The Road to Ubar (17 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clapp

Our police escorts saw us off. And one, Jumma al-Mashayki, had a last question for George Hedges. Throughout our reconnaissance George had relished consulting his pocket Arabic phrase book and constructing new and varied greetings, improvements on the usual "sabah al-heir" (good morning) or "khef halek?" (what's up?). Recently, though, George's greetings had elicited looks of distinct puzzlement.

Jumma was compelled to ask, "We policemen have all been wondering, Mr. George. Why, over the past few days, when you meet someone, why do you shake their hand and tell them, 'I am firewood'?"

Back in Los Angeles, Firewood, Ron Blom, Kay, and I reviewed the trip. It hadn't exactly been a disaster, yet it was well short of being a resounding success. The People of 'Ad and their lost city were proving to be surprisingly elusive. Though we had been reasonably frank about this with our sponsors in Oman, they didn't seem to mind, and looked forward to our return in the late fall. In the interval Ron Blom would have a chance to fill in gaps in our space imaging. In England, Ran Fiennes would plan and arrange the logistics of our next venture.

But then, five days after our return home, headlines announced: "

IRAQ INVADES KUWAIT. SAUDI ARABIA THREATEN E D.

" A war was on, a war that could well involve all of Arabia. The next day brought reports of Iraqi fighters dispatched to Yemen, where they were poised within striking distance of the Omani Air Force base that we had helicoptered into and out of the week before. We called and faxed our Omani contacts and friends to wish them well in the coming war. They thanked us and sincerely regretted that for the foreseeable future an expedition in search of Ubar would be out of the question.

W

E PUSHED OUR PLANS BACK

a year and hoped that when the time came we could still round up our original Ubar team. By winter the tide of the Gulf War had dramatically turned; Operation Desert Storm drove the Iraqis from Kuwait. In June 1991, Ran and Ceorge received word that we would be welcome to return to Oman, though parts of the Rub' al-Khali would be off limits. Also the Omanis reminded us that they expected the expedition to be filmed, which was fine by me, for that is what I do.

But who would pay for such a film? After our reconnaissance, we honestly had to admit that the odds were strongly against our finding Ubar. That was not the only problem. A Turner Entertainment executive had read our film proposal and decided "too much sand" (so that's what was wrong with

Lawrence of Arabia!

). National Geographic had already thought the expedition "too dangerous."

As our date of departure approached, George described the situation: "Everything is coming together, and we won't be able to shoot a foot of film." It was a Saturday morning, and George had stopped off to shoot a game or two of pool with his friend Miles Rosedale. Owner of the wholesale Rosedale Nursery, Miles was aware of our Ubar project and intrigued by the unique botanical properties of frankincense.

"A shame," Miles commented. "Five in the corner pocket." Clink-clump. As he eyed his next move, he asked, "Just what would a movie cost?"

A half hour later, George left with Miles's commitment to underwrite equipment rental, eighty cans of 16-millimeter color negative, and the hiring of a cameraman and soundman.

George Ollen, a longtime free-spirited acquaintance, agreed to take a break from surfing and learn how to operate a Nagra location sound recorder. For the position of cinematographer we had an application written on stationery that featured a photograph of a man with a skull balanced on top of his head. The letter concluded:

Remember: I happily hung off the side of a balloon on a rope, rode 2000 miles through the deserts of Egypt and the Sinai on the back of a Harley, rode 1100 miles on a raft down the Yangtze River,

ALL WITH A CAMERA IN MY HAND.

I'm bored with my day job and i'm ready to go. I even have a hat. Hope to hear from you soon.Yours, Kevin O'Brien

In the second week of November 1991, all of our original Ubar team, plus cameraman Kevin O'Brien and soundman George Ollen, were back in Oman, at Salalah, on the shore of the Arabian Sea. After a fifteen-month delay, we were anxious to pick up where we had left off. Before we set out in search of Ubar itself, we intended to explore the Dhofar coast and mountains for tangible evidence of the People of'Ad.

In 1329, Muhammad ibn Battuta, a traveler to the far reaches of the known world, visited these same shores and wrote that "half a day's journey east of Mansura [an old name for Salalah] is the abode of the 'Adites."

1

He was apparently referring to ruins encircling a great well that appears on Ptolemy's classic map of Arabia. There it is marked "Oraculum Dianum," the oracle of Diana, goddess of the hunt and the moon. (In reality, the site was probably dedicated to a southern Arabian equivalent of the Roman Diana.)

We had scouted this well during our first reconnaissance and found that it was called, even today, the Well of the Oracle of'Ad.

2

Hidden in a valley just beyond the coastal plain, it was a very impressive hole in the ground, a good fifty feet wide and no telling how deep. Was it dug by man, or was it a striking oddity of nature? Whatever it was, we guessed that over the centuries it had gradually filled with debris, debris that could contain artifacts dating to the time of the People of 'Ad. Ancient peoples were forever dropping coins, curses (written on scraps of lead), offerings, and even vanquished enemies (and their weapons, armor, and all) into wells.

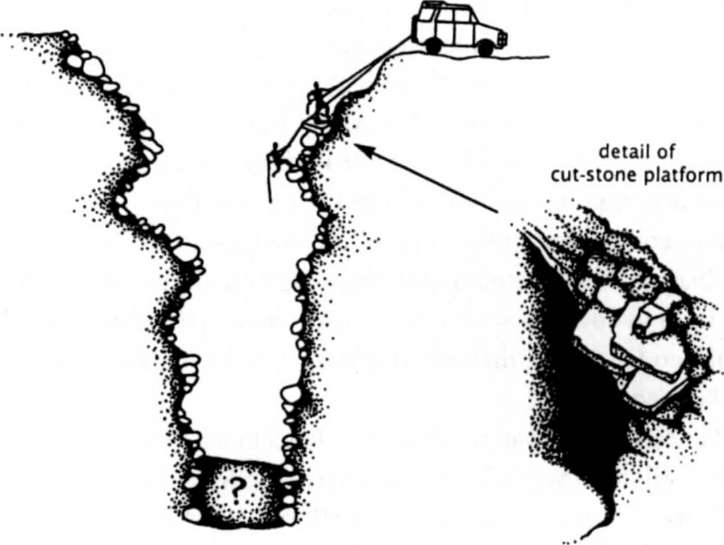

We backed a Land Rover Discovery as close as we dared to the rim of the well. Andy Dunsire, a stout, ruddy Scotsman, peered down it and muttered, "Daresay I doon like the look of that," then set about anchoring climbing ropes to the vehicle's rear bumper. Unique characters fetch up in the desert, and Andy was one of them, as were his associates Black Adder (Pete Eades) and Guru (Neal Barnes). They were engineers for Airwork, a British firm contracted to maintain Omani Air Force fighters, and one of our sponsors. As much as possible, Airwork would be giving Andy and his friends time off to help out with our expedition. Black Adder was fascinated by desert plants and flowers, Guru was a snake man, and Andy lived to explore desert caves and sinkholes, which made him just the fellow to lead the descent into the Well of the Oracle of'Ad.

On parallel ropes, Andy Dunsire and ex-SAS commando Ran Fiennes roped up and, side by side, rappelled down the well's initial sixty-degree slope. "Ran, mind your..."Andy cautioned. "Uh, never mind," he added as a sizable chunk of rock broke lose from under Ran's foot, bounced down the well, and landed with a sickening

thunk

far below.

Juri hovered at the rim of the well. "Keep going," he shouted down.

"Easy for you to say."

"Ran, right to your left. That flat rock there. Can you check it out?"

Twenty feet down the well, Andy and Ran maneuvered to either side of the rock Juri had pointed out and started clearing it with trowels and brushes.

"Looks man-made," Ran shouted up.

Within a few minutes, Andy and Ran had cleared off four blocks, part of what had once been a cut-stone platformâevidence that the well was more than a natural hole in the ground. Gingerly now, Andy and Ran eased over the platform and down into the well's narrowing vertical shaft. And hardly were they out of sight than they reappeared, pulling themselves up and out of the well.

"There's a bad overhang," Ran reported.

"And the walls. They're nothing but boulders stuck together with mud," Andy added.

Dropping deeper into the well, they agreed, would be courting disaster. The friction of the rappel ropes on the overhang could easily trigger a rock fall.

Well of the Oracle of'Ad

For the rest of the day, Juri directed us and a dozen Airwork volunteers in surveying, clearing, and digging to the west of the well. He traced what appeared to be the outline of a small temple, perhaps a ritual entryway to the oracular well of the People of 'Ad. How were the oracles delivered, we wondered? By a

halmat,

a "seeress of dreams," or by

istqsam,

divination by the drawing of marked arrows? Or, Juri suggested, oracles could have been shouted up by a priest hidden out of sight in the well, possibly on the platform that Andy and Ran had cleared.

To find out anything more, we would have to devise a way to get down into the well. Ran turned to Kay and said ingratiatingly, "Tomorrow, Kay, I've been thinking. Maybe you could find us a crane? Say a construction crane? A big one? It would be ever so kind of you to do that."

Early the next morning, we were enjoying a cup of tea at the edge of the well when Kay cleared her throat with a distinctly self-satisfied "ahem." We looked over at her; she nodded out across the desert, where a great yellow crane was lumbering toward us. She had contacted British Petroleum, which had already promised us 8,000 gallons of fuel. So, she reasoned, it would be only a minor addition to their sponsorship if they lent us one of those big cranes they used to construct pipelines and oil wells and things like that.

The crane crept to the edge of the well, and Ran and I donned hardhats and clambered into its waist-high clamshell scoop. Out we swung, and down we went into the great hole in the ground until we could no longer see the crane's operator, or he us. The walls of the well closed in.

Ran called on a walkie-talkie: "Go left a touch, left a touch."

Ron Blom answered, controlled panic edging his voice, "Okay, we'll try. But I can't guarantee anything. He doesn't really speak English. The crane man doesn't speak English."

"Try gesturing," said Ran, then cautioned, "You see, if we touch the walls at all, we'll bring the whole lot down. So you've got to be very, very careful."

On down we went, past the platform Ran and Andy had cleared the day before. As Ran radioed instructions, I imagined Ron, out of sight far above, translating our instructions into signals, hoping he wasn't bashing us into oblivion. Did pointing this way and that mean the same in Arabic as it did in English?

"Uh, is this safe?" I wondered aloud, forty feet down the well.

Peering down, Ran didn't answer.

"Ran??"

"We'll see ... we'll see," he replied, distracted by what lay below. "Strange place, this ... Twelve feet to go ... six ... two ... stop!" We jumped clear of the bucket.

The well was dry and would be ideal for excavation. Buried beneath our feet could be ancient offerings, clues to the identity of the People of'Ad. Then we looked up. Overhead, tons of boulders were poised to break loose from the walls of the well. We whispered, as if the sound of our voices might bring them crashing down.

"These look really precarious, this lot... The bottom of that area there, if one goes, the whole lot will go." He shook his head, then looked to his feet. "And we're not alone, I see."

They had momentarily sought refuge in the well's debris when we jumped from the bucket. But now they were everywhere: scorpions darting in and out of tumbled brush, trash, and animal skulls and bones.

Ran and I agreed that our brief descent was treacherous enough; to try to excavate the well would verge on the suicidal. Climbing back into our bucket, we radioed Ron Blom to haul us back to the surface, where everyone was quite naturally disappointed by our report of conditions below. We had our crane, enthusiastic volunteers, and, as part of our gear, a ground-penetrating radar rig that could image the depths of the well and spot potential artifacts. We had even discussed running lights down so that we could dig around the clock in shifts. But now the only sensible thing was to pack up and move on.

Kay had set up a supply tent near the well, and now, as we broke camp, one of our volunteers hefted a last crate of supplies. And froze. "Under the box! S-snake!"

Kay looked over, let out a distinct "Eeek!" then turned pale. She realized that in moving things about in the tent, she had beenâdozens of timesâwithin striking range of the creature now coiled in the dust.

"Get Guru!" the cry went up from our Airwork volunteers. Guru was never without his curved snake stick, which he now used to coax the snake in the tent into a large bottle. "Nasty creature," he noted as he capped the bottle with a perforated lid. "Carpet viper. Hemotoxic. Neurotoxic. Hits you and you turn black."

"Oh, yes?" said Kay.

"No known antidote," Guru continued. "Hits you and you're dead in twenty minutes."

"Then it's nice," said Kay, "that he's in your jar just now."

"Yes, it is," concurred Guru, patting the sweat from his forehead. "Deadliest snake in the world."

Curiously, there was a lesson to be learned from Kay's carpet viper. Several classical authors had reported that the incense groves of southern Arabia were "guarded by flying serpents." The natural historian Diodorus of Sicily wrote that "in the most fragrant forests is a multitude of snakes, the color of which is dark red, their length a span, and their bites altogether incurable; they bite by leaping upon their victim." The historian StTabo added that they "sprang as high as the thigh, and their bite is incurable."

3

Despite such warnings by Diodorus and Strabo, the presence of any snakes in this land had long been disputed; it had been suggested that the "flying serpents" were in reality infestations of locusts. Or that they were apparitions concocted by ancient locals to warn outsiders to keep their distance. No, we learned, the "flying serpents" were really flying serpents. The mountains of Dhofar were full of them; on another occasion we saw one coil and strike. Though the creature didn't become airborne, it was fully capable of Strabo's "high as the thigh."