The Road to Ubar (12 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clapp

This tale told in dusky medieval Cairo illustrates why the Ubar myth has survived for many a century. It is a good yarn, here related by a skilled and stirring storyteller.

On the lookout for Ubar clues, I was first intrigued by the choice of three clouds offered to the tale's rapidly sobering delegation of drunks (lines 140â145). I was aware that a three-way choice was a venerable Semitic theme; similar choices are described in the Bible and in accounts of Arabian soothsaying. But why are the three clouds white, then red, then black? The answer came in a flash of perception from JPL's Ron Blom.

"Tell you what it sounds like to me," he remarked over lunch at the lab's cafeteria, "sounds like a report of a volcanic eruption. First there's a cloud of white smoke, then comes a rain of red magma, and finally black ash falls. Like the old story says, 'ashes and lead.' But I don't recall any volcanoes where we're looking for Ubar."

There weren't any. Nor were three clouds mentioned in the Koran, the earliest coherent record of the Iram/Ubar story. What likely happened is that a report of an explosive volcanic eruptionâpossibly Vesuvius in 79 or 512

A.D.

âwas rung in for its dramatic value, as an effective way to set up the city's destruction.

As I further studied the tale, I found that the three clouds weren't the only elements slipped in after the fact. The running description of the travails of the prophet Hud, for instance, turned out to be based on the considerably later and unconnected experiences of the prophet Muhammad as he preached a new religion in Mecca and was spurned by his tribe.

It became evident that this tale of al-Kisai, on the surface relatively straightforward, had a complex subtext, highly symbolic and replete with allusions-within-allusions. (For a look at this subtext, see the Appendix,

[>]

.) Essentially, much of the tale is immensely intriguing but has little or nothing to do with Ubar as a real place. On the other hand, "The Prophet Hud" incorporates lore that may indeed bear on an actual city's rise and fall. The tale offers potential insights into Ubar's antiquity, its people, its destruction, and its location.

ANTIQUITY

Al-Kisai's tale is heralded by a genealogy (lines 1â3). Arab storytellers loved genealogies, for they imparted a ring of authenticity. They also harked back to a time before writing, when an individual and his tribe were defined by their place in a long and worthy procession of remembered ancestors. What is unusual is that by Arab standards, this genealogy's line of descent is remarkably short, with only a half-dozen generations between Noah and the glory days of Iram/Ubar. This would make the People of 'Ad an ancient tribe, perhaps the oldest in all Arabia.

PEOPLE

The People of 'Ad appear to have had a lively appreciation of sin, though the nature and extent of their sinfulness is unclear. They were certainly materialistic, and they worshipped at least three gods. Confronting them, the prophet Hud made quite an impact preaching the worship of but a single God. Who, then, was Hud?

In Semitic lore (shared by both Jews and Arabs), names frequently have an elemental allegorical meaning: for Daoud, or David, it is "beloved"; for Suleiman, or Solomon, it is "man of peace." And "Hud" comes from the root HWD: "to be Jewish." This linkage is clearly reflected in the Arabic of the Koran, where "Hud" is not just the name of a prophet but a collective noun denoting the Jews.

Was Hud Jewish?

He could well have been. Much has been written of the Jews of Arabia, much of it chronicling the period 300â525. In that era Jewish courtiers and even a Jewish king ruled the kingdom of Himyar, which rose and fell in what today is Yemen. It is no stretch of the imagination to believe that a Jewish traderâor even a rabbiâcould have made his way to Ubar and preached the religion of a single God.

Was Hud a historical figure? It is impossible to know. But he certainly was a compelling

allegorical

figure, a symbol of early monotheism. The monotheism of Arabia and Islam, the prophet Muhammad himself declared, was heir to revelations first made to the Jews.

DESTRUCTION

Iram/Ubar was suddenly destroyed by a great cataclysm. But what actually happened? The storyteller appears unsure of his apocalyptic imagery. Early on, a mysterious voice promises destruction by an "icy gale, turbulent with dust" (line 108). A few sentences later another voice exclaims, "May they [the 'Adites] quench their thirst with hot water" (line 115). Next we are given the imagery of the three volcanic clouds. The Barren Wind that is ultimately unleashed is supremely violent but not terribly convincing. It has the characteristics of a tornado, an all-but-unknown phenomenon in southern Arabia.

Other versions of the tale downplay the wind, having Iram/Ubar destroyed by a mighty but still baffling "Divine Shout." In one account the end comes as "suddenly the earth opened around it and Iram, bathed in a strange twilight, began to sink slowly down until the whole city was completely swallowed up. All that remained was an endless wilderness of empty, shifting sands across which the winds moaned and howled."

3

If we ever did find Iram/Ubar, it certainly would be interesting to investigate how (or even if) the settlement was destroyed.

LOCATION

The casual mention of the "Wadi al-Mughith" (line 147) was to provide a valuable clue to Ubar's location. At first the name didn't make any sense; it's not to be found on any map, old or new. But then, by chance, I found it cited in an account by the 800s

A.D.

geographer Ibn Sa'd, except that he expands the name to the "Wadi al-Mughith

in Sihr.

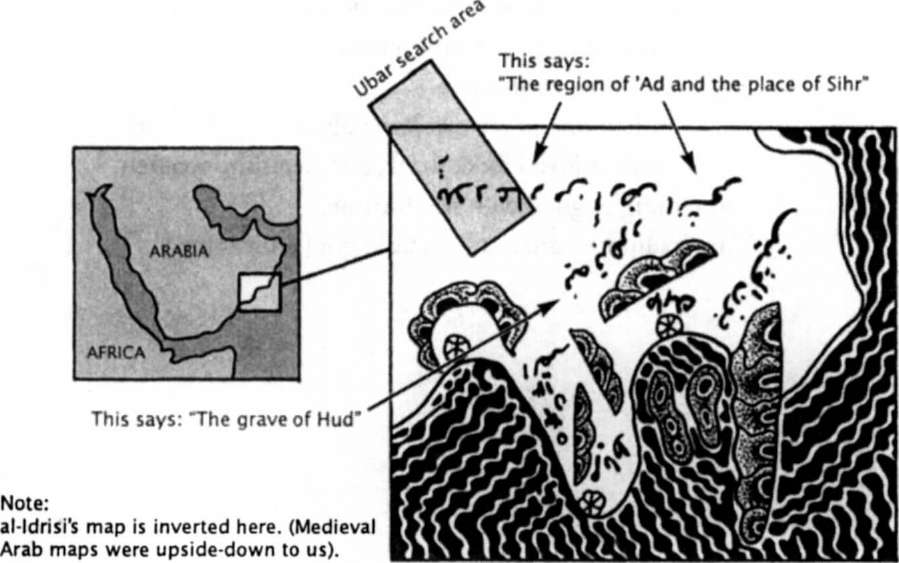

" This rang a bell from my earlier Ubar research. The word "Sihr" appears on something called "The Gardens of Humanity and the Amusement of the Soul," a map compiled by Muhammad al-Idrisi, an Arab cartographer living in Sicily in the 1100s

A.D.

Though fanciful in title, the map is an outstanding example of the Arab scholarship that through the Dark Ages kept a flickering flame of learning alive. Based on earlier records and the accounts of mariners and merchants, it depicts Arabia in detail. The Ubar region bears the legend "the region of 'Ad and the place of

Sihr.

"

Here, then, was an intriguing two-step connection: our rawi's tale placed Ubar near the Wadi al-Mughith, which another writer called the Wadi al-Mughith in

Sihr.

His addition of the word "Sihr" leads us to a locale on a respected early map of Arabia, a detail of which is shown here. The shaded box approximates what we had tentatively settled on as our Ubar search area. We were, it appeared, in the right neighborhood!

Detail of al-Idrisi's map of Arabia

Several worthies of storyteller al-Kisai's time locate Iram/Ubar and the People of 'Ad in the same patch of Arabia. The historian Nashwan ibn Sa'id al-Himyari (died 1117) sums up: "Ubar is ... the name of the land which belonged to 'Ad in the eastern part of Yemen; today it is an untrodden desert owing to the drying up of its water. There are to be found in it great buildings which the wind has smothered in sand." (At the time, eastern Yemen included part of what today is Oman.)

4

This Nashwan al-Himyari was also a poet, who dwelt on the theme of vainglory come to grief. His verses are an epitaph for Iram/Ubar and the People of'Ad:

8. Should You Eat Something That Talks to You?They turned to dust and are trampled under foot,

as they once did with others ...

They rest in the earth now,

when once they dwelt in palaces

and enjoyed food, drink, and beautiful women.

Time mingles good with bad fortune,

Time's children are made to taste grief amidst joy.

5

T

HE APPROACH

I

HAD TAKEN

with al-Kisai's tale "The Prophet Hud" was to look closely at the story, identify the elements added on over the years, and throw them out, hoping that maybeâalways maybeâsomething would be left of a real time and place. This approach also worked well with the story of the geographer Yaqut ibn 'Abdallah (died 1229). "Yaqut" was a slave's name meaning "Ruby." In the medieval Arab world, it was common to give slaves names of gems and flowers and virtues, allowing their master to say, "Bring me dates, Pleasure. Tell me a story, Ruby."

As a trusted slave, Yaqut traveled the Persian Gulf on behalf of his master, a Baghdad merchant. He increased his master's prosperity, traveled farther, and eventually was given leave to compile his Mu-

jam al-Buldam,

or "Dictionary of Lands." It includes a substantial section on the "City of Wabar," or Ubar. Featuring lore Yaqut gathered while trading in Oman, most of his description is fanciful. Yaqut was particularly taken by the notion of nisnases. He wrote, "The Lord destroyed everything there [in Ubar] and converted the human beings to nisnasâa monkey-like creature with a human-being look. The men and women appeared ridiculous, each had half a head and half a face with only one eye and one arm and one leg ... They used to jump high and rapidly on that one leg. God made them chew up the grass like cows and buffalos."

1

Yaqut gives us anecdotal accounts of bedouin run-ins with "devil man" nisnasesâand he is disquieted by the fact that nisnases speak Arabic. This, he reports, troubled the bedouin as well, who felt it was okay to hunt down and spear a nisnas (just as they would slay any other creature), but, they asked, should you eat something that talked to you?

Because of his preoccupation with nisnases, both Arabic and Western scholars have ridiculed and discounted Yaqut's account of Ubar. But subtract all the nisnas lore, and what's left is an intriguing geographical description: "Wabar is a vast piece of land, about 300 fer-sakh [37½ miles] wide....The land of Wabar was very much fertile and very rich with water. It was full of trees and fruits. The very fast growing population there could multiply their wealth and could live in excessive luxury.... [There is] a big well called the Well of Wabar."

2

Here we have a thumbnail sketch of Ubar as it really might have been: a sizable oasis watered by a great well, and the home of a rapidly expanding, prosperous population that became a little too full of themselves.

A

S THE TALE OF

U

BAR

was told and retold throughout medieval times, any clues to its underlying reality became more and more submerged in fantasy. This is evident in the variations of the legend that appear in

Alf Laylah wah Layla,

the

Arabian Nights.

The

Arabian Nights

tales have long been considered the product of overheated imagination. When they were popularized in English at the turn of our century, essayist Thomas Carlyle considered them "unwholesome literature" and forbade their presence in his house. "Downright lies," he sniffed. "No sober stone is permitted to kill even the wildest fantasies." Even back in the 900s, historian Abu al-Hasan Ali al-Mas'udi termed the tales "vulgar, insipid"; nevertheless, he wrote of their origin: "The first who composed tales and made books of them were the Persians. The Arabs translated them and the learned took them and embellished them and composed others like them."

1

Still relatively unexplored is a possible

pre

-Persian origin of the tales. Ethnologist Leo Frobenius and mythologist Joseph Campbell both suspected that a number of the tales were in their earliest forms genuinely Arabianâand had their genesis in the valley of the Hadramaut, not far west of our search area.

2

(It was in this valley that Ubar's Prophet Hud was traditionally said to lie buried.) Given this proximityâand given that Iram/Ubar's People of'Ad wander in and out of many of the tales in the

Arabian Nights

âI thought they might conceal a wealth of useful information.

A succinct, relatively restrained tale is "The Story of Many Columned Irani and Abdallah Son of Abi Kilabah." As for clues to Ubar, there is an interesting description of the city's locale as "an uninhabited spot, a vast and fair open plain clear of sand-hills and mountains, with founts flushing..." And, following Ubar's divine demolition, there is the line "Moreover, Allah blotted out the road which led to the city"âa reference, it would appear, to the very road we were seeking.

3

In other

Arabian Nights

tales, the myth of Ubar gathers momentumâand fancyâas it careens from story to story. In "The Eldest Lady's Tale" a medieval traveler enters a version of Ubar and finds it quite intact. It has not been destroyed; rather, its inhabitants "had been translated by the anger of Allah and had become stones ... all were into black stones enstoned: not an inhabited house appeared to the espier, nor a blower of fire. We were awe struck at the sight ... and said 'Doubtless there is some mystery in all this.'"

4

In this version the Iram/Ubar myth has been populated by

maskoot,

an Arabic term for human beings petrified by the wrath of God. It has been suggested that the idea of maskoot came from the discovery by superstitious bedouin of shattered statuary in the deserts of Upper Egypt.