The Sexual History of London (40 page)

Read The Sexual History of London Online

Authors: Catharine Arnold

The Revue Bar closed in 2004, a victim of the new permissiveness; soft-porn âlads' mags', the internet, cable television and DVDs rendered such venues superfluous; lap-dancing clubs offered more salacious entertainment; and Soho itself had been cleaned up by Westminster City Council on the orders of Dame Shirley Porter in the 1980s. Proprietors were forced to adopt discreet shop fronts and all blatant displays of nudity or sexual activity were banned. Just as New York's raunchy Times Square was sanitized under Mayor Giuliani, London's Soho lost its raffish quality beneath a tide of creeping gentrification, coffee shops and wine bars. Media types replaced alcoholic painters and dissolute journalists in the old pubs, and the

milieu

became just another part of the London heritage experience.

London's prostitutes responded by starting to fight back. Supported by the English Collective of Prostitutes (a lobbying organization founded in 1975), one group of whores from Shepherd Market put up a spirited resistance to Westminster City Council's clean-up campaign in May 2009. Shepherd Market is a small quarter of Mayfair between Curzon Street and Piccadilly. Mayfair has always been one of the smartest addresses in London, realm of the super-rich and, traditionally, of the prostitute. From the eighteenth century onwards, Shepherd Market had been associated with high-class prostitutes. For years, the working girls and the aristocrats lived side by side; in the mid-1970s, up to one hundred girls walked the streets of the district every night, waiting for their regulars. Commissionaires in the grand hotels of Park Lane would tell families of tourists not to go to Shepherd Market because of the gauntlet of girls they would have to run. On one occasion, a gang of girls set upon and beat up an American tourist. They were convinced she was a new prostitute trying to move in on their territory. In fact, the unfortunate woman was just a little provocatively dressed.

Focus Cinema, Brewer Street, W1, in 1976, before Westminster City Council imposed advertising restrictions on the sex trade.

As organized crime strengthened its grip on London, many of the Shepherd Market girls became targets for pimps and petty criminals. With corruption rife in the Metropolitan Police, particularly the vice squad, local residents felt helpless in the wake of a crime wave. âA girl was financing three people from the game as well as herself: her landlord, her ponce and the local police,' remembers one local resident, when interviewed by the

Independent.

Things became so bad that in 1978 we established the Save Shepherd Market Campaign and took a murder map along to the House of Commons. This showed the position of every murder, act of arson and defenestration of prostitutes that had taken place in the previous 12 months. It was a horrific document. Three days after that, I had my restaurant raided and turned over by the police. It was a public statement, not so much to me as to those who lined their pockets.

15

Eventually, enforcement action from Westminster City Council and an anti-corruption drive by the Metropolitan Police resolved the issue. These days, you are more likely to walk past expensive bars and restaurants than brothels, and the shabby old pub the Maisonette has been replaced by a mosque serving the quarter's wealthy Arab residents. However, not all the prostitutes have fled. In 2009, when police raided flats in Shepherd Market and reported the prostitutes to the council's planning department, council officials wrote to them accusing them of âa change of use from residential accommodation' â in other words, running a business from a private address, which constitutes a breach of planning law. According to Niki Adams of the English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP), âthe women have been working here safely for more than a decade, which means they haven't “changed use” of the properties. The women are a welcome part of the community here and should be allowed to run their businesses without hassle from the police or council.'

16

Niki Adams's statement represented a fight-back by prostitutes against the council. In February 2009, when the Metropolitan Police closed a brothel in Dean Street, Soho, the decision was overturned by the magistrates following lobbying from the ECP. This body also campaigned against the closure of the estimated sixty to a hundred flats used by prostitutes across the borough, supported by residents who maintained that the working girls were an integral feature of the diverse local community.

Back in Shepherd Market, the ECP's argument was that evicting prostitutes from their flats would mean that they were forced to work the streets, where they faced increased danger. âMegan', a London prostitute for twenty-five years, has worked out of a Shepherd Market flat for fifteen years and was reluctant to go anywhere else.

âIt's a little village here and we couldn't work in a better place,' she told the

London Informer

newspaper. âOver the years we have had a great relationship with the police. Whenever they need help tracing a girl who has gone missing they come up and ask our help, because we are open and know everybody. The eight girls here in the flats have all been working for a long time. I don't know why suddenly we have become the enemy. The community supports us and perhaps the council did not realise that when they started sending threatening letters out.'

17

Megan appreciated that there were problems with the sex industry, and young girls being coerced into working as prostitutes, but pointed out that by being driven onto the street, she and her colleagues would be put at risk. âIt's a hard time for us, the recession is hitting our clients and the new laws are making them scared to come to us â even if they've been with us for years.'

18

The new laws Megan referred to represented yet another attempt to clean up prostitution, but for the working girls they may prove as punitive as previous legislation. The Policing and Crime Bill, passing through Parliament at the time of writing, aims to curb sex trafficking and protect women from being coerced into the sex trade. However, according to opponents, it would potentially criminalize men paying for consensual sex with a prostitute and women who employed maids or other workers to help them, damaging their business and forcing them to take greater risks. While in theory the bill appears to defend prostitutes, in practice it may become oppressive. According to Megan: âIf the police carry on raiding us, we will lose customers and then be forced onto the streets. We will then be in the same danger as the women the police say they want to protect. It doesn't make sense. But we will stand firm and fight any attempts to close us down.' And so they did. In May 2009, the working girls successfully overturned Westminster City Council's attempts to oust them from their flats in Shepherd Market. Megan's parting shot to her interviewer on the

London Informer

proved prophetic: âThis is the oldest business in the world and we're not going anywhere.'

19

Indeed, it was business as usual, âthe oldest business in the world', in one of the oldest cities in the world.

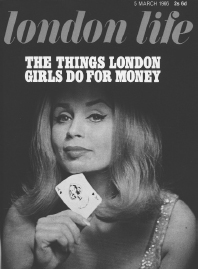

A âWest End Girl' illustrates an investigation into the sex trade, 1966.

Sex in the twenty-first century

As I wandered around the West End retracing the footsteps of the Victorian âCyprians' in Burlington Arcade, Megan's rallying cry rang in my ears. She was not going anywhere. Or at least she was not intending to go far from her present flat in Mayfair. And neither were thousands like her. There would always be prostitution in London, just as there would be many other expressions of sexuality, and it seems reasonable that the girls get the protection and support they need from the authorities, rather than having to rely on pimps; they obviously provide a much needed service and deserve better conditions than those poor wretches we met at the beginning of the book, shivering on the Bankside in their chains.

One thing that our sexual odyssey of London over the past two millennia has proved to me is that

plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose

â the more things change, the more they remain the same. As we emerge, blinking, into the sunlit uplands of the twenty-first century it is tempting to believe that we have progressed. Away with sexual guilt, priggish repression and Victorian Puritanism! With the advent of Sigmund Freud, Marie Stopes and the torrent of sex manuals which their disciples unleashed upon the world, from

Married Love

to the unintentionally hilarious

Joy of Sex

, and the sexual licence unleashed by two world wars, it might be reasonable to think that our secret sins and peculiar vices have disappeared in favour of briskly clinical couplings. Mercifully, nothing could be further from the case. London continues to yield its own rich crop of secret affairs, obscenity trials and sex scandals, every bit as byzantine as those of the preceding years. There will always be a boy in Piccadilly, leg hooked up on the wall behind him, indicating availability; there will always be a comely matron, prowling the Arcade, with a welcoming smile for the right man; or a slender brunette eyeing up a silver-haired old charmer. The bawds, the rogues, the villains and the beauties weave their eternal dance through London as they always did. These days, the Mother Needhams greet the trains at St Pancras; calculating pimps size up the trusting Scottish boys who arrive at Euston and are drawn, mothlike, to the bright lights of Piccadilly Circus; and resilient young women decide that lap-dancing or two years in a brothel represent a better way to fund their PhDs than yet another bank loan.

Such is the case of âBelle de Jour', whose lucrative but short career in the oldest profession was made possible by that most recent phenomenon, the internet. With the advent of cyberspace, pornography took on a radical, electronic form, and proved impossible to control, eroding conventional methods of censorship. Prostitutes and writers of erotica were quick to seize on its potential and none more so than âBelle de Jour', who first came to public attention in 2003 when she began to post her âDiary of a London Call Girl'. With a pseudonym derived from Luis Buñuel's 1967 film starring Catherine Deneuve as a bourgeois housewife who works in a brothel to relieve her

ennui

, âBelle' soon built up an enormous fanbase.

Subsequently issued in book form and inspiring a television series,

Diary of a London Call Girl

represented a development in the history of sex, a collision between the world's oldest profession and the latest technology. But the result was familiar enough, an attractive young woman confiding her exploits just as Fanny Hill had breathlessly narrated her adventures two centuries earlier. âBelle' inspired a slew of imitators, a new genre of popular erotica untroubled by the harsh censorship which had plagued writers such as D. H. Lawrence; it is a sign of the times that one can purchase books with titles such as

Confessions of a New York Call Girl

at the supermarket alongside the weekly grocery shop. Many attempts were made to unmask âBelle', and she had been variously suspected of being the author Toby Young, Rowan Pelling, former editor of the

Erotic Review

and chick-lit writer Isabel Wolff. Finally, in November 2009, threatened with exposure by the

Daily Mail

, the real âBelle de Jour' stepped forward in the glamorous form of research scientist Brooke Magnanti. Just as Cleland had written

Fanny Hill

to get out of debt, so Magnanti had worked as a high-class prostitute to subsidize her PhD in forensic pathology. Given the choice of £200 an hour on the game or a fraction of that wage working in a bookshop, Magnanti had chosen the more lucrative option; she also maintained that she had paid her taxes, so was not guilty of tax evasion. Magnanti's employers took an enlightened attitude: while such a revelation might once have been a sacking offence, the University of Bristol stood by her, arguing that her past was not an issue.

Magnanti's experience of the sex trade seems to have been a positive one; she has benefited and has moved on, just like Sarah Tanner, the Victorian prostitute interviewed by Arthur Munby in the 1850s who went into streetwalking as a professional venture, quit while she was ahead and opened a coffee shop out of the proceeds. Magnanti's experiences seem to bear out the words of a young woman interviewed by Mayhew, who told him pertly that she wasn't at all worried about what would become of her, and could marry tomorrow if she liked. Perhaps Dr Acton, the Victorian reformer, had been correct when he wrote that âonce a harlot always a harlot' was a myth.

But many commentators believe that there are also victims among the hard-working working girls, the twenty-first-century equivalents of the Roman sex slaves. Just a month before the unmasking of âBelle de Jour' dominated the headlines, a moral panic broke out over sex trafficking. When government minister Denis MacShane appeared on

Newsnight

arguing that the new Policing and Crime Bill was necessary to prevent trafficking, fellow guest Niki Adams, of the English Collective of Prostitutes, challenged MacShane to produce one shred of evidence that women from Eastern Europe, Africa and the Far East were being brought into the United Kingdom to work as prostitutes. Adams's scepticism at MacShane's claims prompted an investigation by the

Guardian

newspaper which concluded that not one single trafficker had been arrested during a six-month investigation into the sex trade and that trafficking had been overstated as one of the reasons women entered prostitution. Campaigners such as Niki Adams responded that the investigations into sex trafficking served no purpose and merely added to the demonization of young women, many of whom were mothers, and who had gone into prostitution because they had no other means of earning a living.

1

For these women, prostitution was business as usual, âthe oldest business in the world', in the words of Megan from Shepherd Market.

And then there are the rest of us, the amateurs, seeking affirmation in the form of fast love, cruising, cottaging, passionate sex with a complete stranger, longing for the love of women, the love of men, searching for similarity and comfort and the satisfaction of physical and emotional needs. Sexual desire is the most basic of human impulses, the desire for the âlittle death' (â

la petite mort

', or orgasm) which will distract us from the inevitable event, the hour of death that lies in store for every one of us. In the words of Andrew Marvell in his âOde to His Coy Mistress', it is our way of defying the tomb:

Had we but world enough, and time,

This coyness, lady, were no crimeâ¦

But at my back I always hear

Time's wingèd chariot hurrying near;

And yonder all before us lie

Deserts of vast eternity.

Thy beauty shall no more be found,

Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound

My echoing song; then worms shall try

That long preserv'd virginity,

And your quaint honour turn to dust,

And into ashes all my lust.

The grave's a fine and private place,

But none I think do there embrace.

Now therefore, while the youthful hue

Sits on thy skin like morning dew,

And while thy willing soul transpires

At every pore with instant fires,

Now let us sport us while we may;

And now, like am'rous birds of prey,

Rather at once our time devour,

Than languish in his slow-chapp'd power.

Let us roll all our strength, and all

Our sweetness, up into one ball;

And tear our pleasures with rough strife

Thorough the iron gates of life.