The Search for the Red Dragon (20 page)

Read The Search for the Red Dragon Online

Authors: James A. Owen

It slowly dawned on John where the inventor was going with his story. “He used the panpipes, didn’t he?”

“Yes,” said Daedalus. “He went out into the world—to

your

world—and lured away children to become the playmates of Jason’s sons. To become Lost Boys themselves. This is the origin of the legends of children being lured from their beds in the middle of the night by soft strains of music that no adult seemed to hear. It wasn’t that they couldn’t hear it—but it was not meant

for them. And so the children simply disappeared, and no one knew to where.”

“Orpheus concealed himself well,” Bert huffed. “I know a great deal about the myths and legends of the world, and I’ve never before heard his name connected with the disappearing children.”

“Not as such,” said Daedalus. “But that was not the name by which the children knew him either. They had their own name for him, and fashioned their own mythology. And in the whispers under the covers, and in the dark corners of the room, the children knew that if you heard music in the night, it meant that the King of Crickets was coming for you.”

Bert paled, then sat heavily on the grass. “The King of Crickets,” he said, his voice trembling. “He…he’s a Pan?”

“Originally he was Orpheus,” Daedalus explained, “but after him, others assumed the office of the Pan, and the mythology about the King of Crickets followed them, too.

“Ulysses had two sons with the enchantress Circe, and one of them became the Pan for a time before leaving the Underneath. A few poets from your world, and at least one painter, have held the office. And there came a time when the Lost Boys took it on themselves to find their own playmates, and thereafter the Pan was not an adult, but a child.”

“And because of Echo’s Well, he never needed to age,” Charles concluded. “Ideal.”

“So children were enchanted and brought against their will?” said John. “I like that not at all.”

“Peter didn’t believe in it,” said Aven. “He believed that children should choose to come here if they wished, and not be forced

to become Lost. Orpheus trained him to use the pipes, as he had trained Peter’s predecessor, Puck, but Peter never used the pipes as the others had. He would find children and whisper to them in the night—and if they so chose, he would bring them here. But

never

against their will.

“Having seen the power of the panpipes, others among the Lost Boys—particularly Hugh and William—became uncomfortable with the idea that they could be compelled against their will to do anything. And so Peter came up with the idea of putting beeswax in their ears as a means of protection against the music. Because they were children, he even made a game of it.”

Aven lowered her head and swore softly as memories began to flood back to her. John and Charles exchanged knowing glances with Bert, and almost involuntarily they all looked at Jack, who was running gleefully through the apple orchard with the other children.

“It’s the first thing they learn here,” said Daedalus. “The children imagine that the King of Crickets is coming for them, and they all pack beeswax in their ears and hide among the trees and the rocks. Peter would designate a ‘safe’ base, and one by one, the children would make their way ‘home.’ The first one there would then take the wax from his ears and shout at the top of his lungs…”

“Olly Olly Oxen-Free,” John and Aven said together.

On hearing the words, all the children immediately stopped their games and crowed into the air.

“Hey!” Jack called out to John. “You win! Good show, John!”

“Peter saw being the Pan as a noble calling that would allow him to protect children,” Daedalus said, “so that what had hap

pened to Hugh and William would not happen to other children.”

“That’s quite an undertaking for a child,” Bert pointed out, “and a very mature point of view.”

“It is,” Daedalus agreed, “but then, Peter is an exceptional being. In all these centuries, he was the first to come here of his own free will, and the only child ever to discover the Underneath of his own accord.”

“I didn’t know that,” said Aven, “but I’m not surprised.”

Daedalus grinned with the memory. “It was he whom I first made wings for, to help him fly,” he said with no small pride. “His lame leg, remember? He had the spirit for it, and had done such a great thing in coming here, that I felt compelled to help him move as freely as the other children.”

“And after that, you just kept making wings for the Lost Boys,” said Bert.

“Well,” said Daedalus, “you know how children are. Once they saw what one of them had, they all wanted them.”

“Hey!” said Jack, running up to the companions. “Do I get to have a pair of wings too?”

Daedalus knelt down to look him in the eye. “That depends,” the inventor said. “Are you Lost?”

In answer, Jack merely laughed and ran back to the other children.

John folded his arms and turned to Charles. “I think someone has the panpipes,” he said. “That explains everything that’s happened: Peter’s caution with Laura Glue; the warning in Bacon’s History; and especially, the missing children. If someone were using the panpipes against the children, they’d be unable to resist.

And none of the adults would even know it was happening until it was too late.”

“Peter was the last to have them, and the only one now living who knew how to use them,” said Daedalus. “I can only assume he was taken when the children were, because we never found him—and he would not have gone willingly.”

“Could he have been entranced as well?” asked Charles. “Since the pipes affect children?”

“Not all children,” put in Charles. “Not if they had beeswax in their ears.”

John snapped his fingers. “That’s why the King of Crickets needed the Clockwork Men—to catch the children who couldn’t be compelled to follow the piping.”

“The children who couldn’t be compelled,” Bert said darkly. “

And

their leader.”

“Peter hasn’t been a child in years,” Daedalus said, looking askance at Aven. “He decided, finally, that it was time to grow up. And he’s never regretted that choice. He adores his daughter, called Alice Blue Bonnet, and even more so

her

daughter, Laura Glue.”

“Then he was taken by force,” stated Aven. “And his last act was to send Laura Glue for help.”

“Then we’ve got to help him,” said John, pounding a fist into his hand. “We must. And we have to start by finding the tunesmith who’s causing the trouble.”

“What are you thinking, John?” said Bert.

“I think if he can live for thousands of years,” John replied, motioning to Daedalus, “and also Hugh and William, then others from that time may have survived as well. And we know of

one trained to use the pipes, who had no issue with compelling children against their will.

“Orpheus. I think our adversary is Orpheus.”

HAPTER

E

IGHTEEN

Shadows of History

At Daedalus’s su estion,

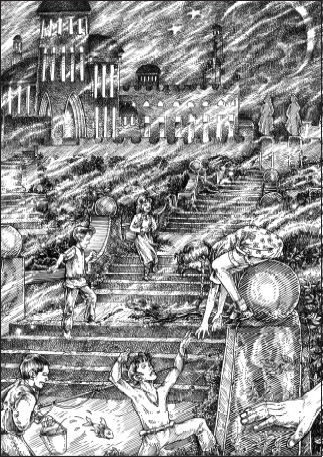

the companions and the Lost Boys left the orchard and returned to the more secure confines of Haven proper. The crenellated towers extended all around the orchard and gardens as well, but all of them felt an easing of tension at the idea of being within more closely built walls.

Jack had continued to evince further changes as a result of his transformation. It was as if he had forgotten being an adult, except when a point in the conversation required some arcane bit of knowledge that only he possessed. Then he rattled off details that made him seem exactly what he was: an Oxford professor in a ten-year-old boy’s body.

On the walk up the path, they again passed by Echo’s Well, where Daedalus asked John and Charles if they wouldn’t like to reconsider, now that they’d seen that no harm had come to Jack.

“Thank you, no,” said John. “I think one of us having the perspective of a child is enough.”

“But as you can clearly see,” Daedalus persisted, “he’s lost none of his ability to reason, and none of his education. It’s simply being filtered through a more youthful point of view.”

The crenellated towers extended all around the orchard and gardens…

“Sorry,” John said again, exchanging a puzzled glance with a slightly concerned Bert. “I think I can keep my focus better as an, ah, Longbeard.”

“Same here,” Charles answered when the inventor posed the question to him. “I might like to return sometime, once the crisis has passed, and give it a go—but not this time around, I’m afraid.”

“As you wish,” Daedalus said, with the faintest of tension in his jaw. “I only thought it might help. There are still many questions to be answered.”

“Agreed,” said John. “Foremost among them is this: Why weren’t all the children taken?”

Daedalus stopped and turned to him. “What do you mean?”

John indicated the children skipping around them in odd, loopy circles. “Pelvis Parsley. Meggie Tree-and-Leaf. Fred the Goat. All the children here. Why weren’t they taken with the others?”

“Perhaps they had beeswax in their ears, like Laura Glue,” Charles suggested.

“No,” said Bert. “She told us the Clockwork Men came for them, remember? The beeswax would have protected them from the panpipes, but not from Clockworks.”

“Oh,” said Charles, crestfallen.

“Is there anything special about the children who were left here?” John asked Daedalus. “In the Archipelago, none were left. They were all taken. So for these children to have been left behind, there had to be something setting them apart.”

Daedalus considered that a moment. “I cannot say. Perhaps the enemy had what they came for—Peter.”

“That doesn’t fit,” argued Aven. “It isn’t consistent with everything else we’ve seen.”

“I agree,” John said. “We…” He stopped and turned around. “Charles?” John asked. “What is it?”

The lanky editor had stopped walking and was standing about twenty feet back on the path. He was staring at the playing children with an odd look on his face.

“Charles?” said Bert. “What’s wrong?”

“Oh, I don’t think anything’s wrong,” said Charles, not taking his eyes from the children. “But has anyone noticed,” he continued in a trembling voice, “that Jack is sporting an extra shadow?”

The others stared. Charles was right. When Jack darted around a large stone bench, playing Monster and the Frogs with the other children, his shadow followed as a shadow should—and a second shadow followed an instant later.

John craned his head around to look for another light source. “There’s probably a very simple explanation, Charles,” he said with the beginnings of a smile. “In our last outing together, Jack was the one who gave up his shadow. I hardly think he’d overcompensate by adding a new one this time.”

“It’s not a second light casting it,” noted Bert, “or else all the children would have two shadows.”

He was right. The other Lost Boys were playing in the same area, but only Jack had twin shadows.

Aven summoned him over, and he ran to the companions, panting.

“That was quick,” said Charles.

“I was tagged out anyway,” said Jack. “Do you want to play with me, Poppy?”

At the mention of her old Nether Land name, Aven blushed. “No thank you, Jack. When did you get the extra shadow?”

Jack looked at her and blinked, then looked behind him, turning around like a dog trying to catch its tail. “Oh, that?” he said, as if she’d asked him why he had two ears or a nose. “It began to follow me after I spoke into the Well.”

“What do you think it wants?” asked John.

“Easy-peasy,” said Jack. “It wants me to follow it.”

“Follow it?” Daedalus said, surprised. “Why didn’t you mention it sooner, Jack?”

“Because,” Jack said, rolling his eyes in exasperation, “I wasn’t

out

yet.”

The companions retired back to Daedalus’s workshop, bringing Jack with them. Of all the Lost Boys, only Laura Glue chose to come as well, rather than go to sleep.

“I don’t need to sleep too often, ’cept after long flights,” she said. “And my grandfather always said, ‘He can sleep when he’s dead.’ I’m not sure what that means, but if it’s all the same, I’d rather stay with you.”

“Of course, dear girl,” Charles said, taking her hand. “We wouldn’t feel safe without our good-luck charm.”

Jack’s extra shadow continued to dart about at odd moments, as if it wasn’t quite comfortable being attached to someone with a shadow already in residence. It didn’t react when Bert or John tried to touch it, but it swiveled around completely when Daedalus tried to touch it as well.

“Hmm,” the inventor sniffed. “I don’t know if I should be insulted or not, that I repulse a shadow.”

“Where does it want you to go?” John asked when they’d gotten settled into the chairs at the workshop.

“West,” said Jack. “I’m pretty sure it’s west. It’s very curious,” he added, stroking his arms in wonder. “It’s a bit like the chill you might get when a ghost enters a room, except it isn’t cold—it’s warm. Very warm.”

“What do you think?” Bert asked Daedalus, who had busied himself checking his cauldrons. “Is it a good omen or bad?”

“I don’t think it’s an omen at all,” the inventor replied. “I think it’s another message. And it’s one that should not be ignored. To sever one’s shadow is not a task for the faint of heart. If it is gone too long from the body, one could weaken, even die. So for someone to send it, here, now, to Jack—they must want to guide you somewhere very, very badly.”

“What lies west of Haven?” John asked.

Daedalus turned, face lit by the vapors from his cauldron fires. “The rest of the Underneath. The path of Ulysses, and Dante, and Jason. And maybe…just maybe, the answers you are seeking, Caveo Principia.”

The inventor handed John the book he’d read from earlier, there in the workshop.

“This is a History written by one of your predecessors,” said Daedalus. “One of the oldest. It was written by Homer’s son-in-law, the poet Stasinus, thousands of years ago, and it contains what you will need to know about traversing the districts of the Underneath.

“The primary name of these lands is Autunno, which refers to everything found here, but each of the individual islands has its own obstacles and oppositions to overcome.

“The tidal forces here can be immense, as you saw crossing from Croatoan Island,” Daedalus went on. “The inhabited outer

lands of the first district are not themselves a true archipelago of islands, but the high ground that exists during the tide. When it’s out, we can go anywhere we like—but when it comes in, as you’ve seen, it becomes impassable.”

“Impossible?” asked John.

“Impassable,” repeated Daedalus. “Others who have traveled here saw the tides as a river. Some called it the Styx, others, the river Lethe. Names have come and gone, but the tides remain.”

“We say Atlas is shrugging,” said Laura Glue.

“I wouldn’t blame him a bit if he did,” Charles said.

“At any rate,” Daedalus continued, “the tides here do not shift with the moon, as they do in your world. They move by the calendar, each day. So when morning comes, they will go out again….”

“And Burton and the Croatoans will be able to cross,” said Bert. “Understood. We must leave before then.”

“Croatoan Island and the land Haven stands upon comprise the first district,” said Daedalus. “The second consists of the isle of Centrum Terrae, which is a kingdom of lakes and black forests. It has been the province of witches and sorceresses, now abandoned, but great beasts still roam there. Be cautious, and heed the History’s warnings.

“Also in the second district is the pirates’ island of Hooloomooloo,” said Daedalus. “It must be traversed to reach the next district, but skirt the perimeter and avoid meeting any of the inhabitants if you can.

“In the third district you will find but a single isle—Lixus, the island of automatons. If you move through it quickly, there should be nothing to fear on Lixus.”

At this, John and Charles exchanged curious glances, both of them thinking the same thing: automatons? As in Clockwork Men?

Charles began to say something but was silenced by a slight shake of John’s head. Something was not quite right here. John just couldn’t yet put his finger on what it was.

“The fourth district,” Daedalus continued, “is also comprised of a single land—Falun, the Great Pit. In truth, it is less an island than a great rending in the earth, where ores are mined to provide the raw materials for the inhabitants of Lixus. You must go straight through the center. But be wary, for the way is filled with more perils than those physical.

“The fifth district contains the seventh and eighth lands. First is Aiaia…”

“Circe’s island,” stated Charles. “From the

Odyssey

.”

“The same,” Daedalus said with a hint of surprise. “If you know that much, you should already know of the dangers you may face there.

“Just apart from Aiaia are the Wandering Isles, which are the only other islands past the second district that are fully inhabited. The original settlers were Greek refugees, but centuries later a company of travelers seeking refuge from the Black Plague also came there during your Middle Ages.

“They greet wanderers as fellow travelers, and those with the ability to tell stories are accorded great benefits, much as if they were visiting royalty.”

“So,” John concluded, “if we can get through witches, pirates, mechanical men, the Great Pit, and Circe, we’ll end up at a place where we will be honored for our storytelling. Grand, that.”

“Look at it this way,” said Bert. “After all that, we’ll have no

shortage of tales to tell.”

“You’ve told us there were eight lands,” said Charles. “But there was another indicated on our map of Autunno. What of the ninth land?”

Daedalus closed the book and shook his head. “I don’t think you’ll be going that far. What you search for is most likely found within the closer lands. To go farther is not something many before you have done, and I would not advise it now.”

“I suppose you can make that decision later on,” said Charles, “if circumstances warrant.”

“I won’t be going with you,” Daedalus said with a curious halting in his voice. “At present, I cannot leave my experiments.”

“Hah,” Aven snorted. “That’s a crock. Most of the children of Haven are missing too, or hadn’t you noticed?”

“I…have other responsibilities, which require that I stay here on Haven,” said Daedalus. “I am truly sorry.”

Bert frowned, and Aven drew in a sharp breath, but John and Charles merely thanked the inventor for the book and the wise counsel.

Daedalus and Laura Glue went to a large storeroom and assembled some of the supplies the companions would need for the journey, while Jack remained with the others.

“I’m not sure I trust him entirely,” John murmured. “Something’s afoot.”

“Nonsense,” Aven said. “He’s Daedalus—he’s been a friend and protector to the Lost Boys for as long as I can remember. I trust him completely.”

“I’m not certain either, daughter,” said Bert.

“Why?”