The Republic of Pirates: Being the True and Surprising Story of the Caribbean Pirates and the Man Who Brought Them Down (11 page)

Authors: Colin Woodard

Filled with the treasures of Mexico, Peru, and the Orient, the Atlantic treasure fleets had always offered tempting targets for English buccaneers, privateers, and Royal Navy warships. The Manila galleons were another story. They were built to be impregnable: floating fortresses of 500 to 2,000 tons, bearing hundreds of men and tiers of heavy cannon. Only one Englishman had ever captured one—the buccaneer Thomas Cavendish in 1587—and that had been a relatively small 700-tonner. Dampier himself had attacked a Manila galleon during his last cruise, but, in the words of one of his crewmen, "They were too hard for us." His ship's five-pound cannonballs hardly made a dent in the treasure galleon's tropical hardwood hull, while the Spaniards' twenty-four-pounders smashed into his ship's worm-infested hull. Nonetheless, in the words of another contemporary, Dampier "never gave over the project" and was eager to win young Rogers's support for his plan.

***

Dampier was more desperate to leave England than Rogers could possibly have known. Despite his fame, his career was in shambles. His command of HMS

Roebuck

had been a disaster: The 290-ton frigate sank on the way back to England, and when he and his marooned crew

were finally rescued, Dampier faced three courts-martial. The court fined him his entire pay for the three-year journey, ruling that "Dampier is not a fit person to be employed as commander of any of Her Majesty's Ships." On his Pacific privateering expedition, he quarreled with his officers, lost the respect of his crews and, in battle, hid behind a barricade of beds and blankets he'd built on the quarterdeck. He had failed to adequately clean the hulls of his ships—the 200-ton

St. George

and ninety-ton galley

Cinque Ports

—leaving worms to devour them both. One crewman had even chosen to take his chances on an uninhabited Pacific island rather than continue aboard a decomposing vessel. In the end the worms won and both ships went down, though not before a series of mutinies resulting in most of the crew abandoning their commodore. Dampier somehow made his way home and faced a variety of lawsuits stemming from his poor command performance.

Ignorant of much of this, Woodes Rogers threw himself into Dampier's scheme, a privateering expedition to the Pacific to capture a Manila galleon. The main challenge was fundraising. From Dampier's experience, he knew taking on a Manila galleon would require at least two well-armed frigates with enough men to allow for a sizeable boarding party. Sending these ships to the Pacific would be expensive, far beyond what Rogers could bankroll. They would need an enormous store of food and supplies to sail that far from home, and a team of reliable and experienced officers who could maintain discipline on a journey lasting three or four years. Fortunately for Rogers, his well-connected father-in-law, Sir William Whetstone, had just arrived back in Bristol, and was willing to present the bold plan to the city's leading merchants.

They went for it, hook, line, and sinker. Mayors, former mayors, would-be mayors, sheriffs, town clerks and the head of Bristol's all-powerful Society of Merchant Venturers all bought shares, as did Rogers's friend and possible relative, Francis Rogers. Together these local luminaries agreed to purchase and equip two new frigates already under construction in the dockyards of Bristol.

The

Duke

was the larger of the two, a 350-ton ship with thirty-six guns, the

Dutchess

slightly smaller at 260 tons and twenty-six guns. Rogers invested in the ships and was appointed as both commodore of the expedition and captain of the

Duke.

Another investor, noble-born merchant Stephen Courtney, commanded the

Dutchess.

Dampier was hired as the expedition's indispensable Pacific Ocean pilot. Other officers included Rogers's younger brother, John, and the

Dutchess's

executive officer Edward Cooke, a Bristol merchant captain who had been attacked twice by French ships in the preceding year. One of the largest investors, Dr. Thomas Dover, also came along as the expedition's president, a position that allowed him considerable say over strategic decisions, such as where to sail and what to attack. An Oxford-educated physician, Dover had earned the nickname Dr. Quicksilver for his propensity to administer mercury to his patients to treat a wide range of illnesses. The owners made him chief medical officer and also captain of the marines, with ultimate authority over military operations ashore, which was odd, given that he had neither military experience nor, as subsequent events would show, a knack for leadership.

***

Rogers's expedition would make him famous among his contemporaries, but it has also provided historians with the only detailed account of life aboard an early-eighteenth-century privateering vessel. Both Rogers and Cooke kept detailed, daily diaries of their experiences on the three-year journey and published them as competing books shortly after their return. Together with other letters and documents, they not only afford a comprehensive picture of some of Rogers's formative command challenges, but also a sense of those faced by Thatch, Vane, and other privateersmen during the War of Spanish Succession.

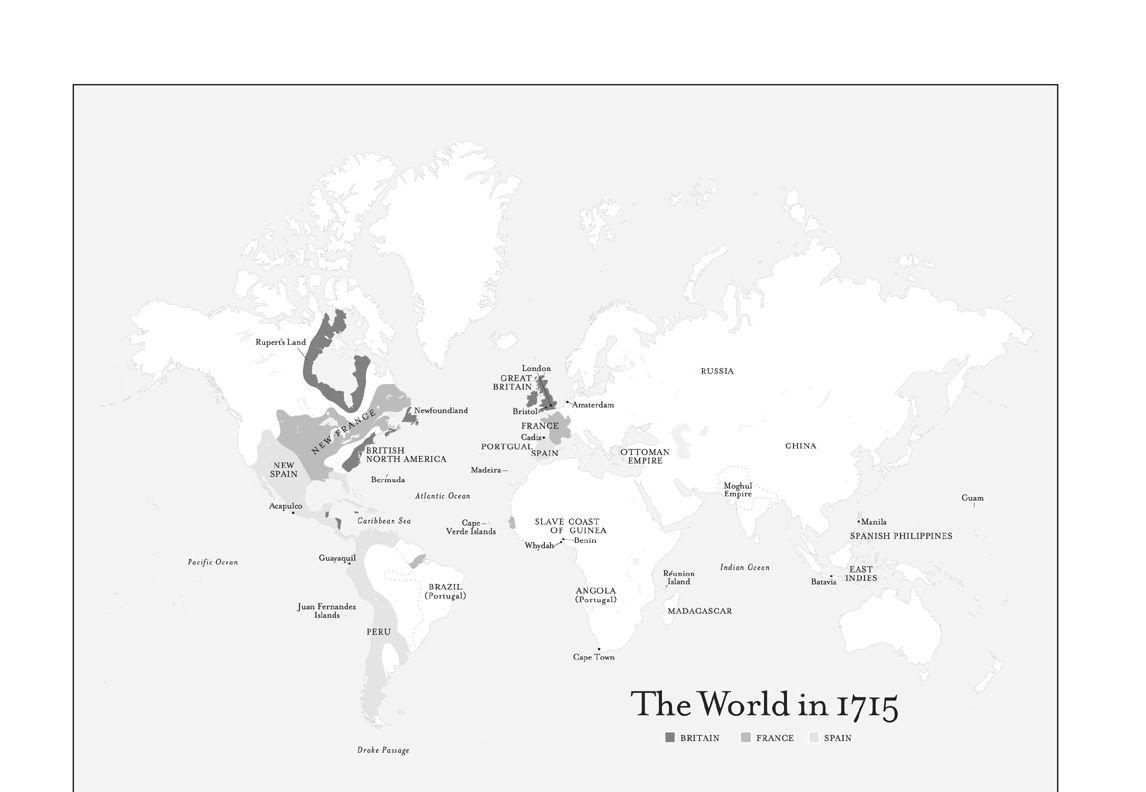

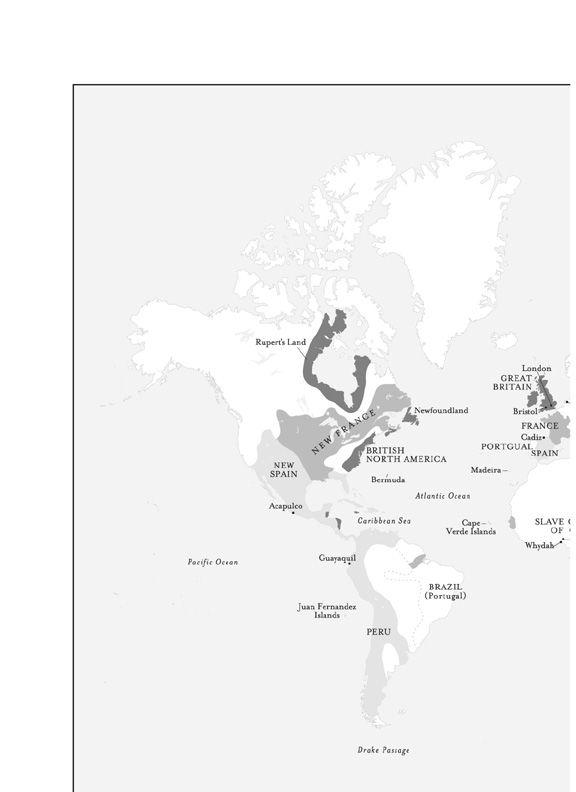

The expedition departed on August 1,1708, the ships flying the new Union Jack ensign of Great Britain, a nation that had been created in 1707 with the union of England and Scotland. Rogers was forced to spend a month in Ireland, retrofitting the ships, stocking supplies, and recruiting crewmen. They left Ireland with a complement of 333, a third of whom were Irish, Danish, Dutch, or other foreigners. The expedition council met soon thereafter to discuss an important problem: a shortage of alcohol and cold-weather clothing for the frigid journey through the Drake Passage. Rogers argued that alcohol was the more important of the two, as "good liquor to sailors is preferable to clothing," so the council resolved to stop at Madeira to stock up on the island's namesake wine.

Along the way, a large number of the

Duke

's crew mutinied after Rogers refused to take a neutral Swedish ship as a prize, a decision that, in their view, deprived them of plunder. The

Duke

's officers broke out muskets and cutlasses and kept control of the quarterdeck throughout the night and, in the morning, managed to seize the ringleaders. Many captains would have executed the mutineers, but Rogers knew terror was not always the best way to win the respect and loyalty of a crew. He had the leading rebels placed into irons and their top instigators "soundly whipped" and sent back to England on a passing ship. The others he let off with light punishments—fines or reduced rations—and returned to duty. He even took the trouble to address the entire crew, explaining why it would be unwise to seize a neutral ship, which would probably result in legal proceedings against them. These actions broke the mutineers' resolve, though the atmosphere on the

Duke

remained tense for many days. Had the ship not had double the ordinary number of officers, Rogers noted in his diary, the mutiny might have succeeded.

***

They spent December 1708 sailing down the Atlantic coast of South America, the weather turning colder as they moved south. Rogers set six tailors to work making the crew cold-weather clothing from blankets, trade cloth, and the officers' hand-me-downs. The winds strengthened as they passed into the latitudes known as the Roaring Forties, and great waves swamped the decks of the smaller

Dutchess.

At times the ships were surrounded by breaching whales or great troops of exuberant dolphins, which, Rogers wrote, "often leaped a good height out of the water, turning their white bellies uppermost." There were large numbers of seals, the occasional penguin, and soaring albatross. By January 5, 1709, the ships had entered the Southern Ocean, and the seas grew to thirty feet or more, lifting the ships so quickly that the men could feel the blood swelling their feet, and then dropping them into the trough so fast they felt almost weightless. As the wind speeds increased, the captains sent men up into the rigging to lower the upper sails and reef the lower ones to prevent them from being torn to shreds. Suddenly there was a terrible mishap aboard the

Dutchess.

As the men lowered the main yard—the crosswise timber suspending the main sail—one side slipped, dropping part of the big sail into the water. At the speed the

Dutchess

was moving, the sail acted like a gigantic anchor, pulling the port side down so far that the frigid gray ocean began pouring onto the main deck. Captain Courtney ordered the other sails loosened. The

Dutchess

swung into the wind, sails flapping like flags, her bow facing into the towering seas. "We expected the ship would sink every moment," Edward Cooke recounted, "floundered with the weight of the water that was in her." The crew secured the main sail; Courtney swung her around, stern to the screaming wind. The vessel began drifting rapidly to the south, toward the still undiscovered continent of Antarctica. Rogers, watching these events from the

Duke,

became increasingly worried as he followed the

Dutchess

further and further toward the bergs and pack ice Dampier had warned lay in these southern waters.

At nine

P

.

M

.

—the spring sun still high above the horizon—the

Dutchess

's exhausted officers went down to the great cabin for dinner. Just before their food was served, a massive wave crashed into her stern, smashing through the windows and carrying everything it picked up, human and otherwise, forward through the ship. Edward Cooke was certain all of them would have drowned in the submerged cabin had its interior wall not been torn down by the force of the wave. An officer's sword was found driven straight through the hammock belonging to Cooke's servant who, fortunately, was not in it at the time. Amazingly, only two men were injured, but the entire middle of the ship was filled with water, soaking every bit of clothing, bedding, and cargo in ice-cold seawater.

Somehow the

Dutchess

stayed afloat through the night, during which time the storm abated. In the morning, Rogers and Dampier rowed over from the

Duke

and found the crew "in a very orderly pickle," busying themselves with pumping water from the hold and lowering some of the heavy cannon into storage to make the ship less top-heavy. Her masts and rigging were covered in wet clothes, bedding, and hammocks hung out to dry in the icy wind. The captains agreed that the two ships had been pushed to nearly sixty-two degrees south (almost to Antarctica), slightly shy of the farthest point south any person had yet been known to travel. By the end of the day, they had swung around to the northwest and beat their way toward the Pacific in the mouth of yet another Drake Passage gale.

As they crawled out of the Antarctic, toward the warmth of the southern spring, the crew began to fall sick. Some suffered from exposure after spending days in soaked or frozen clothing; others were stricken with scurvy, the disease mariners feared more than any other. An affliction caused by a lack of vitamin C, scurvy is thought to have carried off more mariners in the age of sail than all other causes combined. Without vitamin C, the sailors' bodies could no longer maintain connective tissues, causing gums to turn black and spongy, teeth to fall out, and bruises to form beneath scaly skin. Toward the end, as the sailors withered and wheezed in their hammocks, bones broken long before became unhealed and old scars opened into wounds again. Most mariners believed it was caused by exposure to cold and damp clothing, but Rogers and Dover were aware it had more to do with the lack of fresh fruit and vegetables on long ocean passages. At a time when the Royal Navy had no treatment for the disease, Rogers stocked his ships with limes, which were rich in vitamin C. This supply was now exhausted, so the ships were in a race against time to get fresh produce. The first man, John Veal of the

Duke,

died on January 7 and was buried at sea in the Drake Passage.