The Source Field Investigations (7 page)

Read The Source Field Investigations Online

Authors: David Wilcock

The Outer Limits of Shared Consciousness

Minor anxiety disorders, like nervousness and the inability to concentrate, also were measurably improved in Dr. Braud’s studies. In an experiment from 1983, Dr. Braud and an anthropologist named Marilyn Schlitz studied a group of highly nervous people along with a group of calmer people. The nervousness of each group, in this case, could be directly measured by the amount of electrical activity on their skin. In some cases, the groups were given common relaxation techniques and instructed to calm themselves down. In other cases, Braud and Schlitz tried to calm them down by simply concentrating on them from another room. The originally calm group showed very little change by practicing the exercises or being “remote influenced,” but the nervous group became much calmer—in both cases. Surprisingly, Braud and Schlitz’s remote influencing effects upon the nervous group worked almost as well as any relaxation exercises they did for themselves.

20

Similarly, when Braud and Schlitz remotely concentrated on someone in an attempt to help him focus his attention, the subject had an immediate improvement. The people whose minds were the most apt to wander gained the strongest benefits from this process.

21

20

Similarly, when Braud and Schlitz remotely concentrated on someone in an attempt to help him focus his attention, the subject had an immediate improvement. The people whose minds were the most apt to wander gained the strongest benefits from this process.

21

Thankfully, Braud also found out that we are not helpless against these remote influences—we can shield the ones we don’t want.

22

If you visualize a protective shield, a safe, a barrier or a screen—whatever you feel comfortable with—you can indeed stop these influences from affecting you.

23

The remote influencers did not know which participants were trying to block their thoughts, but the people who did try to shield themselves were successful.

24

Other evidence suggests a positive attitude in life is your best protection, as we will see—the highest “coherence” wins.

22

If you visualize a protective shield, a safe, a barrier or a screen—whatever you feel comfortable with—you can indeed stop these influences from affecting you.

23

The remote influencers did not know which participants were trying to block their thoughts, but the people who did try to shield themselves were successful.

24

Other evidence suggests a positive attitude in life is your best protection, as we will see—the highest “coherence” wins.

Sperry Andrews put together a proposal for a series of ninety-second television spots that would demonstrate these “collective consciousness” experiments to the world—for an initial investment of $711,000 dollars.

The Human Connection Project contends that a significant number of people will share a greater sense of belonging together after watching extensive media announcements and presentations that illustrate this subject. Out of this heightened sense of connection to a larger whole, it is predicted that a new level of shared intelligence, compassion, and creativity will begin to emerge among people.

25

25

In this proposal, Andrews mentions some startling facts. More than five hundred different scientific studies have proven that human consciousness can affect biological as well as electronic systems

26

—and we will learn more about the electronic experiments later on. Schlitz and Honorton explored thirty-nine different studies during which people successfully shared thoughts and experiences—while they were physically separated from one another. The overall probability that these effects were caused by chance alone was less than one part in a trillion.

27

In some studies, ordinary people detected events that had not even happened yet in linear time.

28

-

29

In an extremely comprehensive paper on the Source Field from 2004, Robert Kenny revealed that the Institute of HeartMath developed Grinberg’s original discoveries about brain-to-brain entrainment much further:

26

—and we will learn more about the electronic experiments later on. Schlitz and Honorton explored thirty-nine different studies during which people successfully shared thoughts and experiences—while they were physically separated from one another. The overall probability that these effects were caused by chance alone was less than one part in a trillion.

27

In some studies, ordinary people detected events that had not even happened yet in linear time.

28

-

29

In an extremely comprehensive paper on the Source Field from 2004, Robert Kenny revealed that the Institute of HeartMath developed Grinberg’s original discoveries about brain-to-brain entrainment much further:

Even when participants were in separate rooms, their heart and brain waves became synchronized or entrained, when they had close living or working relationships, or when they felt appreciation, care, empathy, or love toward each other. . . . When people were able to internally entrain their own personal heart and brain waves [through meditation and other related techniques], they caused the heart and brain waves of other individuals to entrain with theirs. Entrainment appears to increase attention, to produce feelings of calm and deep connection, and to facilitate tele-prehension of each other’s sensations, emotions, images, thoughts and intuitions.

30

30

There is no turning back. These discoveries are undeniable facts. Our mind-to-mind connection, sharing our thoughts and experiences, has now been proven—at odds of more than a trillion to one against chance. Skeptics continue to boldly proclaim that “there is no evidence,” but perhaps a better phrase to use is “there is no publicity.” No one has taken Sperry Andrews’s offer to produce these groundbreaking, civilization-defining TV spots. Hardly any of this information appears in newspapers, magazines, TV shows or movies. In 2006, Britain’s premier science forum featured research from Rupert Sheldrake suggesting that some people know who is calling them before they answer the telephone—and this prompted a furious reaction among participating scientists. Dr. Peter Fenwick also presented his conclusions that consciousness survives after clinical death, and Deborah Delanoy discussed research similar to William Braud’s—showing we can influence someone else’s body by thinking about him or her. Oxford Professor of Chemistry Peter Atkins said, “Work in this field is a complete waste of time . . . there is absolutely no reason to suppose that telepathy is anything more than a charlatan’s fantasy.”

31

31

Just as this book was in its final edits in January 2011, great controversy again arose because

The Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

a highly respected science journal, decided to publish the research of Dr. Daryl J. Bem—an emeritus professor at Cornell University. What makes this research so controversial is it contains some of the most stunning proof ever revealed that human consciousness has direct access to events in the future.

The Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

a highly respected science journal, decided to publish the research of Dr. Daryl J. Bem—an emeritus professor at Cornell University. What makes this research so controversial is it contains some of the most stunning proof ever revealed that human consciousness has direct access to events in the future.

In one case, Dr. Bem wanted to see if people would “remember” words that they didn’t actually study until after they had already been tested on these words. This experiment began with the participants being given a test in which they had to memorize certain vocabulary words. After they took the test, Dr. Bem randomly chose some of the specified vocabulary words and had the participants study them closely: learn their definitions, practice with them and become comfortable with them. The words they studied in the future (after the test) became the words they memorized the most easily in the past (during the test). Another experiment proved that the emotional shock of seeing an erotic picture would actually travel backwards in time. In this case, a computer screen showed two “curtains.” The participant was told that one of the curtains would have a picture behind it, and he was asked to guess which curtain. The picture was chosen, at random, only after the participant made a guess—which the computer program had no access to. Dr. Bem found that when the computer selected an erotic picture, the participants were more likely to guess which curtain it would appear behind—an average of 53 percent of the time. Photographs that were neutral or negative did not have this effect.

32

32

Naturally, this turns everything we think we know about science and physics on its end—so many scientists are obviously “mortified” about it, and believe it is “pure craziness.”

33

Science should be about discovering the truth, and that requires an open mind. Dr. Bem’s research is very sound—it just reveals new things about ourselves, and about reality, that most people do not already know. The data is there—but up until very recently, the publicity has been lacking. Hopefully the publication of Dr. Bem’s paper will help start a new trend.

33

Science should be about discovering the truth, and that requires an open mind. Dr. Bem’s research is very sound—it just reveals new things about ourselves, and about reality, that most people do not already know. The data is there—but up until very recently, the publicity has been lacking. Hopefully the publication of Dr. Bem’s paper will help start a new trend.

Obviously, some of the problem is that we are constantly being bombarded with new information, and it is increasingly difficult to sort through all of it. However, this research is obviously far more important than the latest news about which celebrity got drunk, angry, naked or arrested, or photographed in some embarrassing way. It does appear, however, that these same celebrities can get addicted to being stared at—as we now know there is a very real energy high they get from all the attention.

The Backster Effect occurs within each and every cell, as we saw in his studies with the white blood cells from a human mouth. However, many ancient traditions adamantly insisted there is a master gland in the human body that is responsible for pulling in thoughts and images from the Source Field, and sending our own thoughts back out. In the next chapter, we will pursue this intriguing investigation—and see if modern science can shed any new light on this ancient mystery.

CHAPTER THREE

The Pineal Gland and the Third Eye

M

any different ancient traditions say there is a physical gland, nestled deep within the center of the brain, where telepathic thought transmissions and visual images are received. This tiny pinecone-shaped gland is known as the epiphysis or pineal gland, and is about the size of a pea. In fact, the word “pineal” comes from the Latin

pinea,

which means “pinecone.” Ancient cultures all over the world were fascinated by the pinecone and pineal-gland-shaped images, and consistently used them in their highest forms of spiritual artwork. Pythagoras, Plato, Iamblichus, Descartes and others wrote of this gland with great reverence. It has been called the seat of the soul. Obviously, if this “third eye” is receiving direct impressions from the Source Field, we have not yet identified how such a mechanism might work—but that doesn’t necessarily mean the ancients were wrong.

any different ancient traditions say there is a physical gland, nestled deep within the center of the brain, where telepathic thought transmissions and visual images are received. This tiny pinecone-shaped gland is known as the epiphysis or pineal gland, and is about the size of a pea. In fact, the word “pineal” comes from the Latin

pinea,

which means “pinecone.” Ancient cultures all over the world were fascinated by the pinecone and pineal-gland-shaped images, and consistently used them in their highest forms of spiritual artwork. Pythagoras, Plato, Iamblichus, Descartes and others wrote of this gland with great reverence. It has been called the seat of the soul. Obviously, if this “third eye” is receiving direct impressions from the Source Field, we have not yet identified how such a mechanism might work—but that doesn’t necessarily mean the ancients were wrong.

The pineal gland is not technically a part of the brain; it is not protected by the blood-brain barrier.

1

It exists in the approximate geometric center of the brain’s mass, has a hollow interior filled with a watery fluid, and receives more blood flow than any other part of the body except the kidneys. Since it is not protected by the blood-brain barrier, the fluid inside the pineal gland gathers an increasing amount of mineral deposits, or “brain sand,” over time—which have optical and chemical properties similar to the enamel on your teeth.

2

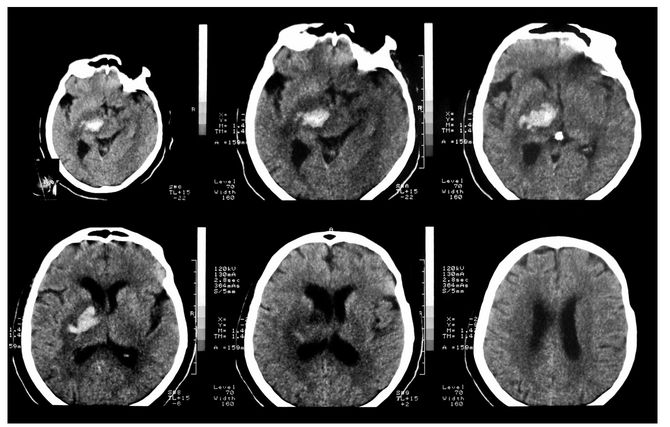

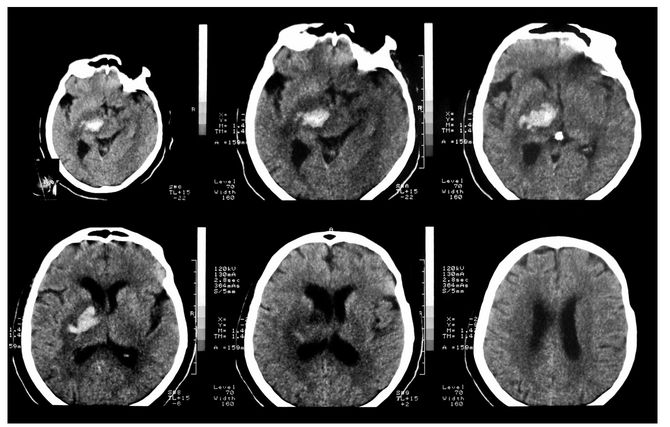

This calcification appears as a bonelike mass in the center of your brain on an X-ray or MRI. Doctors use this hard, white cluster to tell if you have a brain tumor. If the white dot appears to be pushed off to one side in your scan, they know a tumor has changed the shape of your brain.

1

It exists in the approximate geometric center of the brain’s mass, has a hollow interior filled with a watery fluid, and receives more blood flow than any other part of the body except the kidneys. Since it is not protected by the blood-brain barrier, the fluid inside the pineal gland gathers an increasing amount of mineral deposits, or “brain sand,” over time—which have optical and chemical properties similar to the enamel on your teeth.

2

This calcification appears as a bonelike mass in the center of your brain on an X-ray or MRI. Doctors use this hard, white cluster to tell if you have a brain tumor. If the white dot appears to be pushed off to one side in your scan, they know a tumor has changed the shape of your brain.

The pineal gland, a pea-sized endocrine gland located in the geometric center of the brain that fascinated many ancient cultures. Notice the pinecone shape.

X-ray images showing tumor in left ventricle of the brain. Calcified pineal gland appears in the top-right image as a round white mass, slightly offset by the tumor.

As I detailed in my online documentary

The 2012 Enigma,

3

pinecones are prominently featured in sacred art and architecture from all over the world—in an apparent homage to the pineal gland. This is a truly astonishing phenomenon that has never been adequately explained. A Christian article entitled “Pagans Love Pine Cones and Use Them in Their Art” has many pictures that prove the point

4

:

The 2012 Enigma,

3

pinecones are prominently featured in sacred art and architecture from all over the world—in an apparent homage to the pineal gland. This is a truly astonishing phenomenon that has never been adequately explained. A Christian article entitled “Pagans Love Pine Cones and Use Them in Their Art” has many pictures that prove the point

4

:

• A bronze sculpture of a hand from the mystery cult of Dionysus in the late Roman Empire has a pinecone on the thumb, amidst other strange symbols;

• A Mexican god holds pinecones and a fir tree in a sculpture;

• A staff of the Egyptian sun god Osiris from a museum in Turino, Italy, has two “kundalini serpents” that entwine together and face a pinecone on the top;

• The Assyrian/Babylonian winged god Tammuz is pictured holding a pinecone;

• The Greek god Dionysus carries a staff with a pinecone on top, symbolizing fertility;

• Bacchus, the Roman god of drunkenness and revelry, also carries a pinecone staff;

• The Catholic pope carries a staff with a pinecone directly above where his hand is positioned—and the staff then extends up into a stylized tree trunk;

• Many Roman Catholic candle holders, ornaments, sacred decorations and architectural samples feature the pinecone as a key design element;

• The largest pinecone sculpture in the world is prominently featured in Vatican Square—in the Court of the Pinecone.

Other books

Phase Space by Stephen Baxter

A Soldier's Story by Blair, Iona

Crooked River: A Novel by Valerie Geary

Beasthood (The Hidden Blood Series) by A.Z. Green

The Ex (The Corny Myers Series) by Kleve, Sharon

DeliveredIntoHisHands by Charlotte Boyett-Compo

Wilson Mooney, Almost Eighteen by Gretchen de la O

The Norse Directive by Ernest Dempsey

Beautiful Sins: Leigha Lowery by Jennifer Hampton