The Road to Ubar (18 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clapp

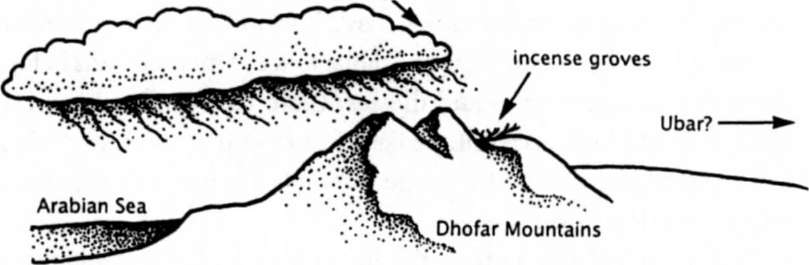

Classical Greek and Roman civilizations were well aware of Dhofar's coastal mountains, snakes and all, for they blocked the way to Arabia's fabled incense groves. These mountains were, in fact, almost certainly "Sephar, the eastern mountain range" that in Genesis 10:30 was taken to mark the edge of the known world. Throughout history, this escarpment had guarded a land stubbornly and persistently unknown, the heartland, we hoped, of our People of'Ad.

While investigating the well of the Oracle of 'Ad, we had visitors, tribesmen who drifted down from the mountains. Their bearing was elegant; their hair, done up in fine braids and tinted blue, had the fragrance of frankincense. Members of the Shahra tribe, they spoke, in addition to Arabic, their own peculiar chirping, singsong language, called by early explorers "the language of birds."

4

They confirmed that, indeed, the well was still known as a well of the People of 'Ad ... and one of their number, speaking in crisp, Cambridge-accented English, matter-of-factly told us, "

You know, we are the People of 'Ad.

" His name was Ali Achmed Mahash al-Shahri, and where he would take us provided a major breakthough.

Like generations of Shahra before him, Ali Achmed was born and raised in the Dhofar Mountains. But as a young man he left his homeland to join the Trucial Oman Scouts, a military force that patrolled what was once a British protectorate in eastern Arabia. Commissioned as an officer, he was sent for further training to England. There he was surprised by the regard people had for traces and fragments of the distant past and by the great museums of London, Oxford, and Cambridge, built to house these artifacts. Ali Achmed realized that his people, the Shahra, had their own legacy: ancient writings hidden in the mountains of his childhood.

After mustering out of the Trucial Oman Scouts, Ali Achmed returned home. He sought out and hand-copied these pictographs, then acquired a Nikon 35-millimeter camera, taught himself how to use it, and went on to describe, document, and map dozens of sites.

Now he asked, could he show them to us?

With Ali Achmed as our guide, we drove up and over the steep sea-facing side of the Dhofar Mountains, emerging on a rolling, pastoral tableland. We passed Shahra herdsmen pasturing their small, short-horned cattle, the only cattle in all Arabia. Threading our way through a maze of tracks, we came to the mouth of a rugged and thankfully shady canyon. Even in December, the temperature was close to 100 degrees. On foot, we hiked on until we saw above us, on the canyon's south wall, a wide, shallow cave.

"You seek evidence of the People of 'Ad?" Ali Achmed asked. "Please, have a look."

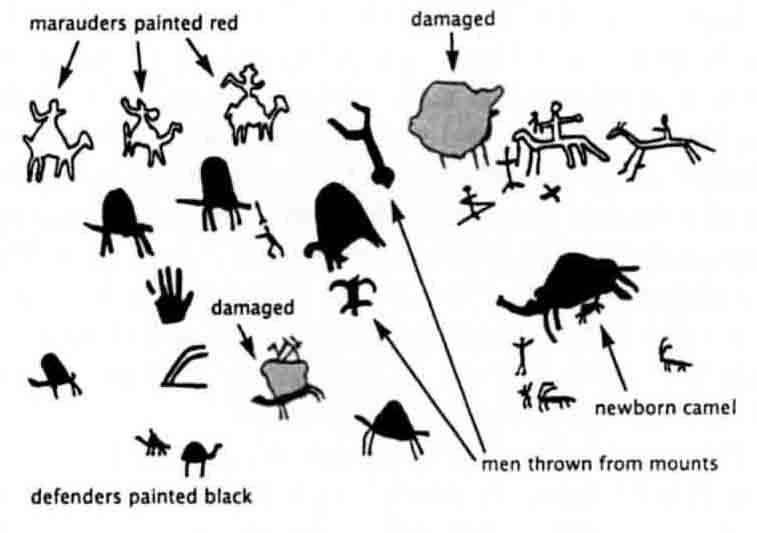

After climbing up to the cave, we could see that its back wall was covered with hundreds of pictographs drawn in red and black pigment. Long ago, Ali Achmed explained, caravans had paused here and left their mark. He pointed out where someone had recorded the scene of a wolf attacking an ibex. Farther up on the cave's wall were three figures that looked likeâbut were notâthe biblical Three Kings. Ali Achmed thought they were more likely three bandits, part of a group marauding an incense caravan.

Pictograph of wolf attacking ibex

Pictograph of attack on a caravan

What excited Ali was that in the cave were not only pictographs but written inscriptions. Here was evidence that his ancestors not only traded in incense but were literate and civilized. (By definition, a civilization is a society with a written language.) Making sense of these meandering lines was problematicâa challenge beyond us.

Inscription in Dhofar cave

Many of the letters in these inscriptions related to letters in ESA, the Epigraphic South Arabic alphabet we had encountered on the coast at Sumhuram. But these mountain inscriptions contained eight

additional

letters, and it was anyone's guess how they were sounded or what they meant. Ali Achmed thought they might correspond to the eight sounds in the Shahra language beyond the twenty-eight sounds of classical Arabic. He pronounced them for us. They sounded something like "

sh'a, jh'a, je', k'e, ka', th', k'a, le'

"âcurious, almost birdlike sounds, springing from the back of the throat. Sounds of Arabia long ago. Ali Achmed said, "Nobody can pronounce them but the people of our mountains."

At the far end of the cave, Ali pointed out a pictographic map that charted routes leading on to where, in antiquity, "silver" frankincenseâthe finest varietyâgrew wild and was harvested, as it still is. Ali Achmed showed us where.

A few days later we watched a band of little children dancing along behind two tribesmenâone wiry, one corpulentâas they crossed an arid valley and approached a scattering of scraggly trees with reddish bark. Bent and twisted, many of the trees were only waist high. Yet their resin, or sap, was once as valuable as gold. They were frankincense trees, found where the mountains of Dhofar gave way to the great interior desert of Arabia.

5

The wiry man's craggy face was framed by a handsome white beard and a black turban. He wore a saronglike garment with a traditional silver dagger at his waist, complemented by a recent-issue assault rifle slung over his shoulder. Approaching a frankincense tree, he noisily exhaled, then chanted: "Ab st't d'h'la fe lh'ya!" (Exhale!) "A1 as'r m'sly 1'yo tr'le'ha!" (Exhale!)...His age-old song of harvest had a driving, intense rhythm, punctuated by strange, percussive exhalations.

Moving in time to his song, the wiry tribesman slashed bits of bark from the tree. A few yards away his partnerâa

pashalike

fellow topped by a large red turbanâmirrored his movements. The little children ran from one man to the other as, giggling and laughing, they played tag in groves of antiquity.

The Roman historian Pliny the Elder (23â79

A.D.

) relates that these frankincense groves were inaccessible and that the southern Arabiansâour People of 'Adâdid not encourage visitors. In addition to tales of flying serpents (quite true), the 'Ad appear to have propagated stories of deadly vapors arising from the punctured trees (not so true). Not surprisingly, Pliny tells us that "no Latin writer so far as I know has described the appearance of this tree." Nevertheless, he learned that "the district ... is rendered inaccessible by rocks on every side, while it is bounded on the right by the sea, from which it is shut out by cliffs of tremendous height. The forests extend twenty

schoeni

[about five miles] in length and half that distance in breadth ... In this district some fifty hills take their rise, and the trees, which spring up spontaneously, run downward along the declivities to the plains."

That was as we found it: the finest trees, those that produced silver frankincense, were confined to a surprisingly small area and were wild. They stubbornly resisted cultivation. Pliny further informs us:

Cross-section of Dhofar Mountains

It is the people who originated the trade, and no other people among the Arabians, that behold the incense-tree; and, indeed, not current extent of monsoon all of them, for it is said that there are not more than three thousand families which have a right to claim that privilege, by virtue of hereditary succession; and that for this reason those persons are called sacred, and are not allowed, while pruning the trees or gathering the harvest, to receive any pollution, either by intercourse with women, or coming in contact with the dead; in this way the price of the commodity is increased owing to the scruples of religion.

6

This holy harvest of frankincense, some scholars feel, was a convenient fiction, an invention of southern Arabians intent on hoodwinking credulous customers. Yet we were inclined to believe Pliny's account. There was something very serious, almost formalized, in the way our two tribesmen moved from tree to tree to the rhythm of a measured chant.

The chant ended with a loud exhalation. The tribesmen and the children drifted off across their land, a moonscape dotted by small groves of frankincense. The shouts and distant laughter of the children dissolved into a desert breeze, which now bore the piny, slightly raw scent of freshly cut frankincense. Each slash in a tree's bark produced a dozen or so thick white globules of resin. Slowly these globules would lose their milky opacity and gain a silvery translucence as the frankincense hardened and crystallized. Fifteen days hence, the men would return to scrape it into special shallow baskets. Though a portion of the harvest would be kept for their own use, most of it would be traded to the coast. It would be used to sweeten the air of households throughout Arabia, to scent men's beards before dining, to fumigate robes and dresses. Little kids would chew it as gum. It would be a prized ingredient in exotic perfumes, including the French-Omani scent Amouage, promoted as the most expensive fragrance in the world.

That we might see more of the living history of the highlands of Dhofar, Ali Achmed invited us to visit a remote Shahra settlement. Driving by night, we arrived at dawn at a compound of four thatched huts clustered around a brushwood corral. Three of the huts sheltered cattle; the fourth was home to an extended family. Though the hut was windowless, two doors let in sufficient light to illuminate the single large room. Its walls and domed ceiling were woven of twisted, blackened tree trunks and branches, the best wood to be had in an arid land. Two young girls were rolling up sleeping mats. A baby was squalling in the corner. Two older men and a woman crouched by an open fire, making their preparations for the day, a day measured by the burning of frankincense.

Though the woman wore a long, hooded black dress, she was unveiled. A gold ring pierced her nose, her eyes shone with self-assurance. She was the settlement's matriarch. With brass tongs she picked embers from the fire and placed them in a brightly painted clay incense burner shaped like a horned altar. Then she added crystals of frankincense, which glowed brightly and immediately gave rise to a fragrant, smoky plume. All the while she chattered with the two men in the Shahra's strange "language of birds."

"Incense is most pleasing to God," she said, adding more crystals.