The Sexual History of London (30 page)

Read The Sexual History of London Online

Authors: Catharine Arnold

One of the chief opponents of the Act was Lord Lyndhurst, who initiated the long-running debate as to the meaning of the term âobscenity': âbut what is the interpretation which is to be put upon the word “obscene”?' he asked. âI can easily conceive that two men will come to entirely different conclusions as to its meaning.' Lyndhurst spelt out his objections by describing one famous painting thus: âa woman stark naked, lying down, and a satyr standing by her with an expression on his face which shows most distinctly what his feelings are, and what is his object'. This sounded like just the sort of smut available in Holywell Street, until Lyndhurst revealed that he was actually describing Correggio's

Jupiter and Antiope

(1523), but his description also shows that one man's Renaissance masterpiece is another man's obscenity. And obscenity was to remain almost impossible to define far into the twentieth century, as attested by a number of controversial court cases.

Lord Campbell's definition of obscenity was âintended to apply exclusively to works written for the single purpose of corrupting the morals of youth, and of a nature calculated to shock the common feelings of decency in any well-regulated mind'. His law was designed to eliminate the âsale of poison more deadly than prussic acid, strychnine or arsenic', and would âprotect women, children, and the feeble-minded'.

27

The Act gave the police the power to search premises, but not people, where such publications were on sale, and permitted customs officers and Post Office officials to destroy consignments, and to prosecute offenders.

For all Lord Lyndhurst's efforts, the authorities refused to draw a distinction between high art and smut. In 1872 the publisher Henry Vizetelly was fined £100 and bound over for twelve months for publishing the English translation of Zola's

La Terre

. âNothing more diabolical has ever been written by the pen of man,' declared one Member of Parliament,

28

but this did not prevent Vizetelly bringing out the book again and being sent to prison for three months. In 1875 the Society for the Suppression of Vice campaigned against âthe book entitled Rabelais', a translation of the French genius. This objection provoked an inspired rant in the pages of

The Athenaeum

from Swinburne. Given that even established French scholars could scarcely understand what âthe book entitled Rabelais' was about, asked Swinburne, what right had the Society to object to it? What, pray, he demanded, was the Society going to do about âthe book entitled the Bible' or âthe book entitled Shakespeare?'

29

Were they intending to suppress these pillars of English culture as well? When the Society responded that they had no plans to ban the Bible or Shakespeare, Swinburne responded ironically. What! Were they really going to continue to let Shakespeare be sold in public? In W H Smith's stalls, on railway stations! What a shocking dereliction of duty.

30

The Society for the Suppression of Vice did little to suppress the ingenuity and resourcefulness of Victorian pornographers. One method of avoiding prosecution under the Obscene Publications Act was to circulate books privately amongst the members of a society. This was the route taken by Sir Richard Burton, who created the Kama Shastra Society with Forster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot to print and circulate books which it would be illegal to publish in public. Burton's translation of

The Arabian Nights

was printed by the Kama Shastra Society and circulated in a subscribers-only edition of 1000 with a guarantee that there would never be a larger printing of the book in this form.

Burton had developed a fascination with the sex lives of the different cultures he encountered during his career as an army officer and spy. Fascinated by Islam, he became the first Western man to enter Mecca, disguised as an Arab. One of the first real sexologists, Burton even recorded the measurements of the penises of various inhabitants in his travel books. He also described sexual techniques common in the regions he visited, often hinting that he had participated, breaking both sexual and racial taboos. If not genuinely homosexual, Burton may have engaged in homosexual acts in the spirit of observer participation. He never directly acknowledges homosexuality in his writing but the rumours began in his army days, when he was allegedly asked by General Sir Charles James Napier to go undercover and investigate a male brothel reputedly frequented by British soldiers. His report was said to be so detailed that some believed he had been a punter, but as no report survives this may have been one of the many examples of the self-aggrandizing myth-making which Burton so enjoyed. According to the damning obituary by the French novelist Ouida in the

Fortnightly Review

in June 1906, âhe was ill fitted to run in official harness, and he had a Byronic love of shocking people, of telling tales against himself that had no foundation in fact'.

Burton's 1885 unexpurgated version of

The Arabian Nights

should not be confused with Andrew Lang's edition of 1898, designed for children.

The Arabian Nights

was one of the first English-language texts to address the practice of pederasty, which Burton claimed was prevalent in an area of the southern latitudes that he referred to as the âSotadic zone', a reference to Sotades, the Greek homoerotic poet. This increased the speculation and rumours about Burton's own sexuality that were already circulating. Typically, Burton took the credit for a translation of the

Kama Sutra

which appeared in 1883, although the majority of the work had been undertaken by Indian scholars.

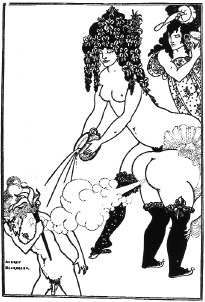

While many of the illustrations in the Holywell Street genre were indeed as crude in execution as they were in subject matter, the field did produce one

bona fide

artistic genius in the form of Aubrey Beardsley (1872â98). Beardsley was a gifted and distinctive illustrator who became art editor of

The Yellow Book

, a literary magazine which showcased famous writers and artists such as Sir Frederick Leighton, John Singer Sargent, Max Beerbohm and Henry James. Although notionally âdecadent', the âyellow' wrapper having been borrowed from the yellow dust-jackets which Parisian publishers used to signify the âadult' content of their novels,

The Yellow Book

was a highly respected publication. When Beardsley was sacked for obscenity, he collaborated with Leonard Smithers on the short-lived but influential magazine

The Savoy

, where his talents flourished. This led to a new development in British publishing, that of beautifully produced âerotica' such as Beardsley's illustrations for Pope's âRape of the Lock', his own romance entitled

Under the Hill

and an illustrated retelling of

Lysistrata

, Aristophanes' anti-war sex-strike comedy. These illustrations are fantastically delicate but sexually explicit renditions of naked young women reaching out to one another's pudenda, naked dwarves with giant penises reminiscent of Priapic Roman statuary, and mysterious pagan rituals featuring satyrs and the great god Pan. A vein of wit runs through these exquisite visions, as in the depiction of the grumpy middle-aged woman stumping upstairs after a night out who, it transpires, is

Messalina, Returning from the Bath

, off to pester her husband after being left unsatisfied by a night in the stews.

As a delicate, sensitive and artistic young man, Beardsley was inevitably interrogated about his sexual orientation. When the critic Haldane MacFall questioned his virility, classing him with Oscar Wilde as âeffeminate, sexless, and unclean', Beardsley responded tartly: âAs for my uncleanliness, I do my best for it in my morning bath, and if your critic has really any doubts as to my sex, he may come and see me take it.'

31

Despite this unfortunate start to their relationship, MacFall later became one of Beardsley's most devoted supporters.

32

Beardsley was a consumptive; when the poet John Addington Symonds visited, he found the young artist âlying out on a couch, horribly white' and wondered if he had arrived too late,

33

while the poet W. B. Yeats encountered him at a party thrown by Smithers, âpropped up on a chair in the middle of the room, grey and exhausted, and as I came in he left the chair and went into another room to spit blood'.

34

While Beardsley's friends and detractors wondered if he had even experienced any of the perverse erotic scenes which figured in his drawings, and speculated that his imagination exceeded his performance, Sir John Rothenstein denied that his âmorbid tendencies' were âexpressed in his art alone. I have the best authority for believing this to be wholly untrue, for asserting that during one short period of his life he was very dissolute.'

35

As well as the allegations that he was homosexual, rumours also circulated to the effect that he had an incestuous relationship with his sister, Mabel, which resulted in a miscarriage, one explanation for the disturbing images of foetus-like monsters which recur in his art.

An illustration by Aubrey Beardsley for Aristophanes' anti-war comedy

Lysistrata,

1896.

Sadly, Beardsley did not live to fulfil his promise, but succumbed to tuberculosis in 1898, pleading with Smithers to destroy all his illustrations to

Lysistrata

âby all that's holy',

36

after experiencing a deathbed conversion to Roman Catholicism. He was twenty-six years old. Fortunately for us, Smithers does not appear to have complied, and the illustrations remained in circulation.

Leonard Smithers (1861â1909), described by Oscar Wilde as âthe most learned erotomaniac in Europe', was a new breed of pornographer, a very different creature from the pathetic creep Hankey and the corrupt Dugdale. With his âsingularly clear cut aristocratic features', Smithers cut a dash in the shady world of dirty books; his authors included Oscar Wilde, Sir Richard Burton and Aleister Crowley, and Smithers did well out of them, acquiring a house in Bedford Square and a flat in Paris. He posted a slogan outside his Bond Street bookshop reading âSmut is Cheap Today' and the money poured in. However, Smithers was not without his troubles. His wife became an alcoholic, and he himself dabbled in drink and drugs. In addition to this, he developed a taste for young girls. According to Oscar Wilde, âhe loves first editions, especially of women: little girls are his passion'.

37

He fell out with a colleague after being photographed having sex with his colleague's wife in the basement of their house, and went bankrupt in 1900. In 1909, he was found dead in his shabby lodgings in Cubitt Street, Islington, which contained nothing but the bed he died on, two empty hampers, and fifty empty bottles of Chlorodyne, a patent medicine containing laudanum, chloroform and cannabis.

Not every pornographer met such an ignoble fate. When Henry Spencer Ashbee died in 1900, it was revealed that he had bequeathed his entire collection of 15,299 pornographic books to the British Museum. At first, this august institution demonstrated reluctance in the face of such largesse, but when it was made plain that the museum would also receive Ashbee's outstanding collection of all the editions and translations of Cervantes'

Don Quixote

the bequest was finally accepted.

38

There was to be no bonfire at the bottom of the garden for Ashbee's collection. Wisely, he had blackmailed the British Museum into taking it, rather than have it destroyed or broken up into lots and auctioned off by dealers.

Henry Spencer Ashbee was the Victorian pornography collector

par excellence

, as the scale of his collection indicates. As a London merchant whose business often took him to mainland Europe, he amassed a handsome fortune which enabled him to devote his spare time to travel and collecting books, some legitimate, some less so.

39

In addition to accumulating the finest collection of Cervantes outside Spain and a selection of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English watercolours, Ashbee had the most elaborate and extensive collection of pornography ever to have been assembled by a private individual. He also inherited a sizeable collection of sado-masochistic material from Frederick Hankey, after the latter's death in Paris in 1882. But Ashbee was not simply a collector. He was also an author, publishing the

Index Librorum Prohibitorum

:

Being Notes Bio-Biblio-Icono-graphical and Critical

,

on Curious and Uncommon Books

under the pseudonym âPisanus Fraxi'. Even taking into account the scatological

nom de plume

(âPisanus' means âPiss anus' while âFraxi' is simply from the Latin â

fraxinus

' or ash tree) this tome does not at first sound promising, but when it appeared in March 1877 it transpired that this labour of love was an exhaustive survey of erotic literature, catalogued by the mysterious benefactor of Victorian pornography.