The Search for the Red Dragon (21 page)

Read The Search for the Red Dragon Online

Authors: James A. Owen

“Because,” Jack chimed in, “he’s a Longbeard.”

“So are we,” Charles said, gesturing at the others. “Do you trust

us

?”

“That’s different,” said Jack. “You’re only adults on the outside—but on the inside, you’re just like me.”

“Okay!” Laura Glue exclaimed as she and Daedalus returned to the workshop, laden with bundles. “We’re ready to go save the world!”

It was decided that they wouldn’t wake the other children, but would let them slumber as the companions left. John made the suggestion in part to hasten their departure, but also because he realized that leaving would be more difficult for Aven if she had to say good-bye to all her friends.

There had been some discussion as to whether Jack and Laura Glue should remain behind, in the safer confines of Haven, but Laura Glue insisted that she could be an invaluable guide, since she had been born in the Underneath. And Jack refused to stay on more practical grounds: The missing Lost Boys had been taken from Haven to begin with, and even Peter Pan couldn’t protect them. The safest place for him to be was with the others whom Peter was depending on to save them all.

Daedalus hugged Aven and Laura Glue and walked with the group of travelers to the westernmost gate of Haven. He opened the gate but did not step through.

“Go ahead,” John said to the others. “I want to speak with Daedalus a moment.”

When the rest of the companions were safely out of earshot, Daedalus folded his hands behind his back and looked question

ingly at John. “Yes, Caveo Principia?”

“You

can’t

leave, can you?” John said in a low voice.

Daedalus looked at him as if to say something defiant, then deflated slightly and shook his head, looking down at the edges of the stonework that marked the limits of Haven’s foundation.

“You didn’t take your father’s name, did you?” John continued. “You

are

Daedalus.”

The inventor didn’t answer right away, but instead looked out across Haven and sighed deeply.

“After Icarus’s death, Iapyx wouldn’t speak to me,” he said at last. “He believed it was my arrogance that had caused the death of his brother, and I cannot disagree. But I could not see it until it was too late.

“Daedalus, the self-obsessed instrument of his own son’s death, could never atone for that sin. But another son of Daedalus, who takes the name of his father and continues his work out of respect for the values he once had, might restore honor to the family, if not to its patriarch. Do you understand?”

“I think so,” John said after a long pause, “but I’m not sure what purpose is served by keeping your identity secret from Aven or the Caretakers.”

Daedalus sighed again. “It’s not so much that it’s a secret,” he explained, watching the others in the near distance. “Every child who comes to Haven takes a new name. To them it’s a new beginning, an opportunity to start over, without being judged for who they may have been before. I simply wanted to afford myself the same chance.”

“By masquerading as yourself?” asked John.

“By portraying myself as someone who chose to honor, rather

than blame,” Daedalus replied. “But even after all these years, after all the good I have done, my name is still remembered because I murdered my nephew and caused the death of my son.”

John shook his head. “It isn’t what I would have chosen,” he said. “The fact that you pretend to be your younger son means that all of the good you have done isn’t credited to you, it’s credited to him. What good is atonement if it isn’t yourself doing the atoning?”

Daedalus didn’t answer but stared hard at John, then turned to walk back into Haven.

“Be well, Caveo Principia,” he called out without looking back.

John watched as Daedalus disappeared into the spires of Haven, then turned and ran to catch up with his friends.

The light of the Underneath was beginning to change the sky from deep umber darkness to the colors of bruised fruit. In front, Laura Glue led the companions with a bronze lamp that cast a bright glow all about them. Jack, to his friends’ slight dismay, skirted the edges of the light, jumping in and out of its gleam, delighting in the interplay of his two shadows. The companions moved in a straight line, due west, and as they walked, they discussed the events of the night.

“When Daedalus mentioned the King of Crickets,” Charles said to Bert, “I thought you were going to be felled in a faint. What was it about the name that bothered you so?”

Bert suppressed a shudder. “It’s another old story, one that proved too dark even for the Brothers Grimm,” he said, “although it was Jacob who originally retold the tale in one of the Histories.

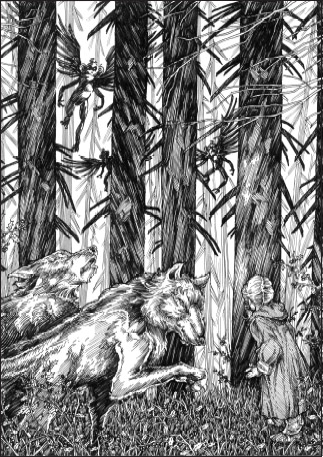

The other wolves had already begun to growl…

“The King of Crickets is the quintessential boogeyman,” Bert explained. “The movement in the dark. The creature under the bed. The monster in the closet. He is Nightmare personified, and he is very, very real.

“There are many such monsters in the world. They have always existed, and probably always will. But what frightened me was the idea that the King of Crickets was also a Pan. That would explain how his legend grew among the children, more so than grown-ups.”

“Do you think the King of Crickets and Orpheus are one and the same,” asked John, “since the myth originated with him?”

“I hope not, lad,” Bert said, shuddering again. “From what Daedalus said, Orpheus’s only motivation in taking the children was to bring them here, to be playmates to Hugh and William. But according to Jacob Grimm’s History, the children taken by the King of Crickets were never heard from again.”

“Why is it that all fables and fairy tales involve children in peril?” wondered Charles. “Was there some great assembly of storytellers that decided the best tales to tell children should also frighten them to death?”

“It’s the Longbeards who do it,” said Jack, playing hopscotch with his own shadows. “They tell us those stories to frighten us into behaving, so that we’ll value their protection. But we don’t listen, because we know the one thing that grown-ups forget….

“All stories are

true

. But some of them never

happened

.”

HAPTER

N

INETEEN

The Gilded Army

Unlike the crossing

between Croatoan Island and Haven, which could be forded at low tide, the gulf between Haven and Centrum Terrae could only be traversed by bridge.

The west side of Haven ended in a high bluff, to which the bridge was anchored. It was constructed of thick cables and ancient wood, which, although weathered and faded, had once been painted in the colors of the rainbow. John recognized the architecture as being Scandinavian and was nearly too fascinated by it to cross.

“There are descriptions of a ‘Rainbow Bridge’ in some of the writings related to the Eddas,” he said excitedly. “I wonder if this has any relation to those?”

“It’s entirely possible,” Bert said. “Stellan’s specialty was Norse mythology, and there are several islands in the Archipelago that have deep roots in the Eddaic stories.”

“I say,” Charles commented, “wasn’t the original compiler of the Norse stories, Snorri Sturluson, one of our predecessors?”

A quick check in the endpapers of the

Imaginarium Geographica

showed that Charles was correct: the thirteenth-century scholar had indeed been a Caretaker.

“Amazing,” said John. “I wonder if Sturluson ever came to the Underneath, then? There were tales about the great serpent—a

dragon, basically—that stood guard at the roots of the world-tree, Yggdrasil. That bears a great similarity to the story about the Golden Fleece and the dragon that guarded it.”

“Maybe there were clues in the Eddas that can help resolve this,” suggested Charles. “What happened to the dragon and the tree?”

“According to the myth, the dragon was slain, the tree felled, and the world died in fire and ice,” Bert replied.

“Oh, well,” said Charles. “Never mind, then.”

The bridge, while old, was sturdy and stable, and they were able to traverse it in a matter of minutes. What they found on the other side John immediately named an “ur-forest.” A first-growth, dawn-of-man forest, with trees of such immense stature that every other forest in the world might have been only an image reflected in a child’s looking glass.

It was dark, foreboding. And there was only one apparent path to take, directly through the center of the island.

“Oh!” Laura Glue exclaimed. “I almost f’rgot!”

She hastily unpacked her bundle and instructed the others to do the same. Inside were red cloaks with hoods, which she explained must be worn before they could enter the forest.

“It’s part of the Law of the Forest,” she said, fumbling with the tie strings.

“She’s right,” John said, flipping through pages in the History. “There’s a caution here in ancient Greek, and it mentions the red hoods. It relates to some Spartan legends, apparently, and refers to the red hoods as ‘shields.’”

“Humph,” said Charles, who had wrapped the thin red cloth around his shoulders and was now helping Laura Glue with her

own hood. “It doesn’t seem sturdy enough to protect us from a drizzle of rain, much less shield us from anything.”

Jack was scowling and examining his hood with a look of distaste. “This is a girl’s color,” he complained. “Don’t we have one in green? Green would be best, but I’d even settle for blue.”

Laura Glue shook her head. “Red is the Law color,” she insisted. “No other color will work.”

John, again consulting the History, concurred. Jack muttered a few more words of protest, but nevertheless did as he was asked. He draped the cloak halfheartedly over one shoulder and fastened the ties with a slipknot.

“All set?” Bert said, examining the others. “Then into the woods we go.”

The children, that is, Jack and Laura Glue, wanted to take the lead, but Aven wouldn’t hear of it. She scouted the path about twenty paces ahead of the rest of them, followed by Jack, Laura Glue, and Charles, with John and Bert bringing up the rear.

As they walked, none of them noticed that they were being watched from high within the canopy above, and by more than one set of eyes. They were focused on the path, which for all practical purposes neatly bisected the island. The path was uncluttered and had once been neatly lined with golden cobblestones, but most had been worn down with use and age, and only traces remained of the yellowish pigment they once bore.

Every little while they would find a spot that had been clear-cut, all the lumber having been taken out long before. There was no obvious evidence of the woodsmen who had cut the timber, save for something Charles glanced out of the corner of his eye. It

was what seemed to be a figure of human proportions, some distance into the wood, away from the path. Statuelike, the figure’s arms were upraised as if it had been frozen midswing and then had the ax taken from its hands.

Charles thought he caught a flash of metal underneath the vines that had grown up around the figure, strangling it from view, leaving little exposed except for the rictus of terror frozen permanently on its face.

None of the others had seen it, and Charles saw no benefit in pointing it out, so they moved on.

“The principal use of the History,” John was explaining to Bert, “seems to have been to equip travelers against whatever dangers there were on the islands. And it always uses stories as examples, like parables.”

He thumbed through several pages, and then stopped. Near the back was a section that seemed to have been ripped out.

“Maybe that’s why Daedalus dismissed any talk of the ninth island,” said Bert. “He had no reference materials addressing it—or the dangers that we might encounter.”

“Or maybe he knew they were ripped out,” suggested John, “and chose not to tell us.”

“Quiet!” Aven whispered, holding her hands out to her sides. “Don’t speak. Don’t move.

“We’re being tracked.”

Slowly, carefully, Aven indicated with a slight nod of her head the dark masses up ahead that the companions realized were living creatures. Up ahead, coming closer, and, they realized with mounting horror, also coming up the trail behind them.

They were wolves.

Massive, shaggy behemoths that stood as tall as racehorses, and carried the bulk of bulls.

The wolves moved out of the trees, silent as a child’s prayer. They did not look at the companions directly but slowly moved in widening circles until they had surrounded the small party completely.

There was nowhere to run. And there was no possibility of combat. The companions were clearly outmatched.

“You wear the Hoods,” growled the graying wolf they all assumed to be the leader. “The Hoods of Law.”

“Yes,” Laura Glue said, emboldened by the creature’s ability to speak and, seemingly, reason. “They are the right color, so you have to leave us be, growly wolf.”

The wolf stared at her for a moment, then made a raspy chuffing noise and swayed its head from side to side.

The great creature, they realized, was

laughing

.

“Little Daughter of Eve,” said the wolf, “I am Carthos Mors, and I obey the Law of Centrum Terrae, set down lo these many years between my great-great-grandsire and thine own ancestor, the Queen of Sorrows. You wear the Hoods. You bear the color. And we are sworn to protect thee.”

As he spoke, Jack was hastily repositioning his cloak to cover himself as much as possible. Charles placed a steadying hand on his friend’s shoulder, and John and Bert drew up more closely behind Laura Glue.

“Protect us?” said Aven. “Protect us from what?”

The other wolves had already begun to growl, raised their hackles, and looked skyward. The answer to Aven’s question was above, in the trees.

The silence of the forest canopy was suddenly broken by a fierce chittering sound, as the huge winged monkeys dropped from the treetops where they had been tracking the companions’ progress.

Snarling, Carthos Mors and the other wolves leaped to the attack, and the companions fled for cover.

Shouting, Aven directed the others to the remnants of a structure that was thirty or forty yards off the path. It had once been a house but had long ago been burned, and all that remained were the foundations and a few charred trusses. There was also a great stone fireplace and chimney, which Aven herded Jack and Laura Glue into, drawing her long knife as she did so.

John and Charles handed Bert the

Geographica

and the History, picked up stout branches, and took up defensive stances alongside Aven.

Laura Glue was more awed than frightened by the spectacle taking place before them. Jack, for his part, was thrilled, and only slightly distracted by the fact that their hiding place smelled strongly of burnt gingerbread.

From their vantage point, the companions were able to see the fierce battle. The monkeys were roughly the same size as the children, with wings that were broader than the men were tall. Their teeth gleamed, and their claws slashed out wickedly at the defending wolves. And most fearsome of all was the fact that the monkeys’ eyes glittered with a fierce, feral, almost evil intelligence.

Carthos Mors and the other wolves took up a V-shaped formation that kept rotating fresh wolves to the front of the battle—which meant that only the thick ruffs of their backs were exposed to the cutting, slashing claws of the monkeys.

The monkeys’ ability to fly gave them a huge advantage—in a surprise dropping attack. But for sustained combat, against an organized opponent, it was soon clear they were outmatched. After a few minutes of fighting, the monkeys shrieked their dismay and abandoned the effort. In moments they had disappeared into the tops of the trees.

After assuring themselves that it was safe to break formation, the wolves dispersed into the shadows, except for Carthos Mors, who approached the companions. To their surprise, he again addressed Laura Glue, as if she were their natural leader.

“Daughter of Eve,” the great wolf began, “thou should have no further fear from thine enemies. We have honored the Law. What else might we do for thee?”

“We got to cross your island and go to the next one,” Laura Glue said. “We’re supposed t’ follow the path.”

“Then we shall guide and protect thee,” said Carthos Mors, bowing. Without another word, the wolf turned and began to walk down the path. Laura Glue followed him first, then the others, albeit a bit more reluctantly.

In the undergrowth, the companions could see the shapes of the other wolves, pacing them, protecting them.

Charles and Bert could not resist casting fearful glances at the sky now and again, but the monkeys did not reappear.

Inside of an hour, they exited the forest and found a well-crafted dock with a broad raft, and a cable strung overhead to guide the raft across the water to the neighboring island.

Carthos Mors bowed again, this time to each of them in turn before facing Laura Glue. She laughed and scratched the scruff of his neck. The wolf hesitated, then licked her, once, with a great

pink sandpaper tongue.

“Fare thee well, Daughter of Eve,” he said before disappearing into the trees.

Moving onto the raft, the companions unfastened the moorings and quickly moved away from Centrum Terrae.

Crossing to the next island was much less stressful than the crossing from Haven had been, or even the crossing from Croatoan Island to Haven. As Daedalus had said, the tides had indeed receded, leaving only a shallow track of water to guide the raft through. It beached some distance out from the approaching dock, and the companions were easily able to cross the rough, pebbled ground to the Hooloomooloo.

The pirate island existed in the same geographic space as the other islands they’d seen, but instead of being illuminated by the wan, omnipresent light from above, Hooloomooloo seemed mired in perpetual twilight.

There were wisps of fog drifting about, grazing at the edges of buildings before moving on to other pastures.

The entire island was built up in a shantytown of shacks and taverns. Every inch of arable ground was covered in hastily constructed buildings that looked as if they might collapse in a stiff wind. There were rings of docks lining the visible shoreline, and surprisingly, they were filled with ships.

Whatever or whoever had torched the ships of the Archipelago had obviously not done so here.

“Remember Daedalus’s warning,” Bert cautioned. “He said to skirt the island and avoid any contact with the inhabitants, if we can.”

Moving under cover of the fog and mist, the companions kept close to the docks, with the expectation of using the bulk of the ships for hiding places if they encountered anyone. But they never did.

There were a number of cats mewling about the docks, fighting over scraps of fish and offal and proclaiming their love for one another in screechy sonnets sung from fence tops, but those were the only living creatures they saw until they reached the far side of the island.

There, at a waypost, they found a single, solitary sentry. They would have taken pains to avoid him altogether, but the mists obscured their sight, and they were upon him before they had a chance to hide.

He was a pirate, grizzled, old, and garbed as they expected a pirate to be, with broad pantaloons, thick boots, a weathered captain’s coat, and a tricornered hat. He also wore a patch over one eye and waved at them as they approached.