone terraces while under fire all the way.

The next attempt to recover Latrun took place on May 30. This time the infantry was supported by Napoleonchiks, armored cars, a few half-tracks, and even a couple of Cromwell tanks that had been illegally sold by British personnel. However, inexperience and faulty coordination caused this assault to be no more successful than the first.

22

Some of the infantry consisted of untrained personnel who had been mustered in the European refugee camps and were thrown into the battle a few days after their arrival with hardly any time to acclimatize themselves. Among the tank crews, one consisted of former British soldiers—mercenaries, to call things by their name—and the other of Russian immigrants who claimed to have operated tanks in the war against Germany. The two were thus unable to communicate; when the former withdrew due to mechanical failure the latter turned tail and returned to the assembly area without having fired a shot. This and similar incidents were typical of a motley, ill-organized, and illtrained—but on the whole highly motivated—force.

22

Some of the infantry consisted of untrained personnel who had been mustered in the European refugee camps and were thrown into the battle a few days after their arrival with hardly any time to acclimatize themselves. Among the tank crews, one consisted of former British soldiers—mercenaries, to call things by their name—and the other of Russian immigrants who claimed to have operated tanks in the war against Germany. The two were thus unable to communicate; when the former withdrew due to mechanical failure the latter turned tail and returned to the assembly area without having fired a shot. This and similar incidents were typical of a motley, ill-organized, and illtrained—but on the whole highly motivated—force.

Having failed to capture Latrun, the IDF, as it now was, solved the problem by improvising a road that bypassed the salient to the southwest, thereby allowing the convoys to resume their journey to Jerusalem and saving the western part of the town from sharing the fate of the Jewish Quarter. Over the next week or so—until the first truce went into effect on June 11—both sides shelled the other sporadically across the hills that separated the fortress from the road. Meanwhile the brunt of the fighting shifted even farther south. Following the lead of the Arab Legion, a battalion of Muslim Brotherhood volunteers commanded by Lt. Col. Abd al Aziz did not wait for the proclamation of the Jewish state, starting its invasion on May 10. Its attempt to capture Kfar Darom, south of Gaza, failed. However, it did occupy Iraq Suedan, another stout, British-built police station, which dominated the coastal road to the south.

Five days later the regular Egyptian army joined the invasion with two division-size task forces. One prong followed Abd al Aziz and, basing itself at Gaza, took the coastal road. It bypassed Kfar Darom, overran

kibbuts

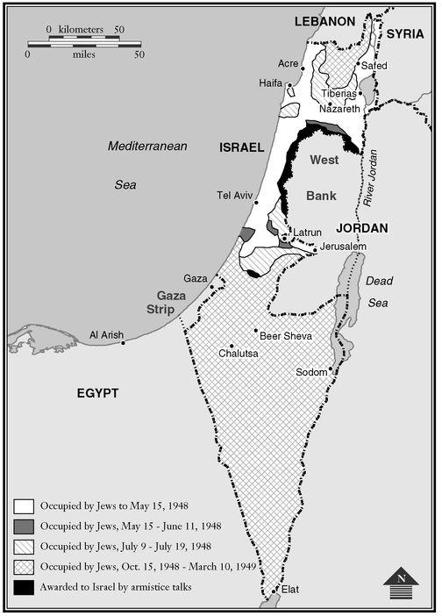

Yad Mordechai, and drove toward Tel Aviv. By May 29 it had reached as far as Ashdod, only twenty-five miles south of the main Jewish city; there, however, it was brought to a halt after a bridge had been demolished and the advance columns were attacked by four of the IDF’s newly arrived Messerschmidt fighters. The other prong entered Erets Yisrael after crossing Sinai by a different road farther south. Basing itself at Rafah, it advanced southwest and occupied Beer Sheva before driving northeast into the West Bank, reaching as far as the outskirts of Jerusalem, where it linked up with Abdullah’s troops (see Map 6.1).

kibbuts

Yad Mordechai, and drove toward Tel Aviv. By May 29 it had reached as far as Ashdod, only twenty-five miles south of the main Jewish city; there, however, it was brought to a halt after a bridge had been demolished and the advance columns were attacked by four of the IDF’s newly arrived Messerschmidt fighters. The other prong entered Erets Yisrael after crossing Sinai by a different road farther south. Basing itself at Rafah, it advanced southwest and occupied Beer Sheva before driving northeast into the West Bank, reaching as far as the outskirts of Jerusalem, where it linked up with Abdullah’s troops (see Map 6.1).

MAP 6.2 PHASES IN THE WAR OF INDEPENDENCE, 1948-1949

Like the rest of the Jewish territory, the southern front was defended partly by the settlements—all of which were more or less fortified and provided with arms—and partly by two understrength Hagana (IDF) brigades that seldom if ever operated as complete units. Early attempts to halt the Egyptians failed; settlements with defenses that proved good enough to repel Palestinian irregulars and halfhearted Syrian and Iraqi attacks were either bypassed or proved incapable of halting a full-scale assault by the Egyptian army. Attacked on all fronts simultaneously, usually the best that the former Hagana forces could do was to send platoon-size reinforcements to settlements as they came under attack. In the meantime it desperately improvised a main line of defense from Ashdod to Bet Guvrin in the east.

On June 11 a four-week truce mandated by the UN Security Council came into effect. While enabling both sides to recuperate, it worked in favor of the Jews, who had just about reached the end of their tether. Accustomed to having their armies fed by the British, Arab countries had made no special efforts to build arms acquisition organizations. Not so the

Yishuv

, which now began to reap the results of three years’ efforts buying arms and preparing them for transport to Erets Yisrael. The most spectacular acquisition was the B-17s—the famous “Flying Fortresses” used by the Allies in World War II. They arrived from Czechoslovakia on July 17, having bombed Cairo, Al Arish, and Gaza along the way;

23

other aircraft, including British Spitfire and American Mustang fighters bought in Europe, followed in the summer months.

Yishuv

, which now began to reap the results of three years’ efforts buying arms and preparing them for transport to Erets Yisrael. The most spectacular acquisition was the B-17s—the famous “Flying Fortresses” used by the Allies in World War II. They arrived from Czechoslovakia on July 17, having bombed Cairo, Al Arish, and Gaza along the way;

23

other aircraft, including British Spitfire and American Mustang fighters bought in Europe, followed in the summer months.

Meanwhile the ground forces, which carried the brunt of the war, received a small number of tanks, half-tracks, and 75mm guns. Although not all of these arms proved serviceable—for example, a handful of Sherman tanks had perforated barrels and could not be reconditioned—they enabled the IDF to establish its first “armored” brigade—with Sadeh as commanding officer. Since there were not nearly enough tanks to go around, only part of one battalion was in fact provided with them. The rest of the troops rode an ill-matched assortment of armored cars, half-tracks, and jeeps with medium machine guns affixed to their hoods. These were good enough to beat the Egyptians, as it turned out.

While Abdullah toured the Arab capitals, vainly seeking to establish a unified command with himself at its head, Ben Gurion held a series of meetings with his commanders in which the lessons of the war were discussed and strategy for the next stage laid down.

24

Perhaps most important, the four weeks of cease-fire were used to rebuild and train the formations (very necessary given that gunners, for example, received six days’ training before being sent to the front).

25

A top-level reorganization was carried out and divided the country into four fronts (north, east, center, and south). Although no permanent divisions were established, for the first time Supreme Headquarters appointed commanders at levels higher than that of brigade. When the IDF returned to action it did so not as a loose federation of twelve improvised brigades (plus equally improvised air and naval forces) but as a cohesive, disciplined force capable of coordinating operations on a countrywide scale.

26

To symbolize the change the previous improvised stripes, known as blue band ranks (after a brand of margarine), were abolished. Insignia of rank were introduced for the first time, with the names of the various grades taken from the Bible.

27

24

Perhaps most important, the four weeks of cease-fire were used to rebuild and train the formations (very necessary given that gunners, for example, received six days’ training before being sent to the front).

25

A top-level reorganization was carried out and divided the country into four fronts (north, east, center, and south). Although no permanent divisions were established, for the first time Supreme Headquarters appointed commanders at levels higher than that of brigade. When the IDF returned to action it did so not as a loose federation of twelve improvised brigades (plus equally improvised air and naval forces) but as a cohesive, disciplined force capable of coordinating operations on a countrywide scale.

26

To symbolize the change the previous improvised stripes, known as blue band ranks (after a brand of margarine), were abolished. Insignia of rank were introduced for the first time, with the names of the various grades taken from the Bible.

27

When fighting reopened on July 7, the IDF’s first objective was to eject the Syrians out of Mishmar Ha-yarden. A force of four battalions—approximately 2,000 men—concentrated in neighboring

kibbutsim.

Surprising the Syrians, it carried out the task with relative ease; however, a nighttime attempt to cross the Jordan to take the Syrian rear suffered delays and was met by a counterattack when morning broke. Several days of heavy fighting ensued, during which the IDF, feeling itself inferior in firepower, adopted its standard method: Take cover by day while engaging mobile operations by night. Despite the intervention of the B-17s, which bombed the Syrians, these battles ended in a stalemate that would last until the end of the war.

kibbutsim.

Surprising the Syrians, it carried out the task with relative ease; however, a nighttime attempt to cross the Jordan to take the Syrian rear suffered delays and was met by a counterattack when morning broke. Several days of heavy fighting ensued, during which the IDF, feeling itself inferior in firepower, adopted its standard method: Take cover by day while engaging mobile operations by night. Despite the intervention of the B-17s, which bombed the Syrians, these battles ended in a stalemate that would last until the end of the war.

Not so in lower Galilee, into which Kauji had retreated after his April defeat. Rebuilding his forces with volunteers from Lebanon, on July 12 he debouched southward intending to cut the road leading northeast from the Valley of Esdraelon, thus preparing for the eventual reoccupation of Tiberias. The ensuing battle had much in common with the earlier one at Mishmar Ha-emek; for eight days the Arab Salvation Army, supported by artillery, faced an Israeli infantry battalion engaged in a flexible defense. In the event these engagements proved to be a useful cover for “Operation Dekel (Palm Tree),” directed into Kauji’s rear from its jumping-off positions on the Mediterranean coast north of Haifa. The movement started on the night of July 15 and proceeded almost without resistance, thus proving how far the IDF had already gone in breaking the Palestinians. Nazaret surrendered on July 16, forcing Kauji to suspend his attacks and retreat north.

Meanwhile on the central front, operations during the Ten Days—that is, the period until the next truce entered into force—were equally hardfought. Two brigades widened the corridor that led to Jerusalem, one in the region south of Latrun and the other farther west in the Ramla-Lyddia area. As the Arab Legion stood by, the town of Lyddia was cleared by an “armored” battalion—in fact, half-tracks spearheaded by a former British armored car—commanded by Moshe Dayan.

28

Like an old-fashioned cavalry regiment charging a line of infantry, it drove through the main street and reversed direction, firing wildly into houses on both sides. The psychological shock caused the fall not only of Lyddia; neighboring Ramla surrendered immediately, and the IDF had captured the most important airfield in the country.

28

Like an old-fashioned cavalry regiment charging a line of infantry, it drove through the main street and reversed direction, firing wildly into houses on both sides. The psychological shock caused the fall not only of Lyddia; neighboring Ramla surrendered immediately, and the IDF had captured the most important airfield in the country.

With the areas west and south of Latrun now firmly in Israeli hands (see Map 6.2), Allon as the front commander determined that the time had come to make another attempt on the police fortress. Once again, poor intelligence concerning the strength of the Arab Legion in the area failed to register the presence of two armored cars; the Israelis had also neglected to provide the leading company with antitank weapons. In addition, and as happened during the previous attacks against the same objective, coordinating forces at night proved beyond the capability of headquarters—which for some reason was located much too far in the rear.

29

This failure was followed almost immediately by an equally abortive attempt to reconquer the Jordanian-held Old City. Mounted on July 17-18, just before the second truce went into effect, the operation was repulsed with heavy losses; its commander, David Shealtiel, was relieved.

30

29

This failure was followed almost immediately by an equally abortive attempt to reconquer the Jordanian-held Old City. Mounted on July 17-18, just before the second truce went into effect, the operation was repulsed with heavy losses; its commander, David Shealtiel, was relieved.

30

In the south, the truce had caught the Egyptian army on the eve of a major attempt to bypass Ashdod to the east by driving farther inland. Breaking the truce twenty-four hours early, the Egyptians attacked the settlement of Negba; it was their single largest operation, conducted with the aid of a reinforced brigade with three infantry battalions, an armored battalion, an armored car battalion, an artillery battalion, antitank weapons, and air support. The battle culminated on July 12 when 4,000 artillery rounds came down on the

kibbuts

—inflicting few casualties, however, since the civilian population had long been evacuated and the entire defense put underground.

31

Negba held out and the Egyptian attempt, the last one of the war, to break through the line that led from Ashdod on the Mediterranean coast to Bet Guvrin in the Judaean foothills failed. Yet the IDF’s attempt to retake Iraq-Suedan was also repulsed with losses, earning the fort its nickname—“The Monster.”

kibbuts

—inflicting few casualties, however, since the civilian population had long been evacuated and the entire defense put underground.

31

Negba held out and the Egyptian attempt, the last one of the war, to break through the line that led from Ashdod on the Mediterranean coast to Bet Guvrin in the Judaean foothills failed. Yet the IDF’s attempt to retake Iraq-Suedan was also repulsed with losses, earning the fort its nickname—“The Monster.”

The first truce had come to the IDF “like manna from heaven,” enabling it to recuperate and reorganize. Not so the second truce of July 18, which found the IDF in a much stronger position. In the north the Syrians had been definitely repulsed; only parts of eastern upper Galilee were still in the hands of Kauji, who nevertheless would be thrown out with little difficulty during “Operation Chiram” in late October. In the center, along what would become the Israel-Jordan border, large-scale fighting between the Iraqis and Jordanians had ended, except for the area around Bet Shemesh, southwest of Jerusalem, which had been reached by an Egyptian force from Hebron. In the south the last and most powerful Egyptian offensive had been broken. By contrast the Israelis, now with a rapidly growing army and in full offensive swing, were poised to take the initiative and carry it through to the end of the war.

Other books

The Fine Art of Murder by Jessica Fletcher

New Contract (Perimeter Defense Book #3) by Michael Atamanov

Yes, No, Maybe by Emma Hillman

Real Time by Jeanine Binder

The Lady and the Captain by Beverly Adam

Never Mind The Botox: Rachel by Penny Avis

Staggerford by Jon Hassler

Across the Winds of Time by McBride, Bess

BackTrek by Kelvin Kelley

Zero to Hero by Lin Oliver