The Republic of Pirates: Being the True and Surprising Story of the Caribbean Pirates and the Man Who Brought Them Down (9 page)

Authors: Colin Woodard

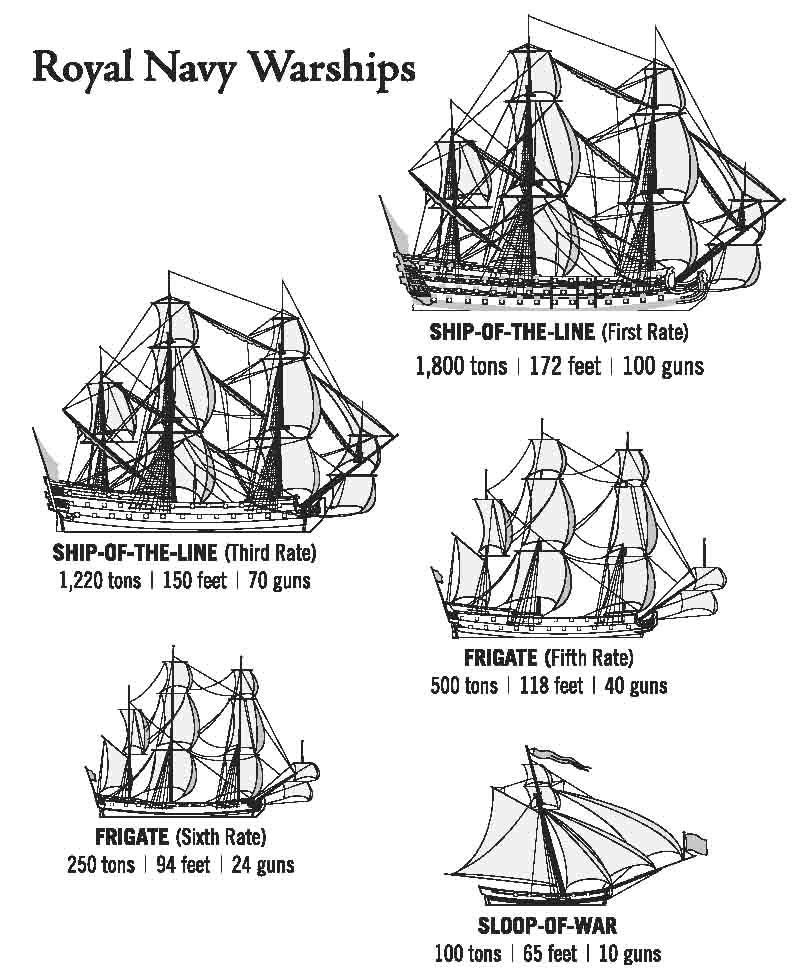

Had the teenage Bellamy been unlucky enough to be grabbed by a press gang, he may well have ended up aboard one of these ships of the line, for they soaked up much of the available manpower. Each of the navy's seven first-rate ships had a crew of 800 men, who were crammed into a 200-foot-long hull with a hundred heavy cannon, and months of supplies and food stores, including live cows, sheep, pigs, goats, and poultry. Bellamy would have awoken in his hammock to the rolling of drums, the cries calling all hands to stations as the massive ship maneuvered into the line of battle, two hundred yards ahead of one ship, two hundred yards behind another. The enemy ships lined up in similar fashion and, after hours or even days of maneuvers, the two lines passed each other, discharging broadsides. The ships would sometimes pass within a few feet, blasting thirty-two-pound cannonballs into each other's hulls. These balls punched straight through people, eviscerating or decapitating, and spraying the cramped gun decks with body parts and wooden splinters. Cannon trained on exposed decks were generally loaded with grapeshot or with a pair of cannonballs chained together, either of which could reduce a crowd of men into a splay of mangled flesh. From the rigging, sharpshooters picked off enemy officers or, if the ships came together, dropped primitive grenades on their opponent's deck. Above and below, every surface was soon covered with blood and body parts, which oozed out of the scuppers and drains when the ship heeled in the wind. "I fancied myself in the infernal regions," a veteran of such a battle recalled, "where every man appeared a devil."

These early engagements took the lives of thousands of men but they were hardly conclusive. Seven English and four French ships of the line fought a six-day battle off Colombia in August 1702, for example, with neither side losing a single ship. Two years later, fifty-three English and Dutch ships of the line squared off with some fifty French vessels off Málaga, Spain, in the largest naval engagement of the war; the daylong bout of fleet-scale carnage ending in a draw.

By happenstance, the Royal Navy wiped out its French and Spanish rivals early in the war. In October 1702, an English battle fleet trapped twelve French ships of the line and most of the Spanish navy in a fjordlike inlet on Spain's northern coast, destroying or capturing all of them. Five years later, an Anglo-Dutch force captured the French port of Toulon and so many men-of-war that the French were unable to engage in further fleet actions. Thereafter on many English ships of the line, crewmen had substantially reduced odds of dying in battle, though disease, accident, and abuse still carried off nearly half the men who enlisted.

Were Bellamy serving in the merchant marine rather than the navy, these early English victories would have made his life a good deal

more

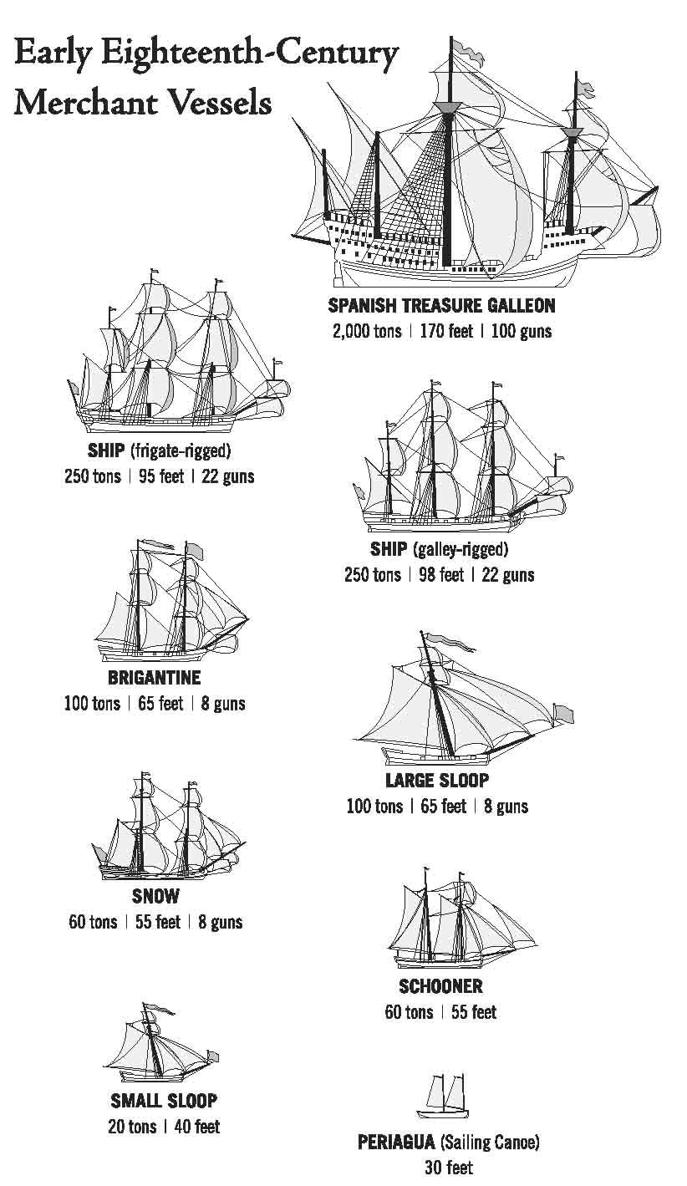

hazardous. After these defeats, the French and Spanish decided to focus their war at sea not on the English navy, but on its merchant vessels, hoping to cut off the island kingdom from its sources of wealth and supplies. The French navy assembled a few squadrons of swift warships for the purpose. However, King Louis XIV decided it would be cheaper to outsource most of the work to the private sector, offering generous subsidies to encourage subjects to build their own privateers. After the Battle of Málaga, the French sent out huge numbers of heavily manned privateers, which typically carried anywhere from ten to forty guns. Over 100 privateers operated out of the French channel port of Dunkirk alone. Together with their counterparts in dozens of other French ports from Calais to Martinique, French privateers took 500 English and Dutch vessels every year; dozens more fell victim to Spanish privateers operating out of Cuba and other parts of the Spanish West Indies. English merchant vessels couldn't leave Dover and other English ports for fear of being captured.

France and Spain were soon to get a taste of their own medicine, and Thatch and Rogers would be among those administering it.

***

At some point before or during the War of Spanish Succession, Edward Thatch made his way to the Americas in search of better fortunes, and on some unidentified vessel he sailed into the capacious harbor of Port Royal, Jamaica.

Jamaica had been an English colony for half a century. Nonetheless, it was about as un-English a place as one could find. The sun was overpowering. Instead of fog and chill, the sea carried in hot, heavy air, smothering its wool-wearing English residents. Thatch found nothing resembling the gently rolling hills of the Avon valley. The ridges of volcanic mountains sliced through their jungled skin, belching steam and sulfur. En route from Europe, the sea had lost its pigment, becoming so clear one could see her sandy, coral-studded footings and colorful inhabitants, even at a depth of a hundred feet or more. There were fish that could fly and birds that could speak. Legions of gigantic turtles crawled from the sea by the thousands, laying piles of eggs, each as big as a grown pheasant. In the fall, storms lashed the island, some so powerful they would flatten towns and leave the beaches littered with broken ships. Sometimes the island itself awoke in an earthquake, shaking off towns, plantations, and people like so many bedbugs. Moreover, Jamaica and her fellow islands welcomed their new residents with invisible contagions: malaria and yellow fever, dysentery, and plague.

To enter the colony's main harbor, Thatch's vessel sailed around a long sandy spit protecting the anchorage's southern approaches. At its tip stood Port Royal, once the largest and wealthiest English settlement in the Americas, whose merchants achieved the "height of splendor" through a brisk trade in sugar and slaves. When Thatch arrived, much of Port Royal was underwater, the result of a devastating earthquake in 1692 that swallowed part of the town and flattened most of the rest, killing at least 2,000 of its 7,000 residents. In 1703, a fire burned what was left to the ground, sparing only the stone forts guarding the harbor entrance and one house, which lay stranded on what was now an island, part of the sand spit having collapsed during the earthquake. A city once known for its splendor and decadence, Port Royal was, by Thatch's time, little more than a slum with "low, little, and irregular" houses and streets that visitors compared unfavorably with those of London's poorest neighborhoods. To make matters worse, Jamaican authorities forced local slaves to carry their chamber pots to a central waste heap located upwind from Port Royal, creating a terrible stench that overpowered residents when the sea breezes kicked up in the afternoon.

Circling Port Royal and its foul-smelling wind, incoming ships crossed Jamaica's busy harbor, passing coastal trading sloops, ocean-going slave ships and naval frigates. Most ships anchored near the north shore, where the survivors of the 1703 fire had founded the new settlement of Kingston at the foot of the Blue Mountains. To the east, a dirt road wound past slaves' hovels and fields of sugarcane in the direction of the settlement of St. Jago de la Vega or Spanish Town, five miles away, which Queen Anne had recently designated as the colony's new capital.

Jamaica had a dubious reputation. After a visit in 1697, the London writer Edward Ward had nothing nice to say about it. "The receptacle of vagabounds, the sanctuary of bankrupts, and a [toilet] stool for the purges of our prisons," he declared. Jamaica was "as sickly as a hospital, as dangerous as the plague, as hot as hell, and as wicked as the Devil." It was "the Dunghill of the Universe" the "shameless Pile of Rubbish ... neglected by [God] when he formed the world into its admirable order." Its people, he harangued, "regard nothing but money, and value not how they get it, there being no other felicity to be enjoyed, but purely riches."

Beyond the docks of Kingston and Port Royal, the island was carved up into huge cattle ranches and sugar plantations, many of them the property of absentee owners who lived in the comparative safety and comfort of England on the profits sent home to them. For decades, English authorities had used the island's plantations as a dumping ground for people they found undesirable: Puritans and other religious deviants, Scottish and Irish nationalists, followers of failed rebellions against the crown, landless peasants, beggars, and large numbers of common criminals all found themselves in bondage to the sugar and cotton planters. Hoards of these indentured servants died, overwhelmed by tropical diseases as they worked the planters' fields under the unrelenting sun; others simply ran off and joined the privateers who used Port Royal as a base to attack Spanish shipping during the wars of the 1660s and 1670s.

In the early 1700s, when Thatch arrived, the plantation owners had given up on indentured servants altogether, replacing them with armies of enslaved Africans brought to the island. Jamaica had already become more than just a society that allowed slavery, it was the slave society perfected. Every year, dozens of ships arrived from West Africa, disgorging thousands of them. Despite the fact that the Africans' mortality rate far exceeded their birth rate, the island's slave population had doubled since 1689, to 55,000, and by the early 1700s, it had exceeded the English population by a ratio of eight to one. Outside of Kingston and Port Royal, Jamaica was a land where a tiny cadre of white planters, supervisors, and servants lived in constant fear of an uprising by the sea of Africans manning their fields, pastures, and sugar works. To maintain order, the English passed draconian slave laws under which masters could discipline their black captives in pretty much any way they wished, though murdering one without cause carried a fine of £25. Slaves could be punished by castration, having their limbs cut off, or being burned alive, punishments that were meted out without a court trial. Any three land-owners could join with two justices of the peace to pass most any sentence they pleased. A resident caught hiding a runaway slave suspected of having committed a crime faced a fine of £100, more than most people earned in four years. Even so, dozens of blacks did escape each year. They established rogue settlements in the mountains, where they grew crops, raised families, practiced their religions, and trained bands of swift and effective jungle warriors to raid the plantations, free slaves, and kill Englishmen. In their capital, Nanny Town, the runaways were said to be led by an ancient and powerful witch, Granny Nanny, who protected her warriors with magical spells.

With the outbreak of war in 1702, Jamaica's plantation owners had to worry about not just a slave rebellion, but an enemy invasion as well. Jamaica was an island in a Spanish sea, located near Spanish Cuba, hundreds of miles from any other English possession. In 1703, French and Spanish forces sacked and destroyed Nassau, Jamaica's nearest English neighbor, obliterating the government and forcing the settlers into the woods. There was good reason to fear Jamaica would be next.

From the Spanish point of view, the English should never have settled in the New World in the first place. Christopher Columbus had "discovered" the Americas for Spain in 1492, although he never set foot on either the North or South American mainland. The year after Columbus's discovery, Pope Alexander VI, acting on God's behalf, had given the entire Western Hemisphere to Spain, even though virtually none of it had been discovered yet. From Newfoundland to the tip of South America, the pope gave it all to Spain, save for the eastern part of what is now Brazil, which he bequeathed to the king of Portugal. Unfortunately, Pope Alexander had granted the king of Spain far more territory than he could possibly manage: sixteen million square miles, an area eighty times the size of Spain itself—two continents already populated by millions of people, some organized into powerful empires. Conquering and colonizing South and Central America during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries stretched Spanish resources to the limit, and the kings of Spain were forced to leave the cold, gold-less forests of the northeastern Americas to the colonists of New England, New Holland, and New France. Everything south of Virginia, however, the Spanish regarded as an integral part of their empire, including Spanish Florida, the Bahamas, and the vast archipelago of the West Indies.